INTRO:

It is not very often that game-makers would make a single-player-only and story-centric game which has most of its gameplay mechanisms convincingly within the strategy game genre, which has long forayed into the realm of multiplayer experiences.

However, Katauri Interactive is one such game-maker. It would be one to carve out a niche for itself (as is evident by Katauri and 1C Company cranking out expansion after expansion and “gold” editions of King’s Bounty).

King’s Bounty: The Legend has some issues – some of which occur even before the player starts playing the game proper. Yet, they are not too severe enough to overshadow the strengths and appeals of the game.

SOME SETTING ISSUES:

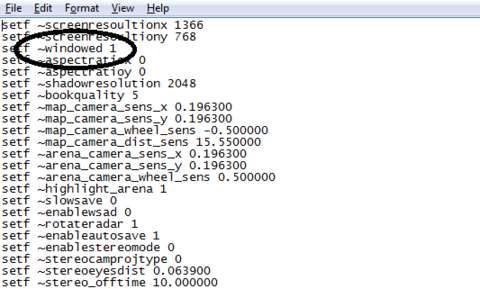

Before starting the game, the player may need to do some wrangling with the files for the game. This is because the game lacks in-game features for changing the technical settings of the game.

For example, there is an option to play the game in windowed mode instead of full-screen, but the in-game settings menu and even the manual would not inform the player that it is there.

PARTIALLY-IMPLEMENTED SCREENSHOT FEATURE:

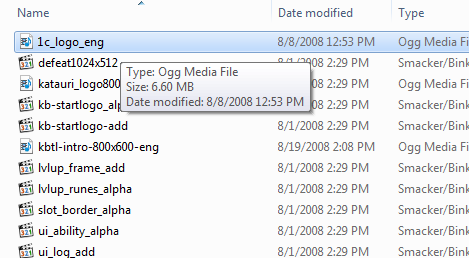

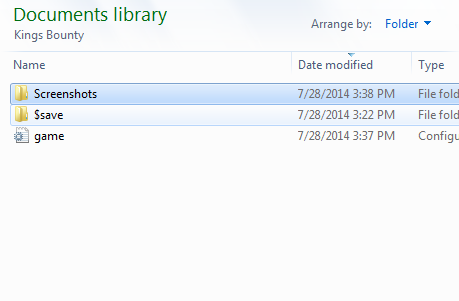

The demo version of King’s Bounty: The Legend has a feature which allows the player to take screenshots at any time during the game. The screen captures go into a folder which resides in the “My Documents” directory (at least for the Windows version of the game).

It is not certain whether this feature was supposed to be in the launch version of the game. There is nothing in the manual which refers to it.

Yet, pressing the “Print Screen” button would raise the “Screenshot Saved” notification, except that the screen capture would go nowhere by default.

To get this feature working, the player would have to fiddle again with the directories for the game.

PREMISE:

After having set up whatever the player thinks is necessary for his/her experience with the game, he/she can start playing the game – and experience the stiltedly presented introduction to Katauri (or rather, 1C’s) re-envisioning of King’s Bounty’s canon.

After a lot of exposition (which in hindsight was actually foreshadowing for an expansion pack), the player is introduced to his/her player character (which he/she would have picked before said exposition). He is a fresh graduate of the School of Knights of the Kingdom of Darion.

The player character does have a backstory of his own, but one that would not matter much in the story because he would be sent off on quests which eventually escalate to the usual save-the-kingdom story trope.

King’s Bounty: The Legend won’t be telling fresh stories, but what it has is enough as an excuse for its surprisingly deep gameplay.

PLAYER CHARACTER:

Although the player’s choice of a profession is not really important with regards to the narrative of the game, it is important to the player’s chosen play-style. Each of the three classes comes with a description which is mostly apt.

A player who has played a few playthroughs of The Legend would know that none of them happens to be particularly disadvantaged against the others.

The Warrior is the one who can field the biggest army and can unlock the special abilities of certain units, but his advantage comes with the setback of frequent recruitment.

The Paladin is a hero who has skills which bypass certain limitations on unit morale, thus allowing the player to field unlikely units in his army, e.g. skeleton archers fighting alongside dwarfen cannoneers.

The Wizard starts with the devastating Fireball spell and can learn and use more spells in battle than the other two, which makes him appealing to players who like more options in combat.

SKILL TREES:

Despite what has been said earlier about the three different professions, all three of them have access to the same skill trees; only a few skills are the exclusive purviews of the different professions. However, each hero’s progression would be mainly invested in the skill tree which is associated with his profession because of the resource system of runes, which will be described later.

Anyway, veterans of the RPG genre would know how the skill trees and their nodes work. The skills which the hero gets are mostly passive skills, such as those which unlock mana regeneration during combat or unlocking the special powers of certain units.

However, some skills have very situational benefits which reduce their utility. For example, one of the ‘Mind’ tree’s penultimate nodes allows the player to promote Priests into Inquisitors, but this is only useful to players who actually use Inquisitors. (They are mainly support units.)

If the player does not favour these skills due to his/her chosen playstyle, these nodes are all but useless. Unfortunately, their level 1 variants tend to be prerequisites for more desirable skills, thus the player is forced to spend precious runes on them.

The skill trees would have been better designed if the hero’s level is the only prerequisite.

RUNE RESOURCE:

Typically, there is a character progression system in RPGs in which the player character is granted some points to spend in capabilities and other statistics. The Legend makes use of a variant of this system and partially converts it into a resource system too.

Every level which the player gains grants him/her several runes to spend in the player character’s skills. There are three types of runes: Might, Mind and Magic, code-coloured red, green and blue respectively.

For obvious reasons, each hero gets more of one type of rune than the others for every level gained. Incidentally, this also makes it possible for the hero to complete his associated skill tree in a play-through.

Inexplicably, there are runes which can be found in the game world. There are runes floating around, their small sizes given away by their particle effects and rotating animations. On rare occasions, runes can be found even on the battlefield (within treasure chests).

It is in the player’s interest to get as many runes as possible, even runes of the types which are not associated with the hero.

TUTORIAL:

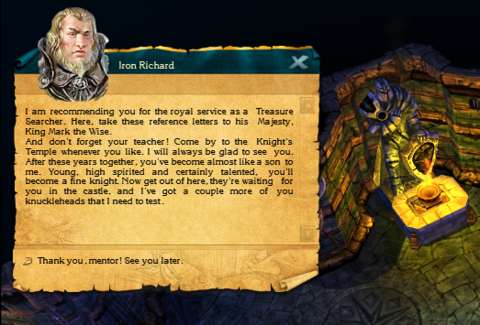

The Legend has an optional tutorial for the player to peruse; it is disguised as the graduation test of the player character, and one which is literally a do-or-die.

From the perspective of practicality, the tutorial only gives lessons on the game mechanics; the player has to look at the manual (as all game consumers should) for things such as controls. If there is any issue with this, it is that things such as controls are not shown in-game in the options menu.

The main appeal of the tutorial is its humour. The player character is hardly the first graduate of the School of Knights, and not the first prodigious one either. The tutorial also sets up the kind of humour which the player would see throughout the game, namely the self-awareness of the characters about who and what they are and what they do for a living.

