Game Addiction: The Real Story

What is video game addiction? What are its boundaries, its symptoms, and its treatments? How wide is its scope? In this GameSpot AU feature we speak to researchers, psychologists, medical bodies, and gamers to gauge their thoughts on the cause and effects of video game addiction.

What is video game addiction? What are its boundaries, its symptoms, its treatments? How wide is its scope? And is it even a medically recognised condition in the first place? In Part One of this GameSpot AU feature we speak to researchers, psychologists, medical bodies, and gamers to gauge their thoughts on the causes and effects of video game addiction, the significance of its recognition as such, and the potential for future research. We also look at this issue from the game makers' side, as well as explore some real-life cases of addiction.

If asked to define "video game addict," most of us would reply that a video game addict is someone who likes to play a lot of video games. But that definition is as close to the truth as the definition "someone who likes to inject a lot of heroin" is an accurate portrayal of a heroin addict. Our unfamiliarity with video game addiction stems not just from the ease with which the term "addiction" is thrown around, but also from a vast misrepresentation of the issue in the mainstream press, with sensationalist headlines like Video game addicts are not just shy nerds (June 5, 2008, Chloe Lake, NEWS.com.au) not an uncommon sight. Add to this a lack of medical and psychological research, and it's no wonder we think video game addicts are just people who like games too much.

Defining game addiction

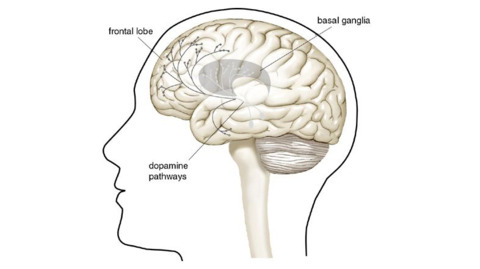

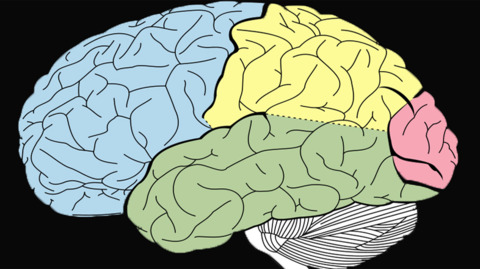

Before we explore whether video game addiction exists and what form it takes, we need to know what it means to be an addict. At its core, addiction is a psychological disorder that affects the way the brain functions by impacting chemical processes related to motivation, decision making, learning, inhibitory control, and pleasure seeking. Behavioural addictions like gambling and sex are forms of psychological dependence; addictions to substances like drugs and alcohol are forms of both psychological and physical dependence.

An addict is defined by his or her psychological compulsion to carry out certain behaviours or consume certain substances that are often detrimental to his or her health or well-being. Although this repeated consumption often leads to other problems in areas of social and mental health, an addict cannot stop him- or herself from recurrent use. The hallmarks of addiction are often an increase in time spent in the consumption of these behaviours or substances at the expense of other activities; recurrent failed attempts to stop; and recurrent preoccupation and intense psychological urges or desires that are difficult to control.

Video game addiction is still a newcomer to the field of psychology and is not yet medically recognised as a proper addiction due to the lack of research conducted into its causes and effects. So, while it's common for clinics to specialise in the treatment of drug, alcohol, gambling, sex, and other addictions, it is not common for clinics to specialise in the treatment of video game addiction. However, during the last five years, countries like China, South Korea, the Netherlands, Canada, and the USA have begun to recognise the health threat posed by video game addiction and have opened clinics that deal specifically with the problem.

The argument for excessive video game play as a real psychological addiction is that a person gains psychological reinforcement from playing, and excelling at, a game. By becoming an expert at a game, a person releases a neurochemical known as dopamine in his or her brain, whose function is to make us feel good. This is a natural response humans have to good experiences, such as eating favourite foods, listening to music, or watching a good movie. For it to be a psychological addiction to video games, it rests on how much dopamine is released in those who are believed to be video game addicts, in comparison to the levels released during other positive lifestyle activities.

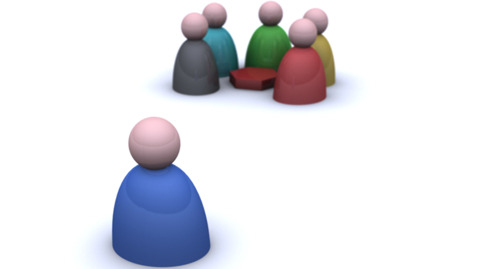

Symptoms of video game addicts are varied--they can range from social isolation, poor social skills, and erratic mood swings to neglect of responsibilities such as health, regular sleeping, hygiene, financial commitments, and work and study responsibilities.

