D.I.C.E. 07: Spore is not all Wright

Will Wright brings his team of designers to talk about the challenges of making a complex game simple, letting users feel smart, and Care Bears fighting Klingons.

LAS VEGAS--Conceptualizing a complicated game is simple. Just ask Maxis' Will Wright. The mind behind the upcoming PC game Spore has oodles of ideas on how to make a game deep, layered, and complex. However, translating those ideas into actual gameplay is a whole other task.

But if that were all there is to making a game as rich as Spore, there would be thousands of Will Wrights and thousands of Spores, Sims, and Sim Citys.

The real trick, Wright explained, is making a complex game easy to play. This was the subject of Will Wright's presentation at the D.I.C.E. Summit this afternoon in Las Vegas, which was given to a packed house in the Green Valley Ranch's Grand Ballroom.

Wright was accompanied by four main components of the Spore team and about two million slides, which served to both inform and entertain. The four team members--Ocean Quigley, Chaim Gingold, Jenna Chalmers, and Alex Hutchinson--gave the vast majority of the presentation, each describing their experience with their roles in development.

It was an unusual sight to see Wright not alone in the spotlight, but it was also very telling. While Wright is the lead designer of the game, the multiple facets of the game that make up Spore are overseen by Quigley, Gingold, Chalmers, and Hutchinson. And with the frequent reference to "toys" and friendly ribbing, it was almost like watching Santa Claus moderate his elves.

Wright sat at a computer on the right side of the stage, controlling the breakneck speed of the slides whirring by on a large screen on the back of the stage, while his four coworkers sat in folding chairs in the center of the stage, each taking turns talking.

A brief introduction by Wright revealed that creating Spore was not a simple straight line. Developing what Wright had in mind for the game called on a flood of ideas and approaches. In fact, only about 10 percent of the ideas that were seriously considered for the game will actually end up in the final version.

Quigley led off by talking about creating the game's creatures, textures, buildings, vehicles, planets, and objects. Because the game's content is created by users, assembling the building blocks of what will later become creatures is more than a simple process of taking concept art and blowing it out into a 3D model.

"In this game we have to make the parts so that the players can make stuff, and we have to make the systems to give them an illusion of competence," Quigley said without a hint of sarcasm. He also had the difficult problem of making believable, yet fantastic, creatures look and move correctly.

The same problems applied to the buildings, vehicles, and planets--each made with a library of deforming parts. But in the end, it was the desire to make a game that wasn't limited that drove the group.

After a slide came up showing an X-Wing from Star Wars, Wright said that they can't ship the game with Star Trek's Enterprise in it, but they want the user to be able to build it.

"It's pretty satisfying to fly around in your X-Wing and blow up The Enterprise," said Quigley.

"You can have an interstellar war between the Care Bears and the Klingons," said Wright, to a chorus of laughter.

Gingold, a former intern of Wright's, spoke next about his involvement with the object editors in Spore. Much of the design of the editors was done by reverse-engineering toys. He asked himself what made these toys fun and how that could be incorporated into user-friendly editors.

Several prototype editors were created for the game, and at their core they took care of one task--attaching limbs to bodies, texturing skins, and so forth. But they all had one thing in common; they all had to be incredibly user-friendly, yet retain the complexity the designers intended.

When testing the editors, Gingold lived by the mantra "If you don't notice that it sucks, then it must be good."

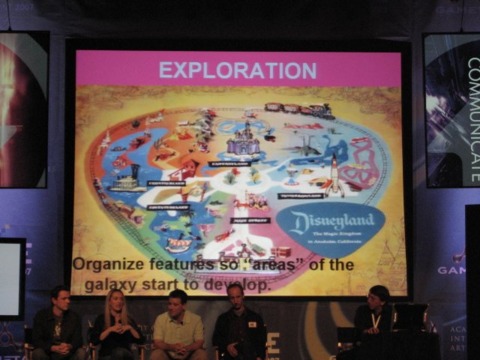

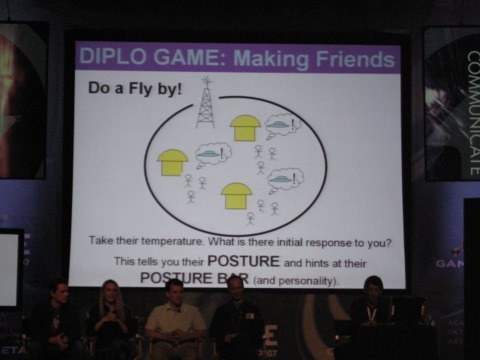

Chalmers was up next, talking about the outer-space portion of the game, which Wright says is "where the game really opens up." He wasn't joking.

Several slides showed almost an endless number of ideas for the space portion of the game, including colonization, combat, worship, missions, and more, all of which were referred to as "metagames." Each game appears as though it could be an individual game itself, and Chalmers' ideas could be summed up in one word: ambitious.

Her portion was an inside peek into how a game was structured, from beginning to end. She started with asking her team what they would want to do if they could go into space (among the answers: blow s*** up, abduct, leave your mark) and then went about fleshing out each option to near ridiculous proportions, all wonderfully illustrated with flowcharts on slides.

However, the lesson learned was that too much open-endedness can be a bad thing and that sometimes some favorite ideas have to get the axe in order to make the overall game that much better.

Last up was Hutchinson, who lead the design of Spore's overall gameplay. "We challenged one of the core rules of game design: Don't mix genres."

But that's exactly where Hutchinson sees Spore at its strongest. When gamers go from the cellular level to the creature level to the tribal level and onward to outer-space exploration, it's aimed to give gamers the feeling of the power of 10 by pulling their perspective further and further out.

"Games usually succeed by saying once you learn something, it sticks. You stick with this piece of information...we're going to add more information to that," said Hutchinson. "Whereas we're saying, 'Yeah 50 percent of what you learned sticks; the other 50 you don't need to worry about [as you progress].'"

After countless slides and enough information to change one's hat size, Wright closed up the presentation with, "There is a trend of games to be less complicated...which is almost at odds with this game. But I think there's a balance you can achieve [between deep games and pick-up-and-play games], but it takes a lot of exploration."

[For a different take on D.I.C.E. 2007, take a look at the GameSpot News Blog, containing interviews with Myst Online's Rand Miller and Lord British himself, NCsoft exec producer Richard Garriott.]

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation