The third iteration of the Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell stealth action franchise features the continuing adventures of Sam Fisher, a top secret agent who's sent in to accomplish the US government's dirty work when political situations go sour. It's also got a brand-new two-player cooperative mode in which a pair of spies work their way through dangerous assignments. The GameCube version of the game is sadly missing the innovative four-player competitive mode featured in Chaos Theory (and its predecessor) for the PC, Xbox, and PlayStation 2. And while that's the biggest omission, unfortunately it's just one of the numerous corners that have been cut to make Chaos Theory for the GameCube a mockery of its PC and Xbox counterparts. It's mostly similar to the half-baked PS2 version, but with no versus mode, clunkier controls, a useless Game Boy Advance connectivity feature, and a bunch of GameCube-exclusive glitches. Strictly on its own merits, this version is an altogether unimpressive action adventure that still smacks of being a watered-down port of a technically superior game. In other words, both GameCube owners and Splinter Cell fans deserve better than this. It'd be very difficult to understand what anyone sees in the Splinter Cell series solely judging by this version of the game.

Though the cooperative campaign is the most original aspect of Chaos Theory, the solo campaign is the highlight. It's once again composed of a linear series of missions, but these are generally somewhat bigger, more open-ended, and more fun than those of the previous games. Set in the near future, the campaign focuses on the threat of informational warfare and a tenuous relationship between the United States, North Korea, and Japan. Enter Sam Fisher, who's summoned to various international hot spots to find the truth, and possibly to silence certain dangerous individuals. You'll control him from a third-person perspective as he infiltrates enemy compounds and ventilates his foes.

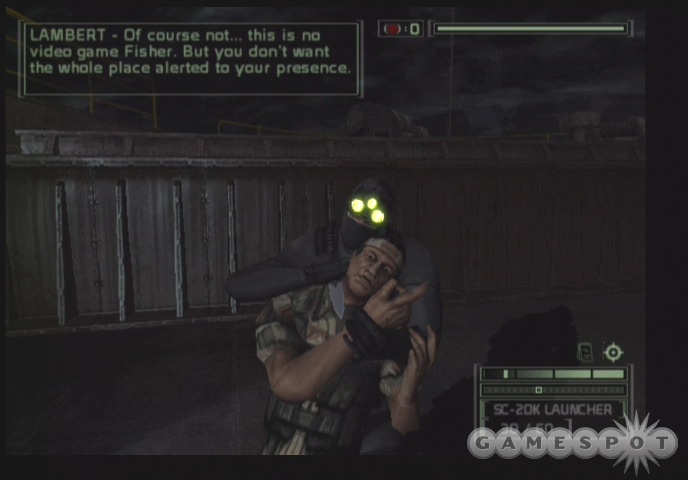

The story is a techno-thriller that lives up to the Tom Clancy name, but storytelling has never been Splinter Cell's strong suit, and Chaos Theory is no exception. Some unfocused between-mission cutscenes sometimes set the stage for your next assignment, but a lot of your mission details are conveyed in boring, easily skippable premission monologues by your commanding officers and informants. Unsurprisingly, the best parts of the story happen during the missions themselves, where you'll often hear Fisher exchanging banter with his off-site crew. Fisher, once again brought to life by gravelly voiced actor Michael Ironside (Total Recall, Starship Troopers), is a great character, thanks to his dry, melancholy sense of humor. But the game sometimes tries too hard to be clever, with a few highly conspicuous attempts at self-referential jokes. At any rate, you shouldn't play this game for the plot.

Fisher is deadlier than ever this time around, thanks partly to his new combat knife, which he has inexplicably started using since his last assignment. The knife is mostly just a cosmetic change from the previous Splinter Cells, since in those games Fisher could put his opponents into a choke hold, whereas he now holds them at knifepoint (bold new look, same difference). Even though he threatens his captives with a knife to their throats, Fisher can't actually cut them once he has grabbed them from behind. He can either choke them to unconsciousness or deliver a fatal knee strike to their lower back. Prior to grabbing them, he can now also stab his foes to death quickly, quietly, and, for some reason, bloodlessly. And though he's replaced his old elbow smash with a palm strike or a punch to the temple, he can optionally still knock his foes unconscious as opposed to killing them outright.

One of the reasons Chaos Theory is easier than its predecessors is because Fisher's melee attacks are more effective, allowing him to reliably eliminate foes with a single, swift attack without even resorting to using his guns. There's actually no difference in gameplay terms between killing a foe and knocking him out. But it is nice to have the choice for variety's sake, although the options could have been more meaningful here. At any rate, it's good to see a bunch of great, new animations in the game. Fisher has always moved with incredibly lifelike grace, but he looks even better in action now. Probably the best of the new animations is how Fisher will naturally shift his weight away from an unsuspecting foe as he creeps up on him, putting as much distance between the two of them as he possibly can. It's a subtle effect that really makes you feel like you're stalking your foes in the darkness. These animations are really the only impressive aspect of the game's visuals.

