INTRO:

Back in the first decade of the twenty-first century, it was not often that fantasy RPGs veered from the story-telling tropes of heroes with great destinies, damsels in distress and ancient evils awakening. This “remake” of The Bard’s Tale titles of yore does not break the mould, but dirties it with witty cynicism and sarcasm.

The last two bits are perhaps to be expected, because the writers and producers of the game are people that have had much experience with RPG tropes; the most representative of them happen to be none other than Brian Fargo.

Unfortunately, although The Bard’s Tale’s story-writing might have been refreshing to the jaded gamer in 2004 (and perhaps even now), its gameplay is not.

PREMISE:

The protagonist of this game is the unnamed titular Bard. There are no other minstrels to compare him with, but just about everyone would consider him to be quite terrible anyway, no thanks to his terrible reputation, the forging of which he himself is largely responsible for.

Anyway, the Bard is a rather self-centred individual, whose goals in life are professedly “coinage, cleavage and carnage – in that order”. Indeed, the prologue of the game does not make a good first impression of him; he makes use of his magical “talent” to swindle comely women, and he has no issues on resorting to violence.

However, after getting his comeuppance and shortly thereafter the means to overcome that comeuppance, he becomes reluctantly embroiled in an adventure that supposedly promises all three “C’s” – and this despite his suspicion that nothing is as it seems.

CAMERA & MOVEMENT:

The camera is the first thing about the game that the player would encounter, and unfortunately, it is not satisfactory.

The orientation of the camera is almost top-down, and the zoom is not too far out. Consequently, the player can only see about thirty paces ahead of the Bard, which is usually centred in the middle of the screen, even at the maximum zoom level. This distance is not adequate for the purpose of using bows and arrows (which will be described later).

Furthermore, the camera is not very effective at following the Bard. The observant player may notice that its movement is not smooth and is in fact a bit jittery when the player moves the Bard around.

Oddly enough, the camera is a lot more effective during cutscenes, where it so smoothly pans to give the player a good view of what the game wants the player to see. For example, the camera does a good job of showing what the Bard is looking at when he looks at comely female characters.

(Curiously, the camera generally refrains from showing the sky or ceiling. This is probably because the game lacks skyboxes and textures for ceilings, and the developers happen to be aware of that.)

If there is any silver lining to be had from the camera, it is that the player does not need to rotate the camera around too much because there are not many things in the game that would obstruct the player’s view.

By default, the Bard runs to where the player wants him to get to. He does run at a fast clip, if his stride is to be compared with the usual sizes of maps.

If the player has played games where directional inputs result in movements simply in the associated directions with respect to the camera, he/she would be quite familiar with the control scheme in The Bard’s Tale.

MELEE ATTACK COMBOS & BLOCKING:

The Bard, much unlike many other minstrels, is actually skilled at using weapons. This is perhaps to be expected because he does love fighting and killing after all.

However, if the player is thinking that he can just hack away at enemies like the player characters of hack-and-slash RPGs could, the player would be mistaken.

There are inertial delays and recovery times to his melee attack animations. Indeed, working up a combo of slashes takes a surprisingly long time, during which the Bard would be open to attacks. In fact, combos are only ever effective against enemies that are still in their recovery animations.

New players that do not realize this quickly would be tempted to think that The Bard’s Tale has hard combat, but that would not be the case.

More experienced players would eventually learn to block more often, because most enemies would come charging at the Bard with their attack animations already being enacted (there will be more elaboration on this later). A counter-attack shortly afterwards would deal with the enemy, followed by rinsing and repeating.

Of course, the player must watch out for any other enemies, but the Bard can surprisingly block faster than he can attack. Moreover, just about any blocking animation can block incoming attacks in a wide arc, and the time window of the effects of blocking is surprisingly generous.

Anyway, by default, the Bard knows how to use swords. Eventually, he can learn to use more weapons as well as use special attacks, all of which will be described shortly.

(Amusingly, he can use his fists, but this is generally a novelty instead of an effective fighting method.)