ARMY SLOTS:

Like the earlier Heroes of Might & Magic games, the hero is little more than a stack of bonuses and magical support for the player’s army, which is the one doing most of the heavy lifting.

However, the player has only 5 slots for unit stacks. Veterans of the Heroes of Might & Magic games would not be surprised, but the fact is that the hero’s army will frequently be outnumbered in terms of stacks.

A unit stack’s army slot also determines where it appears when a battle commences. The problem here is that the unit stacks start out adjacent to each other, which makes them vulnerable to area-effect spells. Due to this problem, the “Tactics” skill is a must-have.

The army slot system is further limited by another game mechanic in the game, which is “leadership”. It will be described shortly.

LEADERSHIP:

Even if the player has found sources of units, e.g. places to recruit units from, the player cannot just spend away gold to amass a considerable army to steam-roll mobs with.

This is because such intentions are held back by the game mechanic of “leadership”. This game mechanic is explained away as the player character’s inexperience at leading armies. Anyway, the “leadership” rating of the hero is a statistic of its own.

Leadership determines how big a unit stack can get. To be more specific, every type of unit has a leadership “cost”, which is summed up when a player scrapes together a stack of that unit. The total “leadership” cost of the unit stack cannot exceed the hero’s leadership rating.

This limitation is also extended to any one type of unit. In other words, the player cannot have two unit stacks of the same type of unit and expect each of their total leadership costs to reach the hero’s rating. They must sum up to the hero’s rating instead.

This can lead to some wrangling, because low-tier units do not have leadership costs as high as those of the more powerful ones. Using the more powerful units always give the impression that the hero’s leadership is not being efficiently utilized.

However, choosing to use lower-tier units or higher-tier ones is a matter of preference. All the player needs is an army which caters to his/her favoured strategy at the time.

As an illustrative example, Dragons are more favoured for their ability to strike early in a battle and move about quickly. However, massive stacks of low-level units, such as Skeleton Archers, with the same leadership costs can do consistently more damage than equivalent stacks of Dragons.

FREEBIE UNITS:

When the game loads a map, it makes secret rolls for each independent mob of units which is moving about the map. These rolls determine whether the unit would be ambivalent or hostile towards the player character.

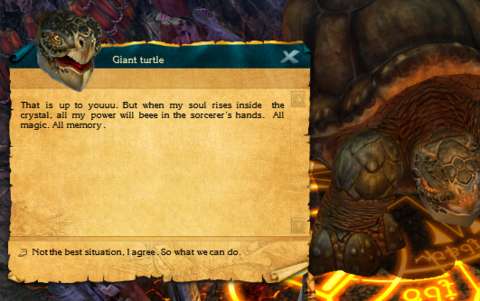

Ambivalent mobs generally remain so. These mobs move along their patrol paths, completely ignoring the player character. Some of these mobs can actually be approached, giving the player an opportunity to recruit them into the hero’s army. An example is shown in the earlier screenshot.

The player generally cannot recruit units from hostile mobs, but some hero skills allow the hero to inveigle some of the opposing mobs’ units over into his/her own army.

As lucrative as these “free” units may seem, they reveal a flaw in the otherwise tightly designed leadership system.

INSUFFICIENT LEADERSHIP:

Although the game has systems in place to prevent the player from creating a unit stack which exceeds the hero’s leadership rating, there can still be occurrences where the player can get such a unit stack. Unfortunately, the game’s contingency scripts for this possibility are rather lackadaisical.

This possibility can occur when the player recruits units from mobs and these units join one of the player’s existing unit stacks, thus bringing the total leadership cost of the stack to over the hero’s leadership rating. When this happens, the stack’s morale indicator is replaced with an ominous-looking one.

If the player goes into the next battle with that stack of units anyway, it has a very high chance of going out of the player’s control when its turn comes up. Considering that the unit stack starts very close to the player’s other unit stacks, this mishap is very much undesirable.

To prevent this from happening, the player has to dismiss the excess units or split stacks and stash the excess units away in garrison slots. However, the latter measure reveals another problem with the game.

SPLITTING STACKS:

There are few occasions where the player needs to split stacks. This is fortunate, because the system for this is terrible.

Firstly, the player has only five army slots to work with, as mentioned earlier. More often than not, the player will need to have all five slots filled in order to have the variety and quantity of soldiers which are needed for battles. Therefore, the player will need to visit castles with garrisons often in order to make use of their garrison slots to facilitate stack-splitting.

However, there are only so many castles with garrison slots in the game, and remembering where the player has stashed units is not fun. Replenishing unit stacks from garrison slots is also a bother, because there does not appear to be any accommodation for splitting between stacks in garrison slots and stacks in the player’s army slots.

Oddly enough, Katauri Interactive has thought of closing a loophole regarding stacks of the same type of unit, as mentioned earlier. Yet, it overlooked this design flaw.

DISMISSING UNITS:

As mentioned earlier, the only other way to deal with overflowed unit stacks is to dismiss the excess units. However, this is not the most optimal of solutions, because units are virtually limited in supply throughout the entire game. Even if the player may have come across a recruitment source which has thousands of units, it only has those thousands, which can be squandered away if the player is rather cavalier.

RECRUITING UNITS:

Speaking of recruiting units, the player will be doing this a lot. This activity is also one of the flaws of The Legend – the entire King’s Bounty series so far, in fact.

The player can recruit units for his/her army at castles or other structures which appear to be capable of accommodating people, animals or other creatures. These are usually depicted by castle icons which replace the mouse cursor when the player examines them. The player can also hold the right-mouse button to check these structures’ descriptions; if it implies that someone or something can live in them, these are usually sources of units too.

Once the player has found sources of units which he/she would like to have in his/her army, the player has to make a mental note of where it is. This is because he/she will have to return to it to restock as frequently as he/she loses units in battle.

The player can mitigate this tedium by keeping casualties to a minimum, but the game could have been better if it had more convenient means of recruiting units.

It does try to have one through the concept of eggs and seeds; the player can “recruit” units by hatching eggs or germinating seeds in the hero’s inventory. However, the number of units which the player gets is randomized, and sometimes, even the type of unit is randomized. This vagary of luck makes eggs and seeds quite unreliable sources of units.

Furthermore, when the player no longer wants to use a certain unit, he/she would have to decide on what to do with the unit stack. Dismissing them is not wise, because supplies of units are very much limited in King’s Bounty, and stashing them somewhere requires the hassle of finding some garrison slots to put them in.

All this tedium of recruiting and stashing units can make the gameplay of King’s Bounty: The Legend seem repetitive.

UNIT STATISTICS:

Like Heroes of Might & Magic, Disciples, Age of Wonders and other games of their ilk, King’s Bounty has units whose performance is measured by their statistics. Most of these, such as Attack, Defence and Damage, would be familiar to veterans of such games.

In fact, they may as well have been lifted whole-sale from Heroes of Might & Magic. To cite an elaborative example, the Attack, Defence and Damage statistics work together to determine how much damage which a unit stack can do to its target: if the attacker’s Attack rating is higher than the target’s Defence, the former gets a multiplier bonus to its damage.

