The arcade may be dead in the United States, but many arcade-style games are finding new life on the PC. Intake steps in as an excellent light gun game, reminiscent of a strange mash-up of Ikaruga and House of the Dead, built on a tongue-in-cheek presentation of rave and drug culture. It's a curious marriage, but one that works well, creating an exceptionally satisfying, brutally difficult modern reinterpretation and refinement of classic mechanics.

Running Intake for the first time opens a menu with three graphics options--Pep Rally, Dance Party, and Sparkle Party--and these options make for an accurate introduction to the frenetic shooter. Intake is a game about drugs...sort of. There's no serious political message besides the 1980s arcade callback screen showing the phrase "Winners Don't Use Drugs." Beyond that, there isn't even a direct reference to anything illegal, but the intent is clear.

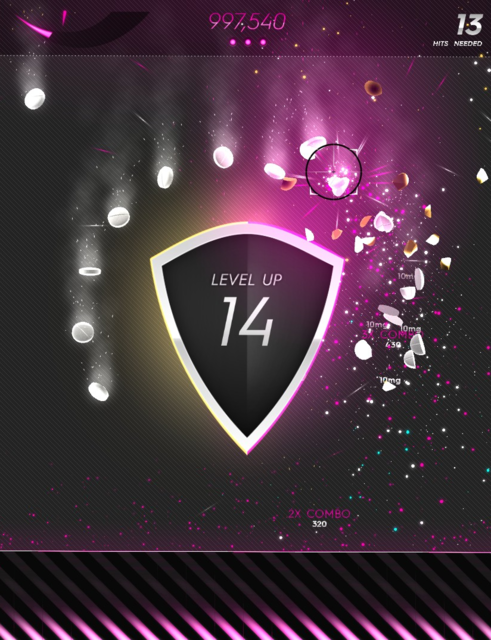

During play, you're assaulted by a never-ending stream of colored pills falling from the sky. The right mouse button changes the color of your cursor, and the left mouse button destroys whatever pill is in your reticle. At the bottom of the screen, you have a "shield" that blocks any pill that doesn't match the color of your cursor. Each level has only two colors, to keep things simple, but every level changes up the palette to a new set of vibrant, neon-soaked hues. If a pill falls below your shield and you don't manage to destroy it before it falls off the screen, you die of an overdose.

Those are the basics, but the bare-bones tutorial doesn't even say that much. Advanced mechanics, such as chaining combos, snagging power-ups, and something I've come to call "bumping" pills, are never mentioned or introduced, which is a shame, because these advanced bits make Intake compelling.

Each pill you hit with the properly colored cursor starts or continues a combo. If you miss your target, however, the combo drops, and you need to start over again. If you destroy a pill with your shield, you're safe, but you don't get any benefits. Combos are critical because they act as score multipliers that increase the in-game currency yield of each round. The points you earn, appropriately measured in milligrams, are used to unlock more colors, more music, additional lives, and power-ups. As the pace of the game picks up, all but the best players will be lost without these power-ups and extra lives, so unlocking them as early as possible is important. There's a decent variety of power-ups as well: one increases the size of pills to make them easier to hit, another one slows down time so you can pick them off with a bit more accuracy, and yet another launches a bolt of lighting that bounces between pills destroying each one it encounters up to a preset limit. Which power-up you get is randomly determined, but you can unequip the ones you've unlocked to limit drops to the one or two you like the most.

Intake draws heavy inspiration from modern rave culture, a sort of bass-driven sensory overload environment where you and the other club-goers teeter on the brink of mental breakdown tapping into the state of mind that stands as the namesake for one of the scene's most popular substances. Aesthetically, Intake captures the feeling almost perfectly. It's loud, obnoxious, and altogether trance-inducing. When the game really got going during intense challenge matches or in some of its later levels, I felt myself achieving a sense of flow that's remarkably uncommon in a fair portion of today's games. Play becomes euphoric as the pace increases--faster and faster--and once you've built up a decent momentum, the experience is unreal.

Intake is a spectacularly minimal game that contains a staggering amount of complexity with just a handful of straightforward concepts.

Achieving that state is easy because everything fits together so comfortably. Everything you can do presents its own risk/reward payoff, and Intake asks you to make so many choices so quickly that, at best, you end up operating on instinct and playing with sheer technical skill. If, for example, you finish a level while an untriggered power-up is on the field, it explodes into a small starbust of tablets, each worth 10 milligrams. Those can, in turn, collide with the tablets that appear in a rainbow shape at the end of every level, making it harder to hit them all and pick up a small completion bonus. Wildly clicking to hit all of the end-of-level tablets helps for a few seconds, but as soon as the next level's pills start falling, missed clicks suddenly count against you once again, and you risk dropping your combo. Picking up extra in-game currency becomes a challenge to gather as much as you can before you risk killing the very thing that multiplies the currency you can pick up.

Perhaps an even tougher choice on the higher levels is whether or not to grab an extra life. On the one hand, it can replenish the one resource that keeps you clicking away at pills longer. On the other hand, the extra life releases a burst upon collection that typically pushes all the pills onscreen closer to the edge, and much like those pills, once the collectible is off the map, it's gone and you're out of luck.

Challenge levels push your skills and the criticality of snap decisions to the limit starting after level 25. There are four different types. Flood stages do just as their name implies and slowly fill the screen with countless pills, typically far more than you could ever hope to click through. Acceleration does just the opposite, sending a few pills rocketing across the screen at insane speeds. Minefield uses an abundance of flashbangs, which are colorless pills that freeze your screen for a second, causing you to lose track of standard pills. The last is called Reaction, and it makes nearly all of the pills detonate violently upon destruction. Typically, that's a good thing, since it wipes out a good chunk of pills all at once, but in this case, careful clicks are the only thing that stand between you and dozens of stray, hypervelocity bits of "medicine." These stages are randomly triggered and mixed in with the normal ones, keeping the level of challenge on the ridiculous end of the spectrum throughout.

Intake is a spectacularly minimal game that contains a staggering amount of complexity with just a handful of straightforward concepts. The only issue, besides the aforementioned semi-useless tutorial, is the exceptionally small music selection. While the tracks are excellent, it's odd that there are only three. The backbone of rave culture is exciting, pulsing music, and more is always better. I've dumped a good 10 hours into the game so far, and I can't say I'm sick of any of these songs, but that might not be the case for everyone.

Games that can, through abstraction, accurately capture the distilled essence of a much larger experience are truly special. Intake is one of them; it uses a few simple ideas to build a complicated affair. It's not quite the relaxing, surreal Dyad, but it does tackle the kind of frenetic, euphoric atmosphere of the modern electronic dance music scene. If you have even the slightest appreciation for score challenges, shoot-'em-ups, or light-gun anything, Intake will keep you popping pills for quite some time.