Revisiting Horror

For a long time now, haunted house amusement rides have had a special part in popular culture; the seduction of entering such an ominous location feeds on a primordial instinct to face dangerous situations in controllable environments. "Resident Evil" is surely meant to be played as if a haunted house ride, and what better evidence of this fact than the change from its original Japanese title – "BioHazard" – to the sillier, yet somehow more accurate western translation? Like in "D", "Resident Evil's" mansion is designed with a stunning sense of ambiance that hints at danger in every corner. More than the actual fright – of which the now infamous dog leaping sequence has become a symbol – it's in the anticipation and build up of tension, through visual and auditive cues, that the authors' deviousness became fully apparent… Hitchcock would surely be proud. It helps that the mansion bears such a portentous and ostensible visual characterization, in both scale and intrinsic detail of its decor, making it humbling to the player. The mansion is, in itself, a work of art – its rendition of paintings, sculptures and architectonic style, thoroughly embodies the concept of an interactive art museum, so in vogue in the mid-nineties. The photorealistic quality of its pre-rendered visuals made the game not only aesthetically beautiful, but also more effective in heightening the sense of presence on part of the player.

These were the notions which the sequels could never truly evoke. "Resident Evil 2″ and "3″ no longer took place in claustrophobic, XIXth century mansions, but instead spread the action across an entire city – the dimensionality of the urban landscape inevitably gave a sense of liberty and breathing space to both titles. The often criticized clunky movement of characters – so important in forcing players to acknowledge the dangerous, uncomfortable and uncontrollable nature of their surroundings – was, with each title, softened thanks to new movements and more responsive controls. The scarcity of weapons of the original was slowly amped into a considerable array of weapons, more powerful and plentiful with each passing iteration. In "4″, besides a diminished role of exploration and puzzle sections, the cinematic angles were replaced with a pure 3D camera – meaning that zombies could no longer jump from out of the screen unseen. "5″ borrowed its aesthetic and ambiance from other games, further compromising and indeed erasing any memory of the original work that was still present in the series. All of these games bore 'good' design decisions, sure: each made "Resident Evil" a 'better' game, i.e. less frustrating and more fun. But with these nefarious changes it also lost its identity, its charm, and most important of all, its capacity to frighten players, reducing a once great adventure horror game to a mindless action shooter.

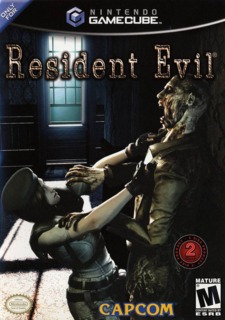

Which is why the Gamecube remake of the original "Resident Evil" makes even more sense today than it did back in 2002 – it serves to reminds us of how much the original surpassed its direct (and indirect) successors. Mikami's return to his original masterpiece only served to state the obvious: the series' numerous additions and revisions were unneeded, and more importantly, only hindered at conveying the sense of suspense which uniquely identified his original vision. Instead of re-envisioning the game completely (as he would later do in "4″), Mikami focused on getting players to experience what they had experienced many years before – the sense of entering a beautiful, yet menacing haunted house. Narrative-wise the game is identical, and in terms of game play style and level design it is similar enough to capture the original's spirit, but different enough to stand on its own. Shooting zombies finally became, once again, a conflict with the game itself, a peak in tension that served as a mere punctuating mark in a vast score of exploratory moods. Make no mistake, the remake is not an action game.

Mikami cleverly manages to use the remake to reference other games, like "Clocktower", and even parody "Resident Evil" itself, but unlike Kojima, he does it with such delightful subtlety and consistency with the fictional backdrop that nothing ever feels out-of-place. He can make the most obsessive and knowledgeable hard-core fan smile without needing to break the fourth wall or giving away the irony of his playful demeanor with an obvious joke. Of course, what most gamers will appreciate in the new version of his classic, isn't the elegant revisionism, but the update in presentation. Technical digressions aside, "Resident Evil" makes for one of the most beautiful and immersive experiences in recent video games. Every new animation and lighting scheme adds up to a stunning work of mise-en-scéne for each room, which truly makes them shine as part of a virtual art exhibit. The soundscape completes the picture, making the game's atmosphere as evocative and scary as possible. This remake is one of those rare occasions in which the audiovisual lift was actually used, not as a means of justifying a buy for the tech-savvy buyers, but as a way of furthering the vision of the original work.

Alas, the remake is a memory of a now distant past, a throwback to a time in which games could still balance an underlying commercial logic with an artistic drive that went beyond the confines of fun-inducing game design. "Resident Evil" is slow-paced, clunky, unpleasant and sometimes even frustrating, but only because those are the needed qualities for a survival horror title to elicit a proper emotional mindstate in players. Back in 1996, "Resident Evil" defined the genre, and perhaps not surprisingly, most of its qualities remain unsurpassed still today. Which is why the remake, with its stunning artistic complexion, that so thoughtfully brings the original's ambiance to new heights, is as worthy of the masterpiece title as the original.