PROTECTION/WEAKNESS:

King’s Bounty also makes use of a resistance/vulnerability system, albeit naming it “protection/weakness”.

The manual implies that this system is applied before damage calculations with the Attack and Defence statistics, but it is not exacting in its details either.

Making use of this system is of importance to a player who uses magic in combat. However, the game is not exactly very helpful in assisting the player in doing this.

The damage type which a unit inflicts is depicted by a tiny icon next to its damage statistic (which is presented with text that is already quite small). Again, the player would need to look at its tooltip, because the icon is too small for quick recognition.

LOOSE ITEMS:

As the player explores the game world, he/she would notice that there are loose items lying around waiting to be picked up.

These include runes, which have been mentioned earlier. There are also banners, which are items which increase the leadership rating of the hero for no particular reason. There are also magic crystals, which are used in learning and upgrading spells as well as utilizing certain magical items; there will be more elaboration on this later.

The game goes a long way to make these items easy to spot; they have quite a lot of particle effects and flashing glyphs around them.

SPELLS & MANA:

Regardless of the player’s preferred playstyle, he/she is likely to end up using a spell sooner or later during a battle. This is because some spells have too much utility to be overlooked, for better or worse.

Spells are fuelled by mana, which the hero generates automatically outside of battle; the player can also take skills which generate mana during battle (and this would be a wise decision). There are also other means of getting mana, one of which involves the use of a rather queer and risky spell (that is, Magic Spring).

Casting a spell usually involves having to watch the animations for the spell, which can be elaborate and a bit long at times; the spell Ice Snake is a particular example.

The spells include the usual gamut of buff, de-buff and direct-damage spells, as well as combinations of these three. To reuse an earlier example, the (oddly named) Magic Spring is a buff which grants a small defensive bonus onto a unit stack, which in turn gives the player mana when it is attacked.

Spells can be learned by using scrolls; the game rationalizes this by saying that the player character is ‘copying’ the instructions for spells from the scrolls into his spellbook. Yet, for whatever reason, this requires the expenditure of magic crystals. However, learning new spells is affected by a peculiarity of the system which is used for the storage of scrolls; this will be described later.

Spells can be upgraded with the expenditure of magic crystals. Upgraded spells are more powerful but cost more mana. The player can use lower grades of spells, but this feature happens to reveal a gap in the game’s documentation.

ISSUES WITH SPELLS:

An observant player may notice that there are some problems concerning spells; these problems affect user friendliness and gameplay balance.

The ones which affect user friendliness are the lack of documentation for some gameplay features.

The biggest of these is that the manual and in-game documentation do not mention anything about the control inputs to cast a downgraded Level 1 or Level 2 version of a Level 3 spell. (This can be done by holding down “Ctrl” or “Shift” respectively.) This information is apparently only available through the forums for the game.

There are also lesser documentation issues. For example, the spell “Slow” has an undocumented secondary effect of lowering the target’s initiative for the current turn in which it is cast. Another example is that the spell “Bless”, which maximizes the damage output of a unit, only works on regular attacks.

Most spells are designed for gameplay balance. For example, spells would never achieve the raw damage output of massive stacks of units, but they bypass the defence statistics of units.

However, one of the spells happens to work around a design for gameplay balance. This gameplay balance design is a hard-cap on the mechanism of the utilization of differences between an attacking unit stack’s Attack rating and the defending unit stack’s Defence rating.

The spell Dragon Arrows does not circumvent this design, but it does destroy the parity between bow-using units, of which there are four. Since the spell simply grants such units ammunition which ignores the target’s defence rating and the aforementioned hard cap is still in effect, the Skeleton Archer is simply the best bow-using unit to use with Dragon Arrows because it has a better damage output to leadership cost ratio compared to the other bow-users.

The least significant issue about spells is that there is a lost opportunity to have spells which are cast outside of combat. For one, it would have been convenient if the player can cast spells which set up portals between two lands.

SCROLLS:

The player may not always have the mana to cast spells. If the player does not cast spells in a turn, he/she would have wasted an opportunity to turn the odds (further) in his/her favour in the battle.

Fortunately, there is the feature of scrolls. In addition to being used for the learning of spells, scrolls are also used to cast spells with, but without the expenditure of mana. The player is restricted to just level 1 versions of their spells, but casting spells from scrolls is better than doing nothing while the hero is regenerating his mana.

Ostensibly, the hero can only keep a limited number of scrolls; certain items and skills allow the hero to store more. However, this limitation appears to have been circumvented with regard to scrolls which the hero picks up either as loose items, as quest rewards or through using the special abilities of certain items. Getting scrolls this way allows the player to keep more scrolls than he/she should.

However, this comes with a consequence. The player cannot buy scrolls from merchants as a result. This can be frustrating, if the player is interested in having the hero learn new spells and there happens to be scrolls for these on sale.

UNIT TRAITS:

Many units happen to have capabilities which are always available to them, either through their vocation or their nature.

Making use of these traits can be of great help in battles. For example, knowing that Griffins always retaliate upon being attacked means that the player can attempt to make use of Griffins in meat-shield strategies.

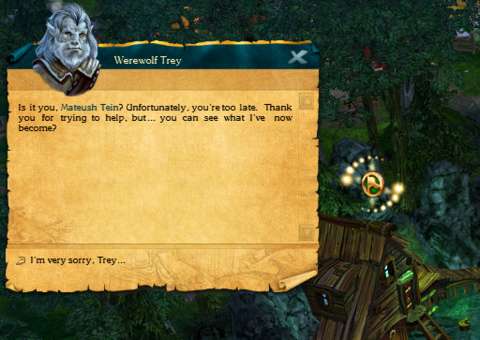

However, the documentation of these traits is affected by some translation issues; an example has already been shown in an earlier screenshot.

The most severe of these issues is the “Archer” trait, which is given to any unit with a distance-determined ranged attack. Veterans of Heroes of Might & Magic would recognize this as the “Shooting” trait, but less-experienced players may confuse this trait with units which use bows.

Another trait which is not so well-documented is the type of terrain which a unit is associated with. This can be known by examining the backgrounds of unit portraits. For example, demons are usually associated with hell-blasted or volcanic terrain, and the backgrounds of their portraits show this accordingly. However, this is not mentioned in the manual.

UNIT SPECIAL ABILITIES:

Many units happen to have special abilities, which act a lot like spells. For example, Priests have their own version of the Blessing spell, which may help in certain strategies involving having a main damage-dealer.

Proper use of these special abilities allows the player to win battles. For example, the Inquisitor’s Holy Wrath ability, which is practically the upgraded version of the Priest’s Blessing, grants the player Rage points, which allow the player to make use of Chest of Rage abilities (more on these later).

Most special abilities can only be used once or twice before they cannot be used anymore during the course of a battle. For the more tactically useful abilities, this is understandable, such as the common “Running” ability which melee-oriented units usually have.

However, the limited charges for other lesser abilities are not so justified. An example is the dwarfen Alchemist’s special potions and bombs, which can only be thrown once for not exactly a lot of damage.

Some other special abilities can be used again after a few turns. These are usually mundane special abilities, such as extra-damage attacks.