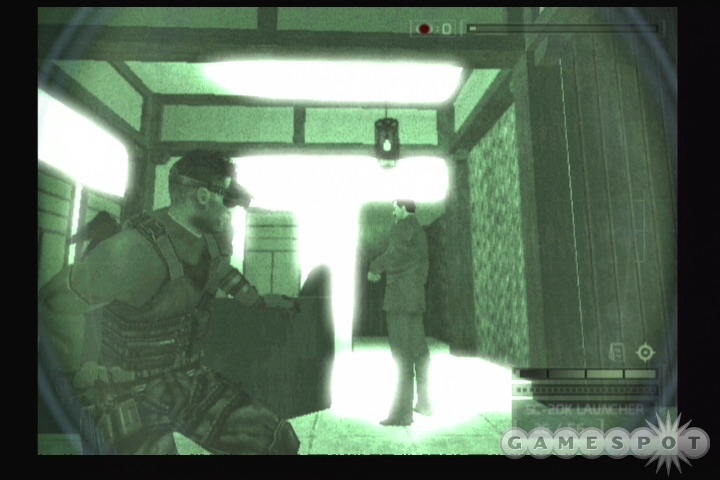

Fisher has a bunch of other surprising new moves here, some of which are possible thanks to the knife, and others that allow him to take out his foes in interesting new ways. However, you won't get to use new moves often; you'll end up using the same sorts of techniques that were central to the first two Splinter Cell games. You'll frequently shoot out lights, switching to your night vision or thermal vision to aid you while your foes stumble blind. You'll also frequently creep up on foes from behind and consider shooting them in the head, using either your pistol or your newly redesigned SC-20K multipurpose assault rifle. In addition, you'll get to pick locks, hack into computers, crawl through air ducts and other tight spots, slip past security cameras, and more.

So, what's so different about Chaos Theory's campaign if you're doing the same sort of stuff as before? It's that the campaign is much more open-ended now. This latest Splinter Cell generally gives you a lot more freedom to pursue your objectives by any means necessary. For example, when faced with a locked door, you don't strictly need to have the key code to get through it anymore--you can now hack the electronic lock or simply break the lock with your knife. The variety is good to have, though it draws attention to the third installment's use of its predecessors' utilitarian system that lets you choose context-sensitive actions like "switch object" and "grab character" from a text menu, rather than letting you perform these actions more intuitively. Also, your pistol now has a secondary firing mode, which can temporarily disable electronics--useful for creating darkness as well as distraction. And whereas many of the older Splinter Cell missions ended in an automatic failure if you sounded an alarm too many times (something that Chaos Theory pokes fun at early on), most of the missions this time don't restrict you like that, nor do they force you to hide enemies' bodies or spare their lives. As mentioned, missions also have optional objectives and sometimes multiple paths to the main objectives. You can even go into each mission with a different arsenal, suited either for stealth, assault, or a balanced combination of the two, though your choice probably won't have a major impact on how you play.

All of this allows you to improvise while playing Chaos Theory, instead of going through a trial-and-error process until you figure out the "right" way to proceed. That's an improvement, though it literally means you can approach most of the game's missions much more carelessly than you could in previous Splinter Cells. In fact, outside of a few specific sequences, Splinter Cell vets will find the campaign to be a walk in the park at the normal difficulty. Still, if you want a more-meticulous challenge, the game offers multiple difficulty settings, the tougher of which are more punishing of tactical errors by making Fisher much more vulnerable to enemy fire.

The international settings of Fisher's escapades are a major highlight on the Xbox and PC, but on the GameCube (and PS2), the settings lack detail and look bland and often dismally dark, diminishing what should have been one of the most appealing aspects of the game. A fairly useful map is always there to help guide you to your next objective, but the missions are designed in a linear fashion that tends to prevent you from getting lost, and not at the expense of seeming overly simple or straightforward. A Game Boy Advance connectivity feature optionally lets you view your map and your mission objectives on your GBA screen, though this low-resolution map is practically illegible. The enemies you'll face in Chaos Theory are also somewhat smarter, or at least different, than before. They'll notice if the lights go out or if a door is left ajar, and they will wander over to investigate. And, if you try to snipe them and miss, they'll flinch believably or maybe even dive out of the line of fire. They'll attack you from behind cover, and they are dangerous in numbers. Most of them are still completely unable to see you when it's dark, so it's really not that hard to quietly creep up behind or around them. But getting to see your foes' new tricks, and coming up with new and interesting ways of distracting them or luring them to you, is definitely part of the fun.

