Master of Orion is a game with grand scope and massive scale, and more often than not, both work to its advantage. You explore outer space, colonize planets, and swing other leaders on a clandestine dance floor of galactic diplomacy, all with an overarching plan in mind. The problem is, Master of Orion doesn't always make that process fun. It vacillates between moments of exhilaration and periods of boredom.

Commonly referred to as a 4X title (explore, expand, exploit, and exterminate), Master of Orion is a reboot of an earlier series of the same name. The first Master of Orion draws easy comparisons to Civilization, another franchise in which you guide a nation from its nascent years to its swan song through various victory conditions. But over time both franchises have drifted apart, introducing their own twists on the empire-building formula throughout the years.

One of the few notable changes in this new Master of Orion is an optional real-time combat system that allows for a more hands-on approach to inter-fleet skirmishes. You can divert individual ships and focus fire on specific enemies, using the agility of your frigates and the firepower of your battleships to pick apart enemy clusters.

This combat system works well on several levels. Primarily, it adds unpredictability to combat that's otherwise based on mathematics and predetermined outcomes. If your small collection of frigates faces off against a hardened group of cruisers, odds are, the "auto-resolve" option will lead to defeat. But if you take the time to direct your fleet on a micro level with daring maneuvers, you have the potential to upend the odds in your favor.

Secondly, this form of combat narrows Master of Orion's focus from what's otherwise a sweeping look at the history of several civilizations. It drops you from the admiral's chair to the cockpit of a fighter vessel. Not only does it change up each playthrough's pacing, but sets the stage for a fine balance between micro and macro managing your people's development.

This bouncing between big picture problems and minute concerns is where Master of Orion shines brightest. You plot the course of an entire civilization, establish your presence in numerous solar systems, and bring about the end of entire alien races--but you also upgrade your frigates' laser cannons. You bribe the Alkari leader with a few billion credits. You build mining outposts on forgotten moons in the outer reaches of the galaxy. There's a vast difference between the bird's eye view of a political leader and the tactical considerations of a hangar bay engineer. But Master of Orion uses that contrast to its advantage. It links strategy and tactics with seamless ease.

This dynamism between the large and small scale can also change up Master of Orion's pacing, which often becomes rote in the mid-game turns of playthroughs. This problem has plagued the best of 4X strategy games, and unfortunately, this reboot doesn't find any way around it.

Unless you're at the outset of your budding civilization, engaged in combat, or guiding your people in the last few years before that exhilarating grab at military, technological, economic, or diplomatic victory, turns become mundane. Colonies often lack individualism, utilizing the same structures and constructing the same military units as the planets in their neighboring systems. Aside from the occasional thrilling space battle, playthroughs are seldom all that different from the ones preceding them.

Master of Orion's chief allure--the promise of exploring uncharted solar systems--is only novel for a few hours.

