How a game like this operates, it is interesting to notice how it happens as you play: opening on a ship carried over from the earlier game, the main character is just 'someone new' - not an a priori Great Character, or Great Person if you will, but an 'Exile', intentionally nobody and driven out of the game's world and then returning, probably a trenchant parallel to the player of KOTOR him- or herself. This is only my first review, or my third or something, its difficult to write sensibly and give substance to a game like this; my review will probably reflect, in many ways, only the fragmentary nature of this game and the way I experienced it, although it will probably also reflect the fragmentary state of my mind right now.

Somehow I feel like playing it again, but I do not think it would be right, so instead I will be writing this short reflection on it, this feeble gaming application, thriving, somewhat familiar, yet an interesting little program.Especially memorable was the moment when I refused to give money to a beggar in Nar Shaddaa, one of the many scripted moral decisions that everybody gets when they play through the story, the story is non-linear in its free choice of which planet you will go to next with the Ebon Hawk, on which you travel, on which your party socializes with you: a burly bunch, they just stand around there. It is a little disconcerting, a little confusing: who are they? They seem to know you: if you are evil your body deteriorates superficially, like a tired person you start to appear tired, as the dark side sinks it claws into you; and your party tells you how tired you look. And then you veer to the light side, tirelessly, and your friend tells you the way you seem more at ease with yourself, probably because your lighter conscience allows you, enables you to sleep more peacefully. No one ever slept peacefully after plundering cities, after hearing how the fate of a people rests on their shoulder, a little surrealistic all of it. It is something somewhat missing from computer games in general: realism. Believability. Animal superficiality or something, something that helps you connect to the simulated people. This is not a manifesto, I just want to say that time and time again I think about that scene with the beggar and when I am tired and look at my dried out skin I think of the Dark Side. Imagining myself standing in the plundered, ruinous valley of the Sith Lords on Korriban, and then remembering the ghost arising because the bodies were disturbed: how all these things consistently occur. Baffling. And when you finish the story, you can play through all of it again and again, ad infinitum, ad fundum,

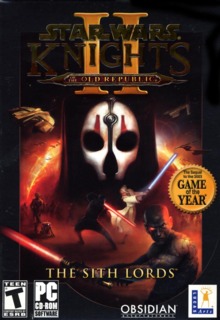

In the title I called this game 'practical'. This it carries over from literature itself. It is a well-written game, good voice-actors, good dialogue options - that sounds dumb - dialogue options are very important, but they are not as central and meaningful as they are in fully text-based games; for games like KOTOR 2 mobilise language, but indirectly; for the world itself is driven by something else entirely, seemingly, you progress only through the scripted nature of the world around you, which does not adhere to laws but only to a fascinatingly code-narrated reality independent from the soulful, lingual reality that it cross-genres into its own system: nothing about it is a given, obviously, for, as I said, as I am trying to express (what is there to be said?) the way this game will haunt me forever, and might haunt you too as well, I look for a acceptable way of expressing the conditions that make this game important, in the oblique, ubiquitous sense as they are inherently supplied through the game's superficial construction. Mechanically, this game is solid gold. Solid interactivity. Turn-based combat systematics. Or, alternatively, its a life-time combat system, character-building, a carry-over (I am sorry, I am getting ahead of myself here) non-adaptability routine - as in, unless you save and reload, the game-world stabilizes immediately as you progress and make decisions -, by which I mean that its fun sometimes, of course, that the system in front of you as you battle is consistently and organically applied by your symbiotic, role-playing choice-relations with the character, the hero you have created and whose life you try to personalise and enact (otherwise you would be playing a shooter, obviously, or a strategy game), this character that carries over from battle to battle (because it is the apparently-continuous-story style of campaign coding that would seem to be in use in this game) makes battles both more personal and yet at the same time less meaningful, because these kind of games totter at the brink of the somehow digitally real and the somehow humanly, understandably real.

For the purposes of these player-based, and quite uninformed, unprepared reflections, unpolished as they are, but its enough, it is sufficient for now, for all that I right now want to say, in these unprepared reservations, is that I like the game as a Star Wars game, but I am also sorry about its nature as a Star Wars game. As Plinkett said, the American films by Lucas et al. are quite unconnected from all this extended lore and all this sprawling digital experiential infrastructure created for the purposes of the amusement of those of us who have the patience or lack of patience to extend our interests in this weird Sci-Fi space opera theme and schema to alternate media such as games and books, and perhaps a few chosen ones among us even fan-based pictures and what not: this is not what a game should be. For all it is worth, I believe this game fails in the final analysis in its so called ethical components by not reflecting due-fully on its Star Wars inheritance and the way its legacy will be over-determined by the presence and role-play re-enactment of future and present films of said series on all the future remembrance of the games lamentations on such worldly and less-than-worldly incidental and existential problems. War in this game does not automatically engage the player in the fictional staging of the theatrical-developmental processes that underlie its prescience distinctions, not only of right and wrong, but of the essence of social and economic relations: the non-presence of a meaningful contentious and dromedary credit and species flow, both biological, mechanical and financial, deserve our critical appraisal.

Once again, I cannot promise the usefulness of these unpolished reflections, but I will say that the good parts of this game can only be appreciated by preparing beforehand a mental-set more or less cold and unresponsive to the fictional element of this game, which cannot be seriously apprehended because of its unrecognised cultural descending along the axis of gaming proper. Because of this, and exclusively because of this, I recommend any player to approach this game not as a theory of life, but as a series of events turning on, what I called earlier, your character's carry-over non-adaptability routine, not as a model of careering or improvement, but as a natural history of the ideology of contention: only by focusing the game's modelling on a simple unit, say, political agency in a sleepy specimen of our Dutch population (that's me) can the game truly have merit. Hopefully this review has been able to reflect that these merits, when probably approached, can indeed be profoundly regarded despite the interpretative challenges it raises through it's mild but relatively, I would not say absolutely, but mildly and occasionally aggravating complexities.