The campaign is close to 10 hours long, and it ends dramatically but abruptly. The several difficulty options, optional objectives, and relatively free-form gameplay make it more replayable than the previous Splinter Cell campaigns. As mentioned, there's also the co-op mode to consider. This mode is endearing, considering co-op modes are grossly underrepresented in today's games, and considering that Chaos Theory's implementation lets you and your partner perform a whole bunch of cool moves that one spy alone couldn't accomplish. For example, one spy can toss his partner over high walls or across chasms, and they may act like human ladders for one another, too. These different co-op moves look great, but they're executed in very specific locations and situations, so their implementation feels somewhat contrived.

Beyond that, co-op Chaos Theory plays just like the campaign, except with two players running around instead of one. Coordinating attacks with a friend can be a lot of fun. The thing is, Chaos Theory includes just four co-op missions (plus a training mission that does little but showcase the various co-op moves you can do), and the one set in Seoul is by far the best. It ties in with the main campaign's storyline and is tightly structured and altogether exciting. The other co-op missions feel a lot bigger and emptier, and they suffer for it. All in all, cooperative Chaos Theory is a great concept that's fairly well executed, but you can tell that more effort went into the single-player campaign than into the handful of derivative co-op missions.

Splinter Cell's famous good looks have always helped the series a great deal, but don't expect to find that in Chaos Theory for the GameCube. As mentioned, the game is sometimes so dark and dreary that it's hard to look at. The environments will constantly force you to toggle your night vision on and off just to get your bearings, and the game often chugs along at a substandard frame rate. Fisher at least looks decent, though his foes lack much of the detail found in other versions of the game, like when you can see the look of terror in their eyes after putting them in a vice grip (here they just look stoic, like they've been there before). Overall, this game's presentation is decidedly bland. It's also glitchy at times. In a few levels, you'll see that texture maps on some of the characters seem to flicker on and off when they are standing in the light. There also seem to be more issues with 3D objects clipping through each other in this version compared to the others. Fisher's animations still look good and everything, but the GameCube can produce a much better-looking game than this. Given how much of Splinter Cell's appeal comes from its presentation, the lackluster graphics really hurt.

The audio is probably the one aspect of the game that didn't suffer much in translation to the GameCube, though at times you'll still wish that it was implemented better. And, in fact, the GameCube version is missing some of the speech found in other versions of the game, despite the fact that the game is on two discs. An original soundtrack by electronica artist Amon Tobin punctuates the campaign and the game's menus, lending a superspy feel to the proceedings whenever it chimes in. As in previous Splinter Cell games, the soundtrack's cues are actually a little haphazard. For example, you'll be skulking about without any background music for the most part, and then the beats suddenly kick in if you alert anyone to your presence or get in a fight. When the coast is clear, the music fades as quickly as it picks up, dampening some of the suspense you might otherwise experience if you weren't sure if other foes were nearby. The music sounds terrific, at any rate, as does the voice work from the game's main cast. Fearsomely loud gunfire and other well-done ambient effects help sell the whole experience, though the game's international cast of characters still speaks in stereotypically accented English. You'll also hear some of the characters' voices noticeably change as they go from chattering with each other to taunting you in a fight. It's not that bad, it's just something that can undermine your suspension of disbelief in a game that works hard to be convincing.

It's almost painful to directly compare the GameCube version of Chaos Theory to its Xbox and PC counterparts any further. It's evidently based on the same stripped-down version as the PS2 game, though it looks a little sharper and lacks the online mode. This version doesn't even control that well, since there are a limited number of functions on the GameCube controller. Actions that are easily accomplished with a button press, such as aiming through the scope of the rifle, must be accomplished using counterintuitive combinations with the Z button here. However, at least it is fairly easy to get used to. Like the other versions, this one includes a few too many unskippable splash screens, in-game advertisements, and undesirable loading times for comfort. Some of the loading times, such as when you save your progress, just seem to take forever. As with the PS2 game, this version also splits both the single-player and the co-op levels into discrete chunks, injecting even more loading times into the proceedings and making the whole game feel more disconnected in the process. It's strange how this version of the game, despite having similar content to its counterparts on other platforms, could fare so much worse in practice. However, all these little things clearly add up to make it this way.

The design of Splinter Cell Chaos Theory's campaign fulfills a lot of the previously untapped potential of its predecessors' single-player portions, and the game's multiplayer options are certainly intriguing. On paper, it has to be the most fully featured stealth action game to date, so if you like the idea of high-tech espionage, it's going to be appealing. The game's different ingredients do seem as if they were cobbled together, though, and Chaos Theory ultimately could have benefited from a greater sense of cohesion. And the many, many sacrifices made to the GameCube version mean that it just can't be recommended in good conscience, despite being a decent game if considered in a vacuum.