MELEE WEAPONS:

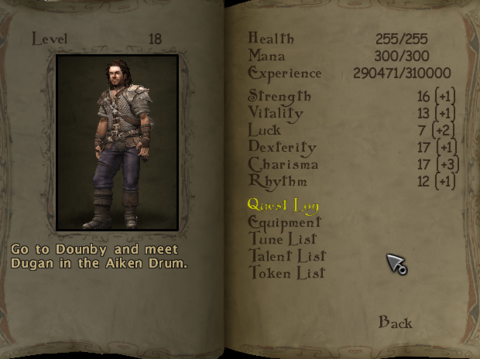

Upon attaining a level of experience, the Bard has an opportunity to pick up new “talents”. Some of these talents enable the use of certain weapons that are more esoteric than just a sword and shield.

There is the Two-Handed Weapon, which cover the use of two-handed swords and axes. These are hefty weapons that have a wide reach and high damage to compensate for their slowness of use.

In fact, it is perhaps more efficient to use two-handed weapons over the sword-and-shield combination. Two-handed weapons block/parry just as well as the sword and shield, and can hit more enemies with their swipes.

Flails are even heftier to use than two-handed weapons, which should be obvious to aficionados of medieval weapons. To compensate for its lack of ease of use, hits from flails cannot be blocked; they simply go through armor-based defences (which generally reduce incoming damage) and are more than likely to knock down the target. Furthermore, the Bard wields the flail with only one hand, while his other hand holds his shield.

Indeed, timing flail swings to hit enemies without having the swinging interrupted is a skill that the player has to develop if he/she wants to use the flail.

BOWS:

The only ranged weapons that the Bard can use are bows. Conveniently, the Bard has an unlimited supply of arrows.

However, the Bard must nock each arrow, which is a process that takes a while and thus which make the Bow quite difficult to use when enemies are all over the Bard.

On the other hand, when the Bard has an arrow fully pulled back, it appears that he cannot be stunned by enemy attacks. Only attacks that can knock him down can interrupt this animation. This is a peculiarity that can be exploited by more experienced players.

Anyway, pulling back an arrow and aiming in a direction causes the camera to shift a bit towards the direction that the Bard is aiming at. This does increase the view distance between the Bard and his target, but this is still a deficient solution for addressing the issue with the camera that has been mentioned earlier. Fortunately, there is an exploit that overcomes this inadequacy.

Arrows can actually travel further than just the immediate screen. This is not told to the player, but more observant players would eventually learn this and exploit to hit enemies that are not within the player’s sight but are visible on the auto-map.

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

Some time into the game, the player can have the Bard picking up Talents that allow him to perform special attacks with specific weapons, if he has already learned to use them. Many of these special attacks are quite easy to pull off, though the player must know how to time them.

For example, the Shield Bash ability is automatically triggered if the player successfully blocks an incoming attack with a shield. The shield bash conveniently stuns any adjacent enemy in a wide arc around the Bard.

Some special attack talents are very much a must-have, due to their convenient designs. For example, the Heavy Parry talent that comes after Two-Handed Weapons grants the Bard a modified parry animation that is followed quickly by a wide swipe that hits many enemies around him. He also appears to be mostly invulnerable during this animation, because the game considers that he is still deflecting attacks. The same can also be said about the Riposte talent that comes after Dual-Wielding.

Another example of a must-have talent is any of the special attacks for bows. These simply increase the firepower potential of the bow. On the other hand, these special attacks require more time to prepare.

TUNES:

One of the main draws of the game is also one of its most disappointing. Although the tunes in the game are pleasant to listen to, they have very limited involvement in gameplay.

In the Bard’s world, music is another way to work magic. Since the Bard does happen to be a musician, he does have the ability to work magic.

However, the only magic that he can use is apparently the magic to summon individuals from across the world without their consent and bind them to his will.

There is no other form of music-based magic, which is perhaps a lost opportunity for more sophistication in the gameplay.

MINIONS:

As mentioned earlier, the Bard’s musical magic involves the summoning of minions. It is not entirely clear how the Bard’s magic can summon them and why certain tunes are associated with specific individuals.