A new addiction

Now that we know what addiction is, we need to see if video game addiction fits the pattern of a medically recognised addiction. In July 2006, the world's first video game addiction clinic opened in Amsterdam. The event sparked the curiosity of the global press--it was the first time video game addiction was acknowledged, and the subsequent coverage pointed to the increasing popularity of video games and the people who just couldn’t stop playing them. Almost all media reports at the time and subsequent reports dealing with video game addiction pointed to the few instances of video-game-related deaths as examples of addiction, wishing to demonstrate the debilitating effect of video games. But few reports actually defined addiction or indicated that not all video game addicts eventually kill themselves, or others, through excessive playing.

The cases most often cited include a South Korean man who collapsed in an Internet cafe after playing Starcraft for 50 hours; a man in China who died after playing online games for 15 days consecutively; a 13-year-old boy from Vietnam who strangled an elderly lady with a piece of rope because he wanted money to buy games; and a number of cases in the United States involving angry teenagers murdering family members over games and consoles. The fact that the latter cases have more to do with displays of deep mental instabilities rather than addiction was not mentioned in the reports, an omission that no doubt has contributed to the public's widespread confusion about what video game addiction really is.

In the research field, things are a little different. The last five years have seen a progress in the recognition of video game addiction as a real addiction, with more research dedicated to studying its scope, causes, and effects. At the 2006 annual meeting for the American Medical Association (AMA), a resolution was adopted commissioning the AMA's Council on Science and Public Health (CSAPH) to prepare a report reviewing and summarising the research data on the emotional and behavioural effects of video games, including addiction potential. The report, based on information from scientific literature from 1985 to 2007, concluded that there is currently insufficient research to definitely label video game overuse as an addiction. However, the report's authors used several case studies and surveys to find evidence of video game addiction, arguing that symptoms of time usage and social dysfunction/disruption present in video game overuse also appear in other addictive disorders, and, despite its reluctance to name video game addiction as a definitive mental disorder, the CSAPH recommended that the AMA strongly encourage the inclusion of video game addiction as a formal diagnostic disorder in the upcoming revision of the American Psychiatric Association's (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

The DSM is widely recognised as the standards manual defining mental disorders. It provides diagnostic criteria for mental disorders and is used by researchers, doctors, health insurance companies, and pharmaceutical companies and policy makers. It has been revised five times since it was first published in 1952, updating existing disorders and adding and removing new and redundant disorders. The CSAPH's recommendation to encourage the inclusion of video game addiction in the upcoming DSM was followed up by the AMA in June 2007, and, in response, the APA stated that "if the science warrants it, this proposed disorder will be considered for inclusion in the DSM-V, which is due to be published in 2012."

GameSpot AU contacted the APA and received the following statement in regards to video game addiction and the 2012 edition of the DSM: "There is no way to state specifically whether or not the issue of video game addiction will or will not be included [in the DSM of 2012]. What we can say is that our workgroups are considering all issues, new science and research as they are continuing work on the DSM-V."

A need for research

Studies into video game addiction are scarce. However, the increased recognition of the issue amongst the scientific community means more and more researchers are beginning to look seriously at video game addiction. Daniel Loton, an ethics officer and former psychology honours student from Victoria University, used his thesis to explore the relationship between social capacity and problematic video gameplay to try to determine the cause of video game addiction. Loton used the Social Skills Inventory (SSI), a broad scale that measures basic social skills, to survey 560 male and 61 female gamers with an average age of 23.4 years. His survey found a very small connection between social capacity (that is, social skills and self-esteem) and video game playing. Given the past research on the topic, Loton said his study yielded surprising results.

"To use the words of the American Medical Association after it had conducted a review of the literature, problem gamers are likely to be...somewhat marginalised socially, perhaps experiencing high levels of emotional loneliness and/or difficulty with real-life social interactions," Loton said. "Considering this past research, I would have expected social skills and self-esteem to drop as problematic play increased. Instead, only a tiny relationship emerged."

The results revealed that basic social capacity is not the central cause of problematic video gameplay. Broadly speaking, no serious negative consequences of playing video games were revealed, even when playing to the extreme. Loton thinks his results may turn attention away from the assumed link between social capacity and problematic video gameplay and direct attention to other characteristics such as behaviour moderation, depression and stress, locus of control (that is, feelings of control one has over one's environment), and arousal (using games to get excited or to relax).

Richard M. Ryan, a psychologist and professor of psychology, psychiatry, and education at the University of Rochester in New York, has been focusing on a different aspect of video game addiction: motivation. Ryan and his team are testing the idea that psychological needs for control, mastery, and connection can be readily satisfied within games.