However, for whatever reason, some powerful special abilities have such rules instead of limited charges, which would have made for better gameplay balance. For example, the Emerald Dragon has a grapple ability which allows it to make an attack which cannot be retaliated against; after using it, it gets to use it again after two turns.

GEAR:

King’s Bounty actually started as a spiritual predecessor to the Heroes of Might & Magic series, so the player can expect some similarities to the better known Heroes of Might & Magic in The Legend.

The most obvious of these is the system of gear for the hero. He has some slots for familiar equipment such as armor, headwear, belts and, of course, weapons and staffs. The items which fill these slots convey understandable and familiar benefits: for example, weapons typically increase the hero’s Attack rating and plate mail increases Defence.

However, The Legend introduces some peculiarities to some gear pieces, especially the more powerful ones. These will be described shortly.

SPECIAL PROPERTIES OF ITEMS:

Certain items do more than just sit in the hero’s item slots and increase his statistics, or that of the units in his army.

Firstly, the hero can interact with some of these items, and in the narrative sense too. This can usually be done with quest items. This is a surprise, because in games with RPG elements, quest items tend to be little more than MacGuffins which do little other than take up space in the player’s inventory.

Other than benefits such as the one shown in the previous screenshot, “using” items provides benefits such as refilling the hero’s mana reserves or rage pool (more on this later). Some also provide scrolls, in return for magic crystals.

There are items with even more esoteric properties. For example, there is a toy castle which allows the player to enter another place from anywhere and explore it.

There are also sentient items, with which the hero can strike conversations with, usually to know what they can do.

Speaking of sentient items, there are powerful pieces of gear which do not unconditionally grant their benefits. There will be more elaboration on this shortly.

ITEM MORALE:

In King’s Bounty’s world, powerful items tend to become so powerful that they develop personalities of their own. Although most of them are not entirely sentient, they can still choose to hold back on their benefits if they choose to (usually because they have become disillusioned with their owner). This willingness of items to grant their properties is measured as item “morale”.

Some items have likes and dislikes, which are described in the information screens for the items. For example, there may be an item which despises undead. If the player destroys undead while using it, its morale is increased. Getting the morale of an item high does not provide any tangible benefits though.

However, when an item’s morale plummets to zero, it withholds its benefits. The player either needs to do things which it likes to get on its good side again, or fight its keepers to forcibly regain control of the item. There will be more elaboration on battles with Keepers later.

ITEM INFO:

Most of the time in fantasy games, the descriptions for items tend to be quite text-heavy. However, those in The Legend have some presentation which is out of the norm.

Some items have images which come together with their text. For example, there are painting items which come with images that are actually concept artwork for the game. Some of these images also have more practical uses, such as maps to treasures.

UPGRADING ITEMS:

Upgrading gear pieces is nothing new in video games. However, where in other games the player has to gather the necessary materials, pay the costs of upgrade and/or perform some task, the player usually has to fight enemies within pocket dimensions.

This game feature ties into another narrative about powerful magical items. Some of these items are held back by mischievous gremlins, who are messing up their functions. However, the game also suggests that some items deliberately withhold their benefits and wait patiently for the hero to put in effort to force them to yield. It is not clear which is the actual reason, but this is just a very minor narrative issue.

Anyway, once the player has defeated its keepers (more on these later), the item is upgraded into a higher form. Conveniently, the player can see the various forms which an item has in its tool-tip.

SPOUSE:

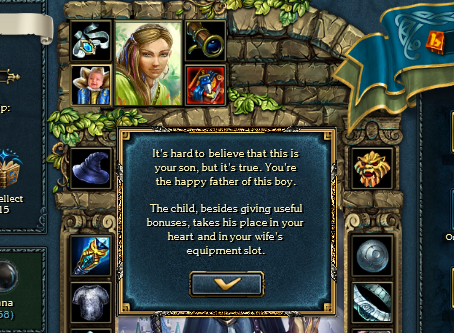

One of the most hilarious, yet most annoying, features of The Legend is the opportunity to obtain a companion – specifically a wife for the hero.

Throughout his travels, the hero would come across several women, most of whom ascribe to typical tropes about fantastical ladies. The player will know that they are potential spouses because the hero would make statements suggesting that he is quite smitten with them. If the player chooses to have him do so, he would attempt to woo them, though this of course typically requires the completion of tasks.

After winning the heart of his wife-to-be, she joins him on his travels, essentially becoming a minor hero(ine). She grants some bonus points in a statistic or two, and also has some item slots.

Interestingly, different ladies have different item slots. For example, the frog princess has more artifact slots than the other ladies.

The hero’s spouse does not just act as a holder of items though. She can also produce babies, if the player chooses to have the hero share some intimate moments with her (these moments are not visually depicted at all, of course).

Some time after a fling, the spouse births a baby. Oddly enough, this baby acts likes an item, granting the player considerable bonuses which can rival some powerful items.

However, the baby is practically a permanently equipped item. Therefore, the player will have to weigh the strengths of having a baby against keeping the spouse’s item slots clear.

Certain ladies have additional abilities, though they are not always readily available for use. For example, the aforementioned frog princess can turn into a frog, given enough time of neglect. When this happens, her bonus of additional Intellect points is replaced with bonuses for swamp-based creatures.

As another example, there is a lady who can switch between a mortal woman and an undead one at the player’s command, any form providing very different bonuses than those of the other.

The player can choose to have the hero to divorce his spouse at any time, if the player has grown tired of her (for reasons which will be described shortly). However, doing so is not without significant costs – the spouse takes her babies with her and due to laws which the hero obeys, half of his money too. She is also gone forever.

The main problem with the feature of spouses is that after having married them, their entertainment appeal plummets. They no longer have any further quests associated with them, and they do not contribute much to the main story either. They become little more than tools after marriage, albeit tools which are difficult to dispose of due to the drawbacks of divorce as mentioned earlier.

(Incidentally, the feature of spouses was toned down in later King’s Bounty titles, likely because of how trivially it treats marriage.)

BATTLES – OVERVIEW:

Fighting battles is what the player will be doing the most in the game. In fact, just about any obstacle to the advancement of plots involves a battle. There are always villains with armies barring the hero’s way, often outnumbering the hero’s own, so the player will have to learn how to conduct battles efficiently to minimize losses and waste less time going to and fro recruiting units.

Interestingly, there are a few types of battles, often dictated by the hex-gridded battlefields which the player would fight on.

HEX GRID:

Speaking of the battlefields, they are made up of hexagonal elements. Thus, each unit stack on the battlefield can face and attack enemies in one of six directions in melee combat, and conversely, any unit stack can be surrounded by up to six other unit stacks.

Virtually all unit stacks occupy just one hex each, even for large units such as giants and dragons. This is convenient. It so happens that the hexes are large enough to accommodate even the models of large units without causing adjacent models to clip into each other, which would have been unsightly.

Obstacles on the battlefield, which are placed virtually randomly, also happen to occupy hexes. Utilizing these obstacles to create chokepoints is crucial to prevailing against superior armies. Indeed, this is one of the best and most satisfying nuances in the game.

LOW & HIGH OBSTACLES:

Making good use of obstacles wins battles, but the game does not make it clear what kinds of obstacles there are on battlefields.