Regardless, once they have been summoned, they follow him about as loyal companions, though calling them “loyal” would be a stretch (as will be elaborated later).

At first, the player starts with a rat, which is next to useless in actual gameplay. However, it is used for a running gag in the story, specifically the Bard’s tendency to swindle people by summoning the rat to spook them and then dispelling it.

Eventually, the player gains more powerful minions, such as the interestingly-named “Thunder Spider”, which is really a ball of lightning with electrical arcs shooting out of it like they are actual limbs.

Anyway, each type of minion has its own idiosyncrasies. For example, the aforementioned Thunder Spider appears to have a charge meter of sorts; once battle commences, it can release a considerable barrage of lightning arcs. However, once it runs dry, it is left defenceless for a while as it recharges.

Which minions to use is generally a matter of preference and expedience, but there are a few that seem quite useless in combat. This is mainly due to their deficient A.I. scripts, which prevent them from making use of their capabilities properly.

For example, the Elemental minion is a fiery creature that can cause the ground in a few paces around it to burn. This burning ground is ostensibly to be used against enemies that try to surround the Elemental, but the Elemental does not know when it is most optimal to release its burst of fire. It may well release its burst of fire, after which it moves away and thus luring its target away from its fire. Considering that the Elemental’s attack takes a while to recharge and it has no other form of attack, the Elemental is practically defenceless after it has attacked.

Some other minions are not intended to be use for combat. Instead, they are utility minions or minions that are directly intended to keep the Bard alive as long as possible.

For example, there is a Light “Fairy” that the player would find later in the game (and whose voice-over the player would find terribly surprising). The minion is a flying creature that is also a light source. It also happens to illuminate dark areas. (Alternatively, the player could turn up the brightness, which increases the gamma rating of objects.)

Another (more useful) example is the Explorer, who is a spry old man that has an unhealthy fixation on physically stopping deadly traps from springing. Of course, he invariably fails in stopping them and gets hurt, but for whatever reason, his intervention prevents traps that usually reset from resetting ever again.

MINION UPGRADES:

The minions start out with their own special abilities already, but each can be upgraded once to improve its statistics, as well as unlock new capabilities.

For example, the aforementioned Explorer gains the ability to spot hidden doors upon being upgraded. Another example is the Crone obtaining enhanced healing spells, as well as the ability to hex enemies that attack her.

However, upgraded minions cost a lot more mana to summon (and thus replace when they are slain). Considering this, it would have been more convenient if the player had been given the option to summon un-upgraded versions of minions.

INVENTORY & GEAR:

Being an adventurer, the Bard does gather loot and gear to kit himself out while lining his pockets too.

If there is anything that The Bard’s Tale does differently from so many other games, it is that it does away with the selling of vendor trash.

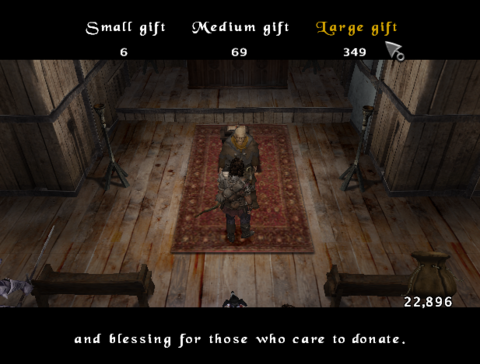

Indeed, any strange thingamabob or underpowered gear that the player obtains is immediately converted into silver coins (the currency in the game). This requires the player to suspend his/her sense of disbelief, but it is very convenient from the perspective of gameplay.

Amusingly, the game will provide a zoomed-in view of the item on the right side of the screen. Most of these items have been seen as vendor trash in typical fantasy RPG titles before, such as wolf pelts, but some others are very oddball, such as snow-globes and family photos.

Unfortunately, the inventory system that the player uses is not as interesting. In fact, it is a mere list of objects. The player will not need a user interface with any more sophistication than this, because of reasons that will be described shortly.

The acquisition and utilization of gear are uninspired. The player starts with some meek weapons and armour, but can obtain new ones that are straight upgrades. These later gear pieces simply replace the older ones.