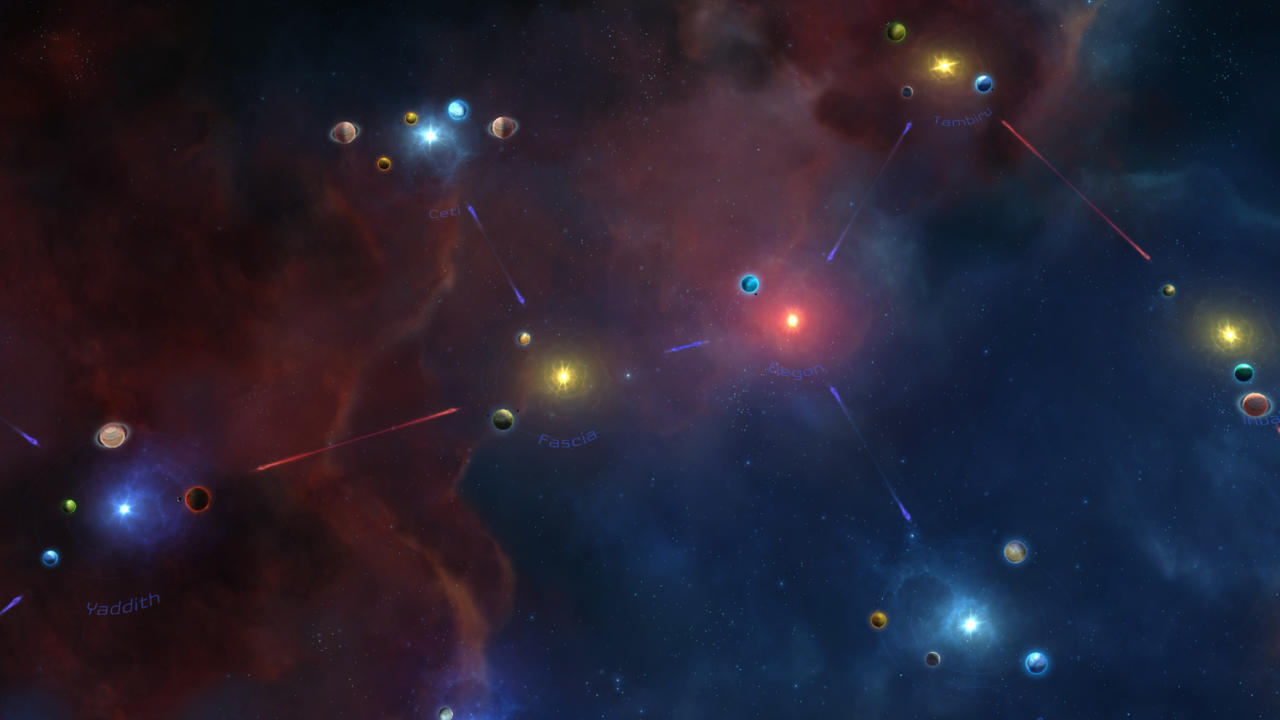

Furthermore, the game's chief allure--the promise of exploring uncharted solar systems--is only novel for a few hours. It soon becomes clear that, aside from a handful of different biomes, planet sizes, and mineral types, there's not enough variety between planets to encourage exploration for its own sake. Maps also lack many surprising discoveries in the space between systems--you'll come across ancient artifacts, stray clouds of debris, and rogue pirate bases, but again, after a few hours, you'll likely see it all. Exploring can reveal bright spots on the sci-fi game's sprawling star map, but also a lot of empty space.

What Master of Orion lacks in variety, though, it makes up for in fine-tuned design. The galactic map, composed of multitudinous star systems and the quantum warp paths connecting them, leads to interesting strategic quandaries for your scouts and battle fleets. Defending individual star systems means guarding warp points and building defensive emplacements around your key settlements. Managing the interlocking web of colonies and the established lines of travel between them is key to preserving your people, or destroying someone else's. This is supported by the combat system, which pierces through the ennui of Master of Orion's exploration.

There's another web at play here: the diplomacy system is a minefield of bad tempers, interlocking alliances, and cultural pet peeves. The leader of the Sakka Brood, a reptilian race, doesn't value scientific advancement, and because of this, won't trade credits for your advanced technological knowledge. The Skylord of the Alkari Flock is aggressive by nature, and will declare war if you demonstrate too much good will toward the civilization's enemies. Master of Orion's diplomacy system isn't a separate entity from the rest of the game, but the foundation of many other mechanics. It excels in making you consider your diplomatic choices. It lends weight to hefty decisions elsewhere in your unfolding nation.

The presentation of these various alien races, and the emotions motivating them, drives home a personal touch in a game that otherwise focuses on sociological management and technological progress. The voice acting grounds the alien leaders and makes them feel like real characters. After several full playthroughs, I know to never trust the silver tongued Darlok. I know to be on the defensive around the Terran. I know the Bulrathi are valuable allies in a tight spot. Master of Orion succeeds in depicting intergalactic events in a smaller, more intimate context, and it lends compelling reasons to steer your civilization one way or another.

And that's the thing about Master of Orion: there are plenty of weighty decisions, risky maneuvers, and impactful events to consider. But they often take place in repetitive playthroughs in galaxies that don't always differentiate themselves from the next. Master of Orion shows signs of brilliance, but it's bogged down by boredom, and sometimes, the allure of the stars wanes too much to beckon us onward.