There are actually two types of obstacles: “low” and “high” obstacles. “Low” ones are visibly low-lying obstacles, such as piles of rocks. They prevent movement by units which move around on foot, but they will not stop units such as ghosts and dragonflies which simply flit over them.

It is not clear which obstacles are considered “high”. This is made more of a problem due to translations issues, such as the aforementioned ghosts and dragonflies having the “Soaring” trait, a more appropriate substitute for which is “Hovering”.

Although some of these obstacles are obviously “high”, such as pillars that reach into the air, there are others such as big tree roots which are far lower in stature but are considered “high” obstacles. The player will often have to learn the hard way which obstacles are “low” or “high”.

MOVEMENT ABOUT BATTLEFIELD:

The player will be moving units on the battlefield to have them claim advantageous positions and/or stay out of the enemy’s reach. The game has some conveniences, such as showing the routes which the unit stack would take. The player cannot specifically dictate the route which units would take, however.

The speed of the unit determines the number of hexes which it can move through before having to end its turn. This number of hexes is called in-game as “Action Points”, which is not exactly a good choice of nomenclature considering that there are games such as the Fallout series which have more understandable reasons for using such phrases.

A special mention here goes to the surprisingly good automatic scripting for the route which units with the “Charge” trait would take when attacking an enemy. These units, such as Horsemen, will spend their remaining Action Points to gain as much distance as possible from their enemy before making a charge.

Unfortunately, there may be an issue in how the game informs the player about what kinds of movement which a unit would take, if it has more than one type.

Granted, most units have only one type of movement, such as romping around on the ground or hovering in the air. However, Dragons have two options, and because they are some of the most tactically useful and powerful units in the game, this ambiguity can be an unpleasant problem for inexperienced players.

Observant players would notice that dragons usually use their capability of flight to move about, which given their high speed and initiative, means that few enemies can keep out of their reach. However, if they are ordered to move just two hexes to anywhere, they opt to move on foot instead.

Perhaps Katauri Interactive intends to make use of all the animations which it has made for Dragons, including those for their awkward walking. Yet, although these animations are amusing, they do come with tactical consequences. For example, the Dragons are vulnerable to spells such as the “Trap” spell when they move around on foot.

Of course, a more forgiving player would say that all these so-called problems about the movement of Dragons are nuances which should be lauded, but that is cutting Katauri Interactive a lot of slack for its lack of documentation on these designs.

At least the game is quite obvious in showing that Dragons stand on their feet when they end their movement. (This means that their onslaught can be stopped if the player can predict where they might land and rig that with a Trap spell.)

INITIATIVE:

A system of “initiative” determines when a unit stack would be able to take its turn during a battle. For this purpose, each unit type has an initiative rating. A higher rating means that the unit would be able to move earlier than the others (whether these are in its own team or not).

In the case of ties in the initiative ratings of multiple unit stacks on both sides of the battlefield, which of these would get to move first is randomized. (The computer-controlled opponent may have the RNGs rigged in its favour, though this is difficult to prove without extensive statistical tests.)

For better or worse, Dragons tend to be able to go first. Considering how powerful they are, the army which happens to have Dragons tends to already have an overwhelming advantage over those which do not.

The most important nuance about initiative is that a hero can only fire off spells when the turn of any of his/her/its own units come up. This means that having a unit stack with very high initiative lets the player fire off spells earlier, which is often a critical tactic. Forcing enemy unit stacks to give up their turns, such as setting them to sleep, is also another example.

RANGED ATTACKS:

There are many units with ranged attacks; these have the aforementioned – and still poorly named - “Archer” trait.

Anyway, units with this trait have effective ranges which appear to be dependent on their unit level; the range in which their attacks would do full damage is four hexes times their unit level. However, this is not told to the player within the documentation of the game. However, the game does mention that having a unit shoot beyond its effective range causes it to inflict only half of the raw damage which it can do.

There are a few units with traits which ignore this limitation of range, such as units with the Sniper trait like the Elf Archer. There are other such traits, such as the magical ones associated with mage-type units, but this is not mentioned clearly in the descriptions of these traits.

DAMAGE CALCULATIONS:

The game makes use of the differences between the Attack rating of the attacker and the Defence rating of the victim to calculate damage, as mentioned earlier. It also makes use of RNGs to roll on the damage range of a unit type, which might not please players who despise having luck as a factor in gameplay.

Conveniently, the player can choose to have the game show the RNG rolls and the calculations behind the damage output of unit stacks.

STRUCTURES:

In addition to obstacles on the battlefield, there can be structures which take up space on the battlefield, thus acting as additional impediments to movement. Incidentally, they are always counted as “high” obstacles.

Some of these are already on the battlefield, acting as unaligned structures which either buff or smite any unit stack which comes within their range. Their range of effect is visible when they are examined, so a cunning player would be able to make positioning decisions to maximize their utility. However, these structures can be fickle, especially those which can bestow either a buff or inflict a de-buff.

Then, there are structures which the player can place down. These are generally associated with the Chest of Rage gameplay feature, which will be described later.

TREASURE CHESTS:

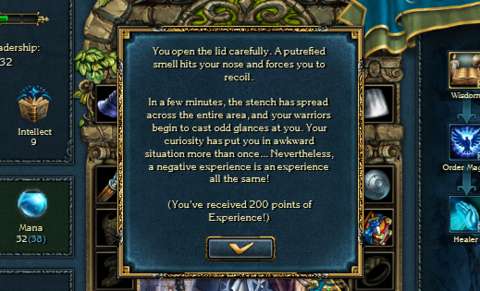

For whatever reason, some battlefields have treasure chests lying around, complete with alluring glows.

These treasure chests pose an element of risk-versus-reward for the player. These chests may have gold coins, scrolls or best of all, runes. However, this requires the player to spend the actions of unit stacks to go after them, which is not the wisest of decisions if there are enemies which threaten the player’s units.

Furthermore, the computer-controlled opponent will sometimes open these chests too, practically denying them to the player; the player will not be able to loot their contents off defeated opponents.

Incidentally, treasure chests are considered to be obstacles too, and can be used in the players’ strategies if he/she favours chokepoint tactics. This is a very satisfying gameplay nuance.

There are some units which have special abilities that make use of treasure chests. Chief of these is the Marauder, which can teleport over to any hex next to any treasure chest on the battlefield. However, the presence of treasure chests is not always assured, so the Marauders are units of highly situational value.

(In fact, it is of more use to computer-controlled opponents, who will make use of these chests for some unpleasant offensive moves.)

BOSS BATTLES:

Katauri Interactive apparently does not have any severe reservations about spoilers, because boss battles happened to be documented in its manual, of all things.

As the manual suggests, boss battles are quite different from the usual battles which the player fights. The opponent is not an army, but a colossal creature with thousands of hit points and immunity to many spells and status effects.

A boss is also always capable of retaliating, so the player should not expect to be able to take advantage of his/her numerical superiority.

Besides, bosses are not always alone. Most of them toss new unit stacks into the battlefield every turn, seemingly unceasing until the player’s own army is overwhelmed. The player must learn to divide his/her attention between the boss and its cronies.

There is an issue with boss battles though; the Rage system does not work for them, and for no discernible technical reason.