There are no special gear pieces with special properties. Even if there seem to be any, their properties are mainly cosmetic, such as the Ego Sword and Shadow Axe.

Indeed, if the player is hoping for more versatility in the Bard’s gear, he/she would be disappointed.

TOKENS:

The game tries to include the trope of magical trinkets, e.g. rings and necklaces, in a different way compared to other fantasy RPGs. However, though it is indeed different in its implementation, it is a straight-forward and dull one.

Throughout the game, the player may obtain objects that increase the player character’s statistics; the game will loudly announce them with close-up views of the items that hog the centre of the screen for a couple of seconds.

The player cannot see these objects on the player character’s model, but their effects are there. However, the game does not inform the player that for tokens that increase the same statistic, the token with the strongest magnitude in its offered increase supersedes the rest. In other words, their effects do not stack.

This makes lesser tokens useless and obsolete when the player finds better ones. The obsolete tokens cannot be sold off, so they uselessly remain in the player’s inventory.

If there is any saving grace to be had with the system of tokens, it is that the narrator has some witty remarks in addition to the official lines about tokens.

MAGIC STONES:

In addition to the musical magic that the Bard can utilize, he will come across “Spirit Stones” that allow him to summon the essence of certain characters with considerable magical power. Different stones grant different powers.

For example, the stone of Caleigh grants healing in a massive radius. In contrast, the stone of Herne is an offensive stone, albeit one that applies crowd-control de-buffs and damage-over-time (to use some action-RPG terms).

The use of these stones does not draw power from the Bard’s reserve of mana. Instead, and perhaps in a good design decision on the part of the developers, they consume what the game refers to as “adderstones” (or more correctly, “adder stones”, which are items associated with folklore in the real world).

With that said, the adderstones in The Bard’s Tale look nothing like the real-world ones. In-game, they are spiky purple and magenta crystals.

Anyway, adderstones are in limited supply. They can only be found as loot from treasure chests and as rewards from certain quests. Spendthrift players who rely on them too much to get through fights would learn about this scarcity the hard way.

Still, players who are careful will find that they will always have enough adderstones for particularly difficult fights.

Interestingly, the player can spend more than one adderstone on any magic stone for greater – and some times different – effects. For example, spending more than one adderstone on the Caleigh Stone grants defensive buffs in addition to healing. Knowing how many to use is important, so it is fortunate that the game does pause time while the player deliberates on a decision.

(The animation for using a stone also conveniently renders the Bard invincible too.)

What the game does not inform the player about is that as long as the temporary effects of a stone remains in play, the player is barred from using another stone or the same stone. This makes higher-level use of stones a bit risky (with the exception of Caleigh’s stone, which is practically the most useful of the three).

ENEMIES:

The enemies in the game would have been interesting, if not for the game’s indecision on whether it wants to be a hack-and-slash RPG or a more sophisticated one.

The enemies in the game are mostly cookie-cutter archetypes, such as bruisers or grunts that come forward to deliver beatings, healers that hang back to heal, chargers that give tells on their charging attacks and archers that lay down fire. There are few enemies that diverge from such tried-and-true – and boring – archetypes.

Granted, hack-and-slash RPGs have done such enemy designs before and they get away from such complaints. However, they have a good excuse in the form of looting systems that make grinding through masses of typical enemies still enjoyable. The Bard’s Tale has no such excuse, due to the simplified looting and inventory systems that have been described earlier.

If there is any sophistication to be seen in the gameplay designs of enemies, it is in their animations.

As mentioned earlier, enemies can start their attack animations even while they are moving towards the Bard. This is because the game can animate their lower and upper bodies separately; the same cannot be said about the Bard, which cannot run and make attack animations at the same time.

At first, this may seem to make the enemies in The Bard’s Tale seem more challenging than those found in so many other games, in that they do not need to be standing still to start performing attacks. However, eventually, the determined player would learn to counter them by blocking, and then attacking afterwards. This tactic generally works against just about any enemy.

Almost all enemies can be knocked down, meaning that the flail can be a handy weapon against enemies with long attack animations. However, there are few of these enemies, and knock-downs with any other weapons are a matter of luck.

At least there may be some entertainment to be had from the character designs of these enemies, as will be mentioned later.

CHARACTER DESIGNS – OVERVIEW:

For better or worse, most of the appeal of The Bard’s Tale lies in the characters in the game and not its gameplay. If the player can swallow the “safe” and dull gameplay, he/she is rewarded once in a while with the wit that is shown by the characters.

NARRATOR:

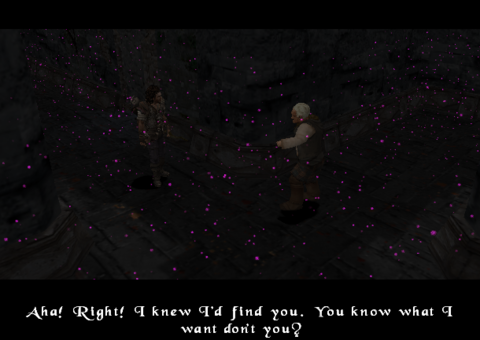

The Narrator, voiced by the very talented (and sadly, departed) Tony Jay, is the first character that the player would encounter. Far from being a person that is removed from the story, he is actually somehow associated with the Bard, albeit this association is one of mutual loathing.

Certainly, it does seem like he is reluctant in telling the tale of the Bard, to whom he expresses a lot of snide sarcasm at, if he is not insulting him outright. (One of the variations of his voice-overs for the loading screen has him calling the Bard an “ass”.)

Tony Jay did a splendid job of delivering such expressions, as to be expected of a veteran voice-actor.

Interestingly, the Narrator is also depicted as a voice in the head of the Bard, who appears to be the only one who can hear him and respond – much to the bewilderment of people around the Bard. Such moments make for surreal breaking of the fourth wall. This plot point will not be developed further though.

THE PROTAGONIST:

The protagonist is quite the snide and confident egotist, if the cover art of the game that has him smiling wryly does not suggest so already.

Interestingly, Cary Elwes, who is a voice-actor with a low profile but a vast portfolio of many voice-acting projects, provides the voice for the Bard. Before the Bard’s Tale debuted in 2004, he was already a veteran in voice-acting. Thus, he delivers a performance that fits with the Bard’s intended personality.

However, it has to be mentioned here that the Bard’s personality designs might have been too far ahead of its time. In 2004, his cynical and snarky demeanour certainly had him standing out among milder-mannered video game protagonists – and not necessarily for the better. Only the most jaded of gamers back then would be able to appreciate his sarcastic wit and his sometimes pompous behaviour.

Of course, tolerances have changed in the years since.

Interestingly, the player is given binary choices when regarding what response the Bard would give to an NPC. These choices are depicted with two masks, one grinning and the other frowning. The astute player would notice that more often than not, neither choice is very different in spirit from the other.

The smiling mask suggests that the Bard would be polite or nice to the NPC, but the remark that ensues is generally at best delivered with blandness that suggests hollow insincerity. At other times, the remark is a backhanded compliment.

The frowning mask has the Bard acting more in character though. The Bard’s remarks are convincingly sarcastic, cynical and sometimes outright rude to the NPC that he is addressing. Sometimes, he just threatens an NPC with bodily harm.

When the Bard is in control of his own words, he is often grumbling over having to do pedantic quests and such other hackneyed chores. Although this may bring a smile to a jaded player, it is also a stark reminder that the player has to suffer such gameplay tropes anyway.

MINION BEHAVIOR:

The weak chinks in the designs of the characters in the game mostly lie with the minions that the Bard can summon. That is not to say that they are terribly insufferable or are boring – far from that. It is that there are so many lost opportunities to flesh them out.

As mentioned earlier, some minions are extra-dimensional creatures with little sentience, such as the Thunder Spider and Elemental, but most of them appear to be individuals that have been summoned to where the Bard is.

For example, the Brute’s exclamation of “where am I?” when he is summoned strongly suggests that the minions are just people that are going about their own lives when they were summoned, likely against their will.

