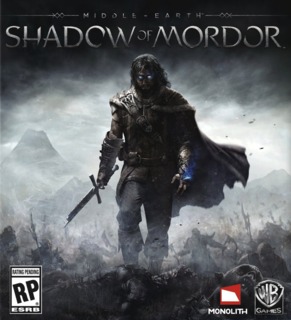

The works of J.R.R Tolkien have continued to enthrall, inspire, enchant, and beguile a number of readers, since the first book of his best-known series, Lord of the Rings, was published back in 1954. Since then, his works have been interpreted as films, and most recently, in the realm of electronic entertainment, as gaming experiences. The world of Middle Earth continues to set a fire in our imaginations, prompting us to wonder what untold tales may take place there, within its many foreboding structures and lost caverns. Shadows of Mordor gives us one such tale, set in one of Middle Earth’s most foreboding lands, and in so doing, creates a unique, but dispersed narrative. Shadows of Mordor makes a perfect case for the belief that to experience literary works to their fullest enjoyment, one should stick to the original works themselves.

Our narrative begins with the protagonist, Talion, described in game only as a “Ranger from the Black Gate”, victim of a family destroying tragic series of events, leaving him as the only survivor. This tragedy forces a shared bond with a spirit who shares his body at times, allowing for the possibility of a wide array of combat abilities and skills. Talion is by no means immortal, however, he is able to accomplish much more than most mortal men.

The skills and abilities that Talion can learn range from simple combo moves, to a deadly ballet with his three primary weapons, a sword, a bow and a dagger. As you progress through the game, earning experience and ability points, by completing missions, and dispatching the game’s seemingly limitless hordes of orcs and uruks, you’ll gain access to new skills, and upgrades, from increases in your health and focus meters to various finishing moves.

Gameplay wise, the open world exploration sections will feel familiar to those who have experienced the motto, “Nothing is true. Everything is permitted.” Talion moves with the fluid grace of a warrior who has danced with death before and has no time to stop for it. Combat is quick and brutal, and finishing moves are often viscerally satisfying.

Graphically, the land of Mordor is painted in the somber tones of grays and burnt siennas. Smaller orc camps and larger strongholds dot the landscape. The captains and warcrchiefs are appropriately menacing and imposing as well when they make their appearance and visually striking.

The land of Numen, where the second half of the game takes place, is a lush valley of green, which seems woefully out of place in Mordor. Waterfalls and reflective pools are a nice touch, but “in the land of Mordor, where the shadows lie,” it comes across as a stark contrast to the grim textures and muted palette that permeates the rest of the game. It’s as if the artist suddenly ran out of colors and decided that bright green would be an adequate substitute.

This is a shame, as there are some wonderful visual touches throughout the world. Rain not only slickens Talion’s leather garb, but manages to seep into his hair and bounce off his shoulders. His blade, Urfael, has a lovely cerulean glow when your hit streak is charged, letting you more easily slice through hordes of enemies, with a subtle nod to the underlying lore. Sadly, these moments are few and far between.

There are also some rather interesting mechanics at work in the game as well. The hierarchy of command, or food chain, if you will, consists of legendary or elite warchiefs, then elite captains, then regular captains, and finally, low ranking normal orcs. When you are slain by a random orc, it gets promoted, acquires a title, a power level and a list of strengths and weaknesses. If you seek to challenge this enemy again, it will seemingly remember having killed you, and perhaps taunt you, before attempting to finish you off again. Dying once more means increased stats for this same enemy and perhaps a promotion in the overall pecking order.

You can actually have fun causing havoc in the hierarchy of power, by issuing death threats to higher ranked warchiefs through their lower ranked subordinates and pitting certain captains and warchiefs against each other. You can also “invade” events held by certain warchiefs or captains, shown on the map, to weaken their power or prestige considerably, or kill them off altogether, if you’re so inclined.

Hunting the legendary warchiefs at the top of the food chain isn’t always as easy as it sounds. After locating them, you’ll want to “interrogate” certain low ranking peons or find documents containing intel or their strengths and weaknesses. Most of the time, you’ll find higher ranking orcs will contain very few weaknesses and a very long list of strengths.

Once you succeed in drawing them out, usually by dispatching a number of their minions, they arrive on the field with all the flair of a top tier WWE Superstar, a deafening chant of their name, plus a posse of suitably high level bodyguards. Killing one of these leaders removes them from the food chain completely, and in time, another lower ranked orc or uruk will take their place. This hierarchy, while at first glance, is seemingly complex and interactive and filled with nuance, becomes markedly less so the more hours you invest in the game. Underlings quickly replace slain enemies, so even their mortality carries little weight in the grand scheme of things.

Speaking of narrative, none of it actually works in the context of the literature. Tolkien’s world is rich with recurring themes that Shadows of Mordor either tramples on or disregards completely. One of the prevailing themes in Tolkien’s world is that of absolute power corrupting absolutely. We see this in many cases in the literature, from Sauron, to Saruman, and even eventually to Frodo. Shadow of Mordor touches on this theme in places, but only in fleeting moments. The game is much more concerned with revenge and killing. Revenge isn’t even an element in the literary works; no one goes on revenge killing sprees in Tolkien’s world.

The glorification of death in Shadows of Mordor directly contradicts the treatment of death in Tolkien’s world, where it is usually seen as a somber, dignified time. Life is cheap in Shadows of Mordor, and as a result, death, for both enemies and the player, is almost inconsequential.

One could even argue, if one were so inclined, that Shadows of Mordor suffers from the inevitable disease of chronic misogyny. Whereas in Tolkien’s literary works, there were a number of strong women, that defied gender norms and customs for the period, women in the game have been cast as little more than stereotypical tropes, like the prophetic queen, the messenger, or the sacrificial lamb. The land of Mordor may offer numerous opportunities for career advancement, coupled with terrible job security and almost no fringe benefits to speak of, but even worse is the fact that equal rights is probably not even on the menu.

If C.S. Lewis’ quote about the first book of the Lord of the Rings holds true, that it arrived like a “bolt of lightning from a clear sky,” then the appearance of Shadows of Mordor is remarkably less so. The fluid combat and somber visual design are heavily counterbalanced by the lackluster and often ham fisted narrative, and misogynistic cast of characters. Perhaps the well used line from the literary world, “One does not simply walk into Mordor,” makes the case more elegantly and more succinctly than any review.