KEEPER BATTLES:

As mentioned earlier, the player can subdue wayward magical items or upgrade them by fighting its “keepers”. These battles occur within otherworldly pocket dimensions.

The keepers of an item are gremlins standing on top of powerful towers, and they are usually accompanied by unit stacks of types which vary according to the nature of the item. For example, items which are associated with the elves usually have elven units defending the gremlins.

Battles with keepers are made difficult by the presence of these gremlins, which stand atop powerful towers. Due to translation issues, the two types of gremlin towers are called “evil” and “friendly” gremlins.

The “evil” ones mainly toss offensive spells at the player’s units, whereas the “friendly” ones summon in reinforcements either as new stacks or to increase the number of existing ones. Either type of tower can choose to cast buffs instead.

It would not take long for an observant player to realize that knocking out the towers as early as possible is critical to winning battles with keepers.

The appeal of battles with keepers is that they can (generally) be initiated at any time through the player’s inventory system. This is convenient, if the player is looking to grind for experience or for Rage points (more on these shortly).

CHEST OF RAGE - OVERVIEW:

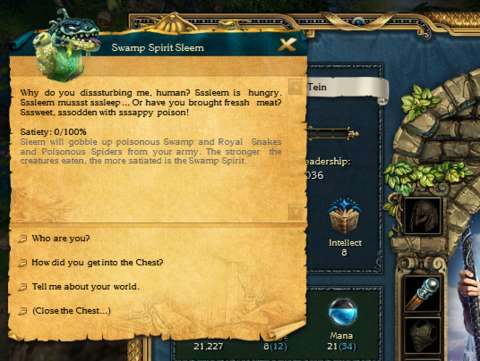

Some time into the story, the hero has an incident where he gains the servitude of a quartet of powerful entities (called “spirits” in-game). These entities are powerful creatures, but initially have no respect for the hero.

Typically, the player has to appease these entities by doing favours for them, at least until after they actually talk with the hero. Speaking of which, talking with them can only be done after the hero has obtained several levels and completed some main story quests; the game does not make these requirements clear.

Some of these favours can be readily done, such as those for the Scragg entity and the anti-mage living weapon. The other favours can only be performed some time into the story.

Afterwards, the entities grant the use of “Rage” powers, which have benefits which are virtually unique. However, not all of them remain competitive later in the game.

RAGE POOL:

According to Katauri Interactive’s canon of King’s Bounty, strong emotions, especially rage, have great power, especially to the demonic and their artifice. The Chest of Rage is one such demonic artifact.

The hero can accumulate rage through a few ways. The main way to do so is through battle: when the player’s unit stacks inflict damage or take damage, the hero gains a few rage points. The difficulty setting which the player has selected also determines the player’s net gain.

Speaking of gain, Rage gain through the exchange of damage between unit stacks is further modified by the Hero’s maximum Rage pool; if he has a higher maximum, he gets more Rage. Incidentally, using Rage powers only consume specific amounts of Rage points, so it is in the player’s interest to get a Rage pool as large as possible in order to obtain more tactical options.

There are other ways to gain Rage, the rarest of which is to drink from fountains of Rage. These fountains do eventually replenish, but only what seems to be hours.

Certain items also provide specific amounts of Rage points, but these are precious few things which can be wasted quite easily if the player is not wise about their use.

RAGE DEGRADATION:

Unlike mana, rage eventually dissipates. Even with some special items which slow down degradation of Rage, the player would be hard-pressed to maintain the hero’s Rage pool. Consequently, the player is encouraged to bounce from battle to battle in order not to waste Rage.

Interestingly, the degradation of Rage is tied to the regeneration of Mana. This is not explained clearly in game, but there are enough in-game and story-based hints to suggest that as sources of wondrous power, mana and rage are diametric opposites. As long as the hero still has some Rage, mana regenerates slower.

RAGE POWERS:

As mentioned earlier, Rage powers have effects which are not replicated by anything else in the game. Consequently, the use of Rage powers is a clear advantage which the player has against any opponent.

The entities which the player can enlist earlier than the others are Sleem the Scragg and Kerock the Living Weapon. The Scragg has some poisonous powers whereas Kerock’s powers are mostly about inflicting extra damage on mages.

Unfortunately, the damage-dealing powers of both creatures rapidly become less competitive as the playthrough progresses. Considering the amounts of Rage which they consume, they do not inflict enough damage to be worthwhile.

However, they do have a few abilities which remain tactically useful even late into the game, if only because they stall the enemy.

Sleem has a shield which it can grant unto any friendly unit stack, but it disables the stack’s retaliation attack and prevents it from moving. Yet, regardless of how weak or strong it is, it will absorb at least one hit. This can be used to trick opposing unit stacks into wasting their attacks on the shield. The shield also appears to be unaffected by area-of-effect spells which the player casts, so this can be used to protect a unit stack used for baiting.

Kerock can raise a wall of rocks three hexes in length. It is not long enough to completely block enemy stacks, unless the player places it at chokepoints, but that is not its true worth. Due to the limitations of the scripts which control the decision-making of computer-controlled opponents, enemy unit stacks may choose to go around the wall, which wastes their turn. They can of course crash through the wall, but this also wastes their turn anyway.

Lina the ice savant and the Reaper of Time are the next two entities to help the hero. Lina’s powers are the most peculiar, if only because they vary greatly in usefulness.

There is the highly situational Ice Ball, which is powerful but rather difficult to use due to its rolling movement. The ball is only useful against static or enemy stacks which have spent their turn. (Incidentally, it has very low initiative, ensuring that it moves last – which is actually for the better.)

Then there is Lina’s drone, which either heals a friendly unit stack or zaps an enemy-owned one. It cannot be brought down in any way, but in return, the player has no control over what it decides to do.

Next, there is Crown of Ice, which is Lina’s most useful ability and which has been shown in an earlier screenshot. It places a cluster of fragile ice on the battlefield; despite its fragility (it can be destroyed with any attack), it is considered as a high obstacle and can stall numerically superior enemies.

Lina’s most unreliable power is Chargers. She drops orbs of mana and rage onto the battlefield at completely random locations; worse, the enemy can pick these up to deny them to the player and gain an action point from them too, just like the player’s own units can.

Supposedly, Chargers can be upgraded such that they drop closer to the player’s own units, but they still drop in random directions anyway.

Finally, there is the Reaper. Its powers are the only ones which remain competitive throughout the game. Indeed, its very first power, Soul Drain, does percentage-based damage, meaning that it is useful against any unit stack. Its next power has less potential damage output, but it is the only Rage power which actually lets the player gain more Rage.

The Reaper’s Time Back resets the position of a unit stack to where it was before it made its move, making this very useful to bail out powerful first-strike units (e.g. Dragons) with after they make their devastating early-battle attacks. The Reaper’s final power hits every enemy stack on the battlefield for significant damage.

Perhaps the other entities would have been more useful if they had been designed with late-playthroughs in mind. Granted, they could be upgraded to be more powerful, but they are often not worth the Rage spent anyway.

(Curiously enough, the Chest of Rage feature is missing from later games in the King’s Bounty series, or at least not wholly replicated.)

