Choice. Many games provide the illusion of it; fewer deliver it in any meaningful way. Deus Ex: Human Revolution is one of those few: a first-person shooter/stealth/espionage/role-playing hybrid that allows you to overcome obstacles as you see fit. Let's say you require access to a guarded apartment building. You can shoot your way past the patrolling sentries. But maybe you'd rather sneak past them unnoticed, silently knocking them out as you go; hack an electronic lock on a side entrance; or find a hidden vent and shimmy your way inside. Play the way you want: It's up to you. In Human Revolution, this kind of flexibility can be awe inspiring, but like with many ambitious games, the individual parts and pieces aren't always satisfying on their own terms. Neither the shooting nor the stealth is best in class, and a number of flaws disrupt your suspension of disbelief. But even if the details don't stand up to scrutiny, taken as a whole, Human Revolution is an excellent game with an unsettling vision of the future we face.

In that future, human augmentation has changed the way we live. Augmentation technology makes the more fortunate among us stronger, faster, and hardier--for a cost, of course. It's the year 2027, and the world is divided. Some believe that augmentation is the next step in evolution; others think it strips us of our humanity. Sarif Industries is one of several companies that research and manufacture such technology, and you play as Adam Jensen, Sarif's security expert. Scientists are on the verge of a mysterious breakthrough when high-tech soldiers ransack Sarif's headquarters, making off with important info, apparently murdering scientists and leaving Adam for dead. Sarif rehabilitates Adam with the help of augmentations, turning Adam into both man and machine: something beyond human. As Adam, you set off to discover who was behind the attack and what, exactly, they were trying to find.

As it turns out, you uncover more than you expected. You explore Shanghai and your home city of Detroit, along with other locales, to piece together clues. Some of them illuminate plot elements; others flesh out the world as a whole; while still others provide unexpected personal data and set the stage for a surprising turn of events. In this grim vision of the future, anti-aug demonstrators hang on their prophet's every word; sexual deviants seek augmented prostitutes for extra thrills. Human Revolution explores the symbiotic relationships binding the press, the government, and big business--a modern, relevant theme that gives the story an air of disturbing authenticity. If you played the original Deus Ex, you will appreciate seeing the origins of the turmoil to come, before nanotechnology further revolutionized the human condition. Electronic books you stumble upon hint at the coming innovation; newspapers document increasing social tensions (and, cleverly, refer to how you completed your most recent mission); and emails and PDAs provide insight into the minds of the game's key figures.

The visual design does a great job of setting the stage for those tensions. Human Revolution's color palette makes frequent use of gold and black, which results in eye-catching visual contrasts. Take, for example, a nightclub in Shanghai called The Hive. The honeycomb design stretching across its neon yellow exterior is not only striking, but also similar to interface elements associated with augmentations. This kind of thematic and visual consistency is common and makes for a cohesive atmosphere even when trotting across the globe. Human Revolution takes great pains to be believable and immerse you in its world, which makes its technical deficiencies all the more noticeable. The city districts you explore are good sized but not enormous, which makes the extended loading times between them seem drastic. You spend minutes at a time in lengthy conversations, staring at the dated, mechanical facial animations. On the Xbox 360 in particular, the frame rate can take a hit as you pan the camera around--a distraction in any case and a greater annoyance during firefights. On consoles, it feels like developer Eidos Montreal tried to squeeze a bit more out of its graphics engine than it could handle. On the PC, the game performs adequately but still looks slightly dated. But this is a case in which good art design overcomes the technology that renders it. The game is as much about places as it is about people, and it does an excellent job of giving its environments character and grit.

And so you perform story missions and side quests in these cities, where hobos huddle around flaming barrels for warmth and private security firms intimidate the locals. You find answers for a grieving mother, publicly humiliate a cowardly murderer, and seek a dangerous hacker. And in most cases, how you accomplish your tasks depends on how you wish to play. Let's say you must make your way through a heavily guarded facility. If you prefer the direct approach, you could shoot your way through. During the course of the game, you find or purchase pistols, revolvers, combat rifles, shotguns, and more--and you gain access to augmentations that further support your violent tendencies. As you play, you earn experience; in turn, you then earn praxis points used to unlock new skills and enhancements. Players into bloodshed should appreciate the dermal augmentations that increase your armor, reduce weapon recoil, increase inventory space, and improve resistance to concussion grenades. From the action-packed perspective, Human Revolution plays like a cover shooter. When you snap behind cover, the camera pulls into a third-person view, and you peek out or pop up to load your enemies with lead.

The shooting mechanics are fine but not outstanding. The cover system works well, but even with dermal upgrades, you are still fragile enough to feel in danger when you engage the enemy. And ammo is scarce enough (though not frustratingly so) that you'll want to make every shot count. Unfortunately, the none-too-smart AI frequently diminishes that sense of danger. It isn't uncommon for enemies to empty clip after clip shooting at the wall you are hiding behind, refuse to shoot back even when you're pumping bullets into them, or jump en masse into a grenade rather than away from it. Actually, it isn't just enemies that act in unconvincing ways. In many cases, you can tap away at people's computers right in front of them, saunter into a shopkeeper's storeroom to steal credit chips and ammo, and emerge from air ducts right in front of fellow Sarif employees. For what it's worth, the previous Deus Ex games also featured such illusion-breaking details. And like before, those details stand out because the game otherwise works so hard to create a believable cyberpunk world.

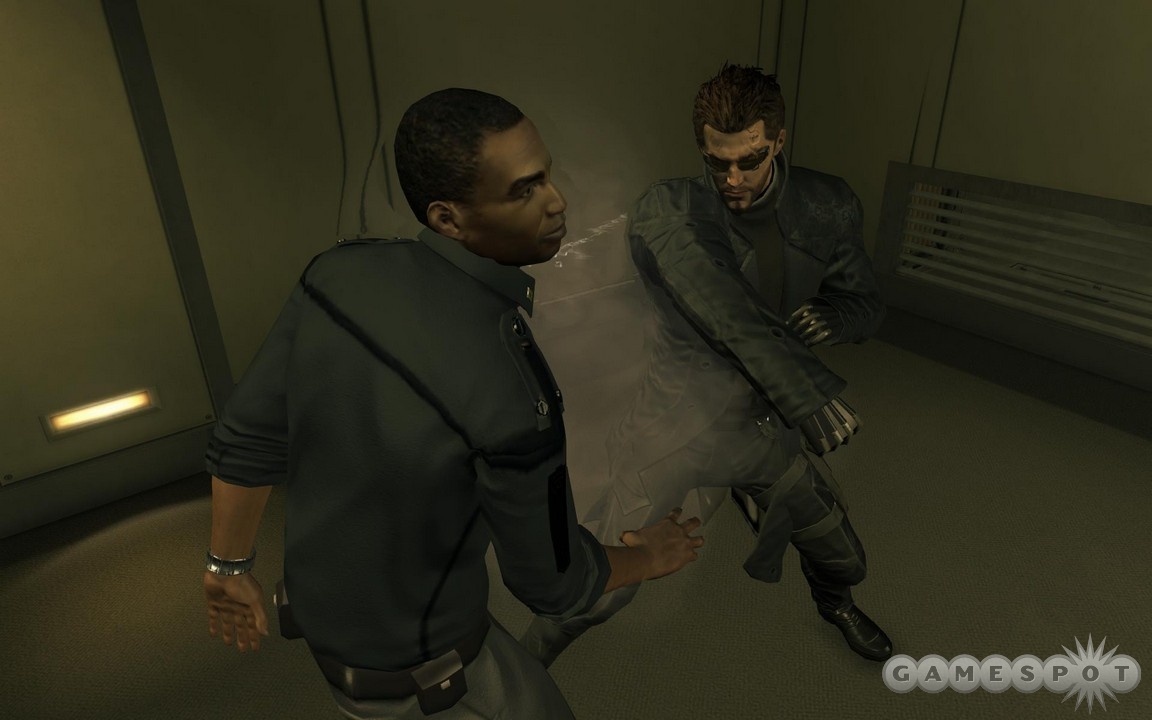

You don't have to shoot anyone on your way through that aforementioned facility, however. There are good reasons to take the nonlethal route. One is that you earn extra experience for leaving your foes alive; another is that it's more satisfying to sneak than to shoot. That isn't because the AI magically improves when you go stealthy; while you are crouched, a guard might walk up to you, his crotch in your face, yet not notice you. But patrol patterns make it challenging--though hardly impossible--to elude notice. If you played Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell: Conviction, the stealth gameplay will feel familiar. You can tumble from cover spot to cover spot or press against walls and obstacles to remain out of view. And again, the right augmentations can complement this play style. In this case, they take Human Revolution from plain-Jane sneaker into fully featured stealth game. Eventually, you can observe enemy figures through walls, see their cones of sight on your minimap, or mark them with pips to make them easier to track. But even while sneaking, you can feed your hunger for violence with a melee attack. If you're feeling generous, you can clobber your enemy but leave him alive and earn a few extra experience points for your kindness. Or, you can forfeit the extra experience but get the rush of a vicious assassination.