Some of them even seem aware of the Bard’s identity, namely the Explorer and the Mercenary who refer to him by his name (if “Bard” is his name, of course).

Such impressions would not be developed further, unfortunately. This is a shame as well as a lost opportunity, because each of them appears to have a personality that is very different from the others’.

There are, however, “easter eggs” to be had from them. If the player happens to be lucky enough to have the right minions available at the right moment and right time, they may make remarks that would be otherwise unheard. These remarks tend to be references to the game’s sources of inspiration though, so their significance would only be apparent to those who do research on them.

NPC – CHARACTER DESIGNS:

There are a slew of NPCs in the game with different personalities, though such differences are not immediately clear because most of them share the same model shapes and thus look little different from each other. However, they are a lot easier to appreciate (or loathe) when they start talking.

Unfortunately, they have very stereotypical Irish and Scottish accents. It can be difficult for players that are not used to such hackneyed fake accents to listen to them, which, if such is the case, does not make a good first impression of them and the game’s designers.

Nevertheless, if the player can stomach their voices, they have a lot of entertaining things to say, and the Bard has a lot of entertaining replies in turn.

For example, there is a certain NPC that will hound the Bard about a petty matter for quite a while. The player can have the Bard caving in early to stop such nuisance, or be entertained by the Bard’s particularly caustic remarks at such an annoyance.

An important aspect that NPCs pose in the gameplay of The Bard’s Tale is that the Bard’s responses to some of them may determine what benefits that he obtains. This had been touted in the marketing of the game, but these are really simple binary choices. For certain NPCs, there may be more than one chance to know which response is more suitable, but that is just about the only additional permutation in the choices.

More experienced players would just replay these scenarios to know which choice to make, but the lack of a convenient game-saving feature hinders this. (The game uses static save-points.)

SHOPKEEPER & BARTENDER PERSONALITIES:

The player will be frequently browsing shops and bars for the benefits that they can provide, so it is fortunate that all of these characters are fully voiced.

Indeed, they provide amusing descriptions of the categories of objects that they sell, in addition to descriptions of individual items. Moreover, they even have unique lines that conclude the sale of any particular item. This is voice-over work that is very rare in video games, both during the game’s time (2004) and the present (2014).

For example, there is a supposedly insane shopkeeper that makes a lot of frenzied gestures as he talks (or rather, gibbers). Yet, he retains enough of his salesperson skills that the observant player may not be entirely convinced that he indeed is crazy.

However, some of the things that certain shopkeepers say may suggest that much of the literary research that the game’s designers have done have been invested in the dialogue lines instead of the gameplay.

For example, there is Seamus, who is a blacksmith that is well-versed in weapon- and armor-crafting as well as selling them. He says many impressive things about weaponcraft in an amusingly bland but smooth voice. Unfortunately, all that research that went into weaponcraft and medieval combat did not translate into actual crafting mini-games or particularly sophisticated in-game combat.

Bartenders are just as chatty as shopkeepers, if the player deigns to have the Bard inebriated and thus “benefiting” from the effects of liquor (which are clearly stated). Most of them share the same model and sometimes even the same voice talents; the only (very obvious) exception is the first bartender that the player encounters.

ENEMIES – CHARACTER DESIGNS:

It has been mentioned earlier that most enemies in the game fulfill archetypes that had been seen in so many other fantasy RPG titles before. Fortunately though, their personalities – if they are sentient enough to have any - compensate for the bland combat experience that they pose. More importantly, instead of just fighting them outright at once, the Bard sometimes engage in witty conversations with them – before fighting them outright.

Early examples include the “Kunal Trow” – which are really only The Bard’s Tale’s take on the archetype of savage greenskin goblins. However, the loot that they drop, which include family photos and fancy pants of all things, suggest humorous things about them.

The most interesting examples though are the undead. Although the undead that the player would fight do very much behave like undead in so many other fantasy RPGs, what they do in their spare time is hilarious.

There may be some problems to be had in the designs of the personalities of enemies though. The Vikings and their undead counterparts are the most prominent examples.

Firstly, the Vikings have very stereotypical Swedish (or possibly Norwegian) accents, which the Bard himself will lampoon at one point in the game. Perhaps more jaded players can stomach this, but this moment – and another one in which the Bard lampoons a fictional Scottish dialect - can seem offensive to players with thinner skin.

Speaking of the Vikings, their undead version, the Draugrs (undead warrior wights), happen to use the same voice-overs as their living Viking kin during battle. That they sound differently during in-game cutscenes may seem to be too much of a contrast.

OTHER MENTIONS ON WRITING:

The game may make some statements that may not go down well with the politically correct. The Bard himself has more than one bawdy pick-up line for just about any comely woman that he comes across. There are also more than a few characters that perpetuate gender and body-size stereotypes.

Of course, if the player can stomach all these hackneyed writing, he/she would be rewarded with witty remarks from the Bard, the Narrator or sometimes even the summoned characters.

Most of these remarks concern pokes at fantasy RPG tropes. There are even pokes at relatively rarely seen tropes, such as talking walls and doors that speak cryptic warnings. For these particular pokes, the sentient walls and doors tend to have a few proverbial screws loose, which is a problem that they will humorously blame on being stuck where they are for aeons.

However, these attempts to lampoon tropes in quest designs of RPGs may seem to just perpetuate the tropes instead of turning them on their heads. For example, there is a side quest that has the Bard going about trying to find items for a pair of suspicious-looking persons (with terrible fake French accents). This quest may seem to be the game’s take on fetch quests, but like these, it is a hassle.

LEVEL DESIGNS:

Whatever place that the Bard would go to is effectively a dungeon. This also applies to areas that are supposedly outdoors; curiously sturdy stone walls line the boundaries of these maps, if the game does not resort to more convincing obstacles such as cliffs.

Just about every dungeon that the player would trudge through is tepidly linear. At the very least, some dungeons do attempt to give more than one route, if only to accommodate different playstyles for the impatient. For more thorough players, they may well backtrack in order to clear any remaining enemies and snag any treasure that has been left behind, but they will discover that the other routes are just as dull anyway.

The game developers even seem to be aware of their tepid dungeon designs. The Bard makes snide remarks on these, such as levers for locked gates well within reach. Although these are hilarious as intended, they are also reminders on how irrevocably predictable the level designs are.

The dungeons do have some good aesthetic assets (which will be described further later) and initially interesting attractions, but they repeat these so many times that their appeal would dry out quickly. Chief of these is the Metal Wall Mouth character, which at first is humorous but eventually becomes easier to ignore over time because the game recycles its lines many times.

There are some attempts on the developers’ part to sometimes make the gameplay different from the usual, but these can seem contrived to the jaded player.

For example, there are places where purple magical particles hang in the air; having the Bard move into them causes any summoned minions to be immediately killed. This means that the player has to make do without minions, but this would not make the gameplay feel any refreshing; it can be construed as just a cheap increase in difficulty.

Then, there are levels that require the player to escort NPCs. These levels reveal the uneven efforts that the developers have invested in designing the levels.

Generally, the maps that are seen in the game have very straight and angular boundaries, with few round shapes and arcs to be seen in their boundaries. NPCs, and minions, with their very basic path-finding scripts, would ostensibly have no issues navigating such boring environmental boundaries.

Yet, some developers that have reviewed the maps have decided that the levels should look more sophisticated, so they have added in objects such as rocks and tree stumps (this is not an exhaustive listing). These objects can confuse NPCs and minions quite easily, causing them to be left behind.

The game developers’ solution for this is to immediately despawn them and respawn them just outside the edges of the player’s screen; this can be observed from looking at the mini-map. This suggests that the game developers are aware of the limitations of the camera and instead of addressing it, they had exploited them for a cheap fix to another problem.

If not for the hilarious songs and conversations to be had from the characters in the game, trudging through the boring levels would have been unrewarding. (The game developers may even be aware of this too, for there is one level that is named “Obligatory Lava Level”.)