RAGE COOLDOWN:

Even if the hero has the Rage to summon the entities, they are shackled creatures who are no longer as powerful as they once were. After using any power, an entity has to rest for at least one entire turn, during which he/she/it cannot be called upon for aid. Indeed, if the player is not careful, he/she would tire out all the entities, resulting in the player wasting the allowance to use a Rage power for that turn.

Generally, the more potent Rage powers has longer cool-downs. However, the cool-down times can be reduced by upgrading the entities’ capabilities.

UPGRADING RAGE POWERS:

Like the hero, the entities in the Chest of Rage can gain experience; the narrative rationalization for this is that the entities gradually regain their strength and learn how to work around the restraints of the Chest of Rage.

Whenever the player makes use of a Rage power which is associated with any of the four entities, that particular entity gains combat experience. Eventually, an entity gains enough experience to breach a threshold, after which it gains a “level”.

When this happens, the player must make a choice between mutually exclusive and often randomized options. These options improve the powers which an entity has, such as increasing their damage output or extending their durations, but usually with the caveat of increasing their Rage costs.

Thus, the player has to consider increasing the hero’s Rage pool capacity to keep up with the costs. This can be a problem when the hero gains a level, because the player has to make mutually exclusive choices for the hero’s development too.

To cut this feature some slack, there are some upgrade options which actually reduce rage costs or cool-down times; these are more worthwhile than actually upgrading the potency of the rage powers.

LOST NARRATIVE OPPORTUNITY:

The entities in the Chest of Rage have their own backstories, but their backstories do not seem to be used for anything more than just the rationalization of their powers, how they got themselves into the artifact in the first place and lore about other worlds.

EXPLORATION:

The first King’s Bounty game was criticized for being a bit too short; The Legend will have no such complaints from players.

This is made possible through the fantastical premise, which draws from many sources of inspiration such as fantasy sagas which involve multiple dimensions, as well as even more far-fetched ones like Discworld. (There is a reference to Terry Pratchett’s works – one that becomes more apparent in later King’s Bounty titles.)

Exploring the many places in The Legend is made easy by the fact that the game simplifies traveling; the hero and his army is depicted as a man on horseback which can seemingly travel anywhere without constraints of space and sustenance. Even with thousands of units under his command, he can enter indoor spaces like cave systems and castles and fight in them without any physical setbacks.

Speaking of battles, the battlefields which the player will fight in are affected by the location where the hero is engaged in battle by hostile mobs.

The terrain type is more than just cosmetic. As mentioned earlier, some units have favoured terrain types. Terrain types also determine the kinds of neutral structures which appear on the battlefield.

Returning to the matter of exploration, most of what the player would be doing is picking up loose items like piles of gold, treasure chests and runes, as well as visiting locations such as fountains of mana and altars (which raise the hero’s statistics).

Other than that, the player would be going about visiting castles, villages and such other establishments, usually to perform quests and to recruit reinforcements.

However, going around is made challenging by the presence of often hostile mobs. These are usually groups of natives and angry wildlife, with the occasional hero posing particularly serious obstacles.

If there is any issue with exploration, it is that the hit-boxes for obstacles such as rocks and trees are not entirely clear. The hero’s model may well get caught on these objects if the player does not resort to wide turns around them.

(Unfortunately, wide turns are made difficult to pull off due to the auto-rotating camera, which cannot be disabled or controlled directly.)

MOBS:

The game makes use of another term for the wandering groups of hostile units, but “mobs” seem to be a better phrase to describe them with, considering that they have very few other goals beyond prowling around looking for trouble.

Their numbers and compositions are the challenge which they pose, but they are otherwise easily despatched by skilful players who can identify and exploit their weaknesses or nullify their strengths.

However, the player cannot initially see the composition of hostile mobs. The only clue which a fledgling hero has is the unit model which the mob uses; this represents the majority of the strength of this mob. To actually examine a mob, the player has to invest runes into the Scouting skill.

Consequently, this skill is practically a must-havef for any hero build. The developers could have realized this and made this skill redundant by having scouting available by default.

Furthermore, the game does not mention to the player that the unit model which the mob has actually does affect its movement speed. Some unit models, such as undead, move rather slowly and can be easily outrun. However, others, such as beholder and dragon mobs, are difficult to outrun. The aggro range of mobs also vary according to their unit models.

Nevertheless, an observant player would notice that he/she can use the map to outwit the mobs with. There are many maps with roundabouts, which can be used to confuse mobs – that is, assuming that the player does not run into hit-box problems, which have been mentioned earlier.

ENEMY HEROES:

Some mobs are more special than the rest. These have special illumination effects, namely spires of light. These mobs also make use of altered variants of unit models.

These mobs are much harder to deal with, mainly because they are led by heroes which have capabilities which are similar to those of the player’s own hero, chief of which is their ability to cast spells and grant their statistical bonuses unto their own units.

The other capabilities which enemy heroes have are not clear, however. Although the player can see their statistics, other information such as their spellbooks and their gear is not readily available, even during battle. This can lead to some unpleasant surprises, one of the worst being that the opposing hero can somehow increase the initiative of his/her units.

There are a few gear pieces which can increase the initiative of units, so ostensibly such enemy heroes have them. However, the player is not shown their inventory.

Ultimately, heroes are mainly only in the game as sources of greater challenge and some lore. Most of them rarely matter to the story in The Legend.

UNEVEN STRENGTH OF MOBS:

There may be an issue about how Katauri Interactive has designed the strength of the mobs which populate the lands which the hero will have to go through.

In the first few lands, the mobs in them are a lot more manageable. The powerful ones are slow-moving or are static, whereas the ones which are within the hero’s league can be defeated in order to build him up.

Later in the game though, the mobs become a lot more powerful with patrol paths which are more difficult to circumvent. More accommodating players would take this is as a sign that they should go elsewhere to build their strength and skilful players would take this as a challenge, but others would see steep obstacles to what should have been more opportunities to explore the lands seen in The Legend.

DIGGING:

The hero happens to be one of few individuals who are gifted with the ability to somehow perceive the presence of buried treasure. In fact, the Kingdom of Darion – which the hero serves – has a royally appointed position for such individuals. (Of course, the hero starts with this position outright.)

Whenever the hero approaches a place where there is buried treasure, a beacon of light emits from the ground; this is accompanied by a chime. There is a slight delay for these indicators though, so if the player wants to be thorough, he/she has to have the hero linger about a patch of ground for a couple of seconds.

After locating a treasure, the player only needs to click on the “dig” button to have the treasure appear. Digging is a simple affair, with no noticeable consequences for not digging up anything (much unlike digging in the Heroes of Might & Magic series).

However, not all treasure locations are immediately apparent to the player. For whatever reason, there are quests which involve treasures that are only visible after the player has progressed in the quests.

The scripts of treasure-finding quests go against the narrative of the hero’s special ability to find treasures without even knowing that they are there.

TIME OF DAY:

There is a cycle of night and day in the game, which grants different lighting unto the lands which the hero would travel through. However, the differences between night and day are not entirely cosmetic. There are some gameplay elements which are tied into this feature, such as the Night-time Operations skill and the ability of some units to fight better during the night.

These are not significant enough as to be crucial to battles though. Besides, some locales, such as the underground, are not affected by day/night cycles.