These takedowns are accompanied by canned animations. The camera pulls out as you watch Adam knock some sense into a guard (or two guards, with the right augmentation) before returning to the game. These moments are often dramatic, but like other parts of Human Revolution, they can also disrupt the atmosphere the game works so hard to create. Your target might teleport to a new location for cinematic purposes or clip through a wall or another enemy. Meanwhile, any other characters in your field of view are frozen in place as if time has come to a momentary standstill. Such foibles aside, takedowns are a satisfying way to release the tension that naturally builds as you carefully inch ahead. And there are other gratifying payoffs to successful stealth. Some areas are guarded by robotic sentries--some of them large and intimidating. You could throw an EMP grenade in their direction, which results in a brilliant eruption of metal and sparks. But it's even more fun to hack into a security panel and turn them against their unsuspecting masters, though again, you need the right augmentation to pull off that technique.

Then again, you could discover other alternate points of entry. If you're strong enough, you can gain access to conveniently human-sized air ducts by moving vending machines and trash dumpsters out of the way. If you can jump high enough, you might leap a fence that stands behind you and the area you must access. Another augmentation allows you to see weak points in walls and punch through them. (Like stealth takedowns, this move results in a canned animation.) You might pluck a PDA with security codes from a corpse that allow you to open doors or access emails--emails that might contain even more such codes. You might also find PDAs sitting around on occasion. In Deus Ex: Invisible War, such codes were so easily found that the whole idea came across as relatively contrived. In Human Revolution, you might find such codes in hidden areas within a sewer or on a computer in a remote office. Because they aren't always found in ultraconvenient locations, the whole business of espionage feels less artificial. The game encourages you to thoroughly scavenge; whether you find codes, ammo, or a weapon you hadn't seen before (hey look: a laser rifle!), there is always an advantage to opening a row of lockers or getting into a locked storage area.

Don't worry if you can't find a relevant code, though. Hacking is a particularly enjoyable way of getting through locked doors. In the previous games, hacking was a mostly hands-free affair. Now, you must perform a minigame that involves creating a digital network path before the computer can shut you out. At higher levels, some locks can be rather tricky, though you can find hacking programs that ease the challenge. Some areas--a newsroom, for example--are full of computers begging to be hacked, and there are enough story tidbits, humorous Easter eggs, and other secrets to make it worth checking them all out. Hacking can get rather addictive, so don't be surprised if you lose 30 minutes or more just opening every lock you can find. But the joy doesn't just lie in the hacking on its own, but also in the context of such freedom. You could play as primarily a hacker, a sniper, or a sneak, but Human Revolution is flexible enough to let you mix and match as you see fit. If you get caught creeping around a rooftop or hacking a lock, shooting your way out is a viable alternative. If you tire of one approach, there's always another to try. And even when you arrive at your destination, you might see a vent in the corner and realize there was another way in that you never discovered.

You can even talk your way out of (or into) certain situations if you so choose. Some characters respond well to empathy; others prefer tough love. If you prefer charming your way past obstacles, you will enjoy the related augmentation, which unveils personality details on your conversation partner, among other helpful features. Adam himself doesn't infuse these talks with much character. He speaks with a dispassionate rasp, whether you respond to others with anti-tech rhetoric or empathize with your fellow augs. That said, he's much like the original's J. C. Denton in this regard, which should delight fans who want Human Revolution to be closer to that game than the oft-maligned Invisible War. In any case, your dialogue choices influence how certain quest details play out and might open up additional avenues. (For example, you might be able to gain unhindered access to a police station rather than have to sneak around.) Furthermore, your decisions determine which of the game's several endings you receive.

It's both fascinating and frustrating that Human Revolution, a game that's special precisely because it allows you so much freedom, would occasionally force you into a single style of play. This is especially true of the boss fights, most of which turn this free-form, do-it-your-way role-playing action game into a shooter. This may not annoy you too much if you've been playing it as one, but if you've built yourself up as a stealth star, a hacking hero, or a jack-of-all trades, boss encounters are not a welcome change of pace. Not only does forcing you to shoot feel out of place in a game that generally rewards you for keeping your foes alive, but the fights also aren't that fun on their own terms. Once you figure out your enemy's pattern, you just repeat the same moves until you whittle down his or her inflated life bar. (A life bar, mind you, that you cannot see.) On the flipside, a few side quests require you to hack locks of a particular level, which might frustrate action-oriented players who don't want to forgo the quests but also don't want to be forced into buying augmentations they don't particularly want.

Don't let these imperfections dissuade you from playing Deus Ex: Human Revolution if you're so inclined. This is an extensive (20-plus hours) game that by the very nature of its complexity invites replay. It is true that many of its individual elements don't withstand close inspection. But those elements add up to an impressive and absorbing adventure that invites you to improvise. You glide from rooftops like a cyberpunk angel in a world on the brink of technological breakthroughs and socioeconomic disaster, and uncover conspiracies in the unlikeliest of places. The longer you play, the more the story grabs you and the more you appreciate the customizability of the game. Hybrid games like this are uncommon. Even more uncommon are games with Human Revolution's power to eclipse its quirks with such enthralling atmosphere and exciting adaptability.