VISUAL DESIGNS:

InXile Entertainment, which is the developer of the game, had not been sitting on its backside ever since producing this game back in 2004. However, that is not to say that they had been supporting the original packages of the game; they had been updating the game and repackaging them for different platforms and online distributors instead.

These later builds of the game benefited from the implementation of water physics such as ripples across surfaces, finer textures, more dynamic shadows and of course more colors, than there were, if any, in the original 2004 build of the game.

Unfortunately, players that are computer-centric may be disappointed about the current build of the game. The most apparent cause for disappointment is that the game is irrevocably stuck at a resolution of 640 by 480 pixels, and unceremoniously stretches itself across wide-screen monitors.

Furthermore, the Mac version of the game has commands that the Windows version lacks, which may give the impression that there had been uneven attention that has been given to the post-launch development of the game.

The game developers have tried to include some interesting art assets, such as eerie glowing runes at the bottom of walls (which is an odd place to have them), flapping cobwebs and swaying grass blades.

Unfortunately, missteps on their part make these assets difficult to appreciate. For example, although it may be entertaining to watch certain towers degenerate very quickly after their masters have fallen, being forced to backtrack through them while fighting angry cultists can seem like a slog.

Then, there is the issue of recycling the same assets for many maps, which have been mentioned earlier.

If there is anything visually interesting in the game to be seen by the jaded gamer, these are the animations for the more hilarious of the in-game cutscenes.

SOUND DESIGNS:

The Bard’s Tale has the usual sound effects for metal-clashing and enactment of magic. There would be nothing that the player who is experienced in fantasy RPGs has not heard before.

If there is anything refreshing to be heard, they are the tunes that the Bard plays whenever he summons or dismisses minions. Each type of minion has its own tune, and upgraded versions have sounds from instruments that the Bard does not have added onto them.

Speaking of instruments, the type of instrument that the Bard has will determine the quality of the tunes. For example, he may be using a lute, and the tunes would sound like they have been played using a lute. If he has a flute instead, the pitch of the tunes would be matching.

Furthermore, having certain weapons out replaces the instrumental tunes with something else. For example, having the Shadow Axe out has the Bard playing a bass guitar version of the tunes. It is uncharacteristic and thematically mismatching, but it is an amusing difference nonetheless.

As mentioned earlier, the voice-overs have plenty of hackneyed fake accents. That is not to say that the voice-overs are boring and bland though – far from that. Despite having to force fake accents, the voice talents that contributed to the game have performed their lines with convincing emotional inflections. The Bard is arguably the best voiced, if one has no issue with his snide apathy and snarky confidence.

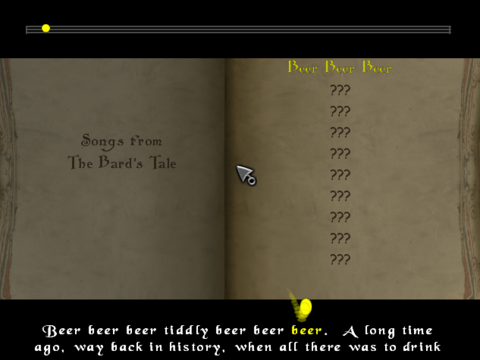

The silly songs in the game are one of its main draws. Some of them appear to be variations of songs that are sung in the real world, such as a certain song about beer that is supposedly associated with the Gaelic peoples. Most of them though, are pokes at the Bard’s exploits.

However, the songs have not been recorded such that they match the ambiance of the level that they are encountered in. For example, many of the “Bad Luck” songs have reverb from the recording room.

Despite the prevalence of the songs and musical tunes for the summoning feature, the game, oddly enough, lacks any background music.

CONCLUSION:

It cannot be denied that a lot of effort had gone into the development of The Bard’s Tale, but it had been invested in its songs, voice-overs and writing instead of its most important component, its gameplay. The game itself is aware of the tropes in its gameplay, but instead of addressing them such that they seem more refreshing, it took the opportunity to lampoon them instead while still having the player trudge through them. Such caveats prevent The Bard’s Tale from being as refreshing as it was touted to be.