SAILING:

In addition to moving around on horseback, the hero can embark on a ship to move around bodies of water.

The ships which the player uses are only ever usable in the map which they appear in. Embarking and disembarking do not appear to have any consequences. Furthermore, battles at sea do not appear to have any significant differences beyond the presence of a few unit types which perform marginally better in battles on ships.

Thus, ships do not seem to be any more than horseback-travel with a maritime cosmetic re-skin.

However, to give The Legend some credit, there do appear to be far less hostile mobs at sea and hostile mobs on land cannot pursue the hero into the water. This lets the player find a way around the patrol paths of powerful mobs.

QUESTS:

Staying true to its roots, The Legend is mainly about having adventures – seemingly one after another with no overarching plot to tie them all together, at least not until late into the story.

In hindsight, The Legend’s story may have been little more than an excuse to introduce Katauri’s vision of the world of King’s Bounty. This is not necessarily a bad thing of course.

Considering the adventures – and trouble – which the hero would be getting into, it is fortunate that there is a quest log-book. The log-book gives brief descriptions of the quests which the hero is undertaking, as well as what needs to be done to progress in them.

Interestingly, the rewards of the quests are stated too. This helps the player pick which quests to pursue first, if only to get an edge when pursuing other quests.

Most of the quests which the player would pursue are fetch quests or search-and-destroy missions. If the player is not doing this, then he/she is usually tracking down someone or something to talk to him/her/it, and after that, return to the quest-giver. More often than not, these quests would require the player to fight some battles, especially those quests which are categorized as “primary”.

The quests which are not the usual ones do not necessarily provide entertaining variety either. A few are practically escort missions, which can be annoying to deal with because of the escorted person’s bad path-finding.

Some others are a bit more amusing, such as one which involves the solving of puzzles. However, the appeal of such quests are often held back by the small text and icons which are so pervasive in the game (more on these later).

A few quests are apparently off-limits to the player until the hero has achieved certain levels in his statistics. Examples of these include the challenges offered by the magical institutes of Darion.

Some quests, including the primary ones, appear to give the player a semblance of choice. However, the quests which actually do these have short-term consequences with nothing significant further down the metaphorical road. The ones which appear to have long-term consequences ultimately disappoints because they shoe-horn the player into a fixed story progression anyway.

In most other games with quest systems, the player is usually better off pursuing side quests so as to gain more resources and power before progressing in the main story. In King’s Bounty: The Legend, the player is actually better off pursuing the main quests as soon as possible.

This is because one of their rewards for completing them is the bestowing of noble titles onto the hero. Far from being mere titles, these increase the hero’s leadership rating by tremendous amounts. Of course, having a bigger army is always a good benefit. Furthermore, the side quests tend to throw more difficult battles at the player.

There are some side quests with time limits; these are suggested by the descriptions of the quests, but otherwise the player does not appear to have any timers for these quests. (Considering that the game does show information such as the rewards for these quests, this is an odd omission.)

The player can also fail at some side quests, if the player does not follow their instructions carefully.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

For a game of its time, King’s Bounty: The Legend is quite the looker. (Discounting the bland-looking splash intro for 1C Company), the game makes a good first impression through the artwork which adorns the main menu.

Although the game starts the player out in some dingy dungeon which is used to test would-be graduates of Darion’s School of Knights, the amount of detail and animations in the environs in this starting map alone would have been impressive during the time of this game.

The animations and other graphical designs for the battles also make a splendid first impression. Each unit type has its own set of associated animations, such as the deft sword-swinging which the Swordsman makes when he is idle. Unit models also have celebratory animations for when they defeat an opposing unit stack. There is not a lot of variety to be had among them, however.

As mentioned earlier, the player will be moving through many kinds of regions. These are distinctively different from each other. For example, the Kingdom of Darion has a mixture of terrain types, such as the farming-friendly lands around its capital Kronberg and its creepy and startlingly immense cemetery district.

As another example, the elven lands of Ellinia are vibrant life-filled forests, but tainted here and there by the presence of the dreaded Books of the Dead.

However, over time, some of the game’s visual designs, especially those for unit and spell animations, might eventually seem repetitive.

There are also some odd animations, the most apparent example of these being the terrain-hugging model of the hero. The sight of the horse and its always-perpendicular statue-like rider hugging the terrain at any angle can be amusingly strange.

SOUND DESIGNS:

Like the game’s visual designs, its sound designs start out splendidly but eventually become repetitive, given the length of the game.

(After the aurally jarring 1C Company splash intro,) the game starts itself off with the hauntingly melodic track for the main menu. The other tracks have similar instruments too, though they are not as memorable (if only because they are not the main menu track).

There are several soundtracks, most of which are thematically matched to the themes of the lands seen in the game. However, the player would eventually notice repetition. For example, although it has one track with actual lyrics, the forests of Ellinia share most of its soundtracks with the kingdom of Darion’s.

PLETHORA OF MINOR ISSUES:

There is apparently no shortage of fans who like the original King’s Bounty; Katauri Interactive is one such fan and its devotion shows. Unfortunately, Katauri – and 1C Company - is not going to alleviate the impression that games which are developed in former Soviet territories have many issues.

NO MAPS FOR INDOORS AREAS:

The game makes use of 2D top-down views of the otherwise 3D-modelled levels to create maps with. This makes it easy to know which locations on maps refer to which locales in the lands of King’s Bounty.

Unfortunately, there do not seem to be any maps for indoor areas.

SMALL TEXT AND ICONS:

The screenshots which have been shown thus far in this review should already hint at an issue of user friendliness within the game. They are taken and cropped at 1:1 ratios, so the text in them, if any, is not altered in size. Apparently, the text is rather small.

Fortunately, the game does not inundate the player with text too many times throughout the game, so reading the small text should not be too much of an issue.

TRANSLATION ISSUES:

(This review is done with the English version of the game.)

The most significant problem with the game lies in its translation. These translation issues detract from the brevity of serious situations, such as plot twists, and also reduce the impact of otherwise humorous statements.

Then there are those which affect gameplay, which have been described earlier in this review.

BUGS:

At this time of writing, the current build of the game (version 1.7) is quite stable and there are not too many game-breaking bugs. However, some issues still linger from the launch version of the game.

Chief of these is the unpredictable hitbox of the hero’s model, which causes it to get caught in pieces of terrain such as sign-posts, trees and rocks when the hero is moving around the lands of King’s Bounty. This issue will be of particular annoyance to players who prefer to lure mobs around or avoid them.

Another serious bug is how players can lose unit stacks which have been placed in garrison slots if he/she attempts to move these into his/her already full army. There is no warning from the game that the player lacks empty slots in his/her army when trying to do this; the unit stack which was formerly in a garrison slot is simply lost.

CONCLUSION:

Despite its translation issues, lack of thorough documentation and lingering bugs, King’s Bounty: The Legend is far from a poorly conceived game. Of course, there can be the criticism that Katauri Interactive has never realized and fixed these issues during the years since the release of The Legend and it has instead focused on churning out expansion after expansion. However, King’s Bounty: The Legend fulfills a niche for single-player versions of Heroes of Might & Magic.