"People can feel a lot of autonomy and competence during play, and also it can be a place to relate with others, albeit in a virtual context," Ryan said. "We think that this poor self-control, combined with a more impoverished life, leads a subset of players to sink deeply into the gameworld and in time to feel an obsessive need to play. The obsessive player feels he/she has to play, does it too much, and gets less fun and satisfaction out of it. It also crowds out other satisfactions in life, compounding the problem."

Ryan and his team found that when games were played for less than 10 hours a week, there was no evidence of negative effects on wellness; when games were played in excess of 20 hours a week, signs of ill-being emerged--negative mood, symptoms of depression, and more impoverished relationships. The team's studies showed that those who overuse games are getting fewer of their needs satisfied in their lives outside of games.

"We also discovered players who report obsessive attitudes toward games--they are preoccupied with their games, feel compelled to play, and feel tension when they cannot or are not playing. This latter set of players also shows signs of negative effects on psychological functioning."

Ryan thinks the lack of quality research into video game overuse will be rectified with time as games become more sophisticated in the ways they satisfy people’s psychological needs.

“We have a lot of people, some in the media and some in the sciences, who are too ready to make very strong claims about video games, whether we are talking about aggression, addiction, or cultural estrangement, based on very little evidence. I think that is especially how the media often sells stories. Some commentators exaggerate risks, and on the other hand there are defenders of games who deny any and all problems and attack any perceived bad news.

"Games are relatively new in our culture, and such vacillation between hysteria and denial I suspect often greets any new phenomenon, from hip-hop to the Internet to video games. Both sides usually have some part of the truth, but it may be a while before at least we as scientists, much less as a society, have a coherent understanding."

Check back with GameSpot next week for Part Two of our game addiction feature. We'll look at more studies into the issue and what game publishers are saying, and we'll talk to some gamers who consider themseves "addicts." In the meantime, hit the comments below and tell us if you think video games can be a real addiction, whether you know people who have a problem, and more.

Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

In Part 1 of Game Addiction: The Real Story, GameSpot AU defined addiction and explored the nature, symptoms, and scope of video game addiction and its potential to be widely recognised as a clinical addiction. In Part 2, we look MMORPGs, talk to Blizzard about World of Warcraft, and speak to a few self-confessed video game addicts to get their perspective.

Achieving a coherent understanding of video game addiction may be easier said than done. Putting aside the lack of research into the subject, there is always the immediate human reaction to find blame for a phenomenon that’s not yet understood. Whenever the subject of video game addiction arises in the public forum, there is one type of game that is almost always mentioned: massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). Based on what we already know about addiction, it is clear that addictive behaviour can occur when playing any type of game. However, research to date has focused more on MMORPGs due to their highly competitive and in-world social nature.

MMORPGs

Dr Andrew Campbell runs the Brain and Mind Research Institute Clinical Centre at the University of Sydney, a child and adolescent practice that has dealt with video game addiction involving MMORPGs. Dr Campbell and his team have looked closely at the factors that attract players to games where they are willing to give up other aspects of their life in order to play.

“The types of games these players were obsessed with were very popular titles that involved complex economies and merit systems,” Dr Campbell said. “They gave each player a sense of being skilful, clever, and part of a team or community. They also instilled in them a sense to continue with the game no matter how many rewards or ‘levels’ they attained in the game. More often than not, the players never thought about the end of a game, especially in a MMORPG world.

“We have looked at how some players gain self-esteem from the ‘mastery’ of a game--thus leading us to the hypothesis that these types of players are always looking for a place in a social group where they feel valued, admired and ultimately, comfortable. In the case of video games, players do not feel as much of a ‘body’ response to winning, but more of a mental sense of satisfaction that impacts their ego and sense of self. They want to continue feeling this, and so return to the source--the game itself.”

According to Dr Campbell, research into video game addiction conducted from the early 1980s to the present has been contradictory on the seriousness of it. While some theorists believe that video game playing is an example of obsessive rather than addictive behaviour, other theorists believe video game addiction could be as serious as gambling, alcoholism and even drug addiction.

His own research to date has been inconclusive, but has led Dr Campbell to raise new questions about what factors obsessive video game players attain from playing games, in comparison to what they would desire to have in their social lives if they had to give up playing video games.

“For example, do they want popularity, do they want to engage often in competitions where they can demonstrate mastery or do they simply want to achieve a feeling of belonging to a community?”

Dr Campbell says that whether video game addiction exists, or whether it is merely obsessive behaviour that is detrimental to the social and healthy development of gamers, the best treatment is prevention.

“Gamers who think they may be addicted need to take the time to see how their lives have changed since playing a game continuously. What friends do they associate with and what are those friends interested in? Are they more moody, losing sleep and generally disinterested in any activities outside of the games they play? If a person is concerned that they may have a problem with their video game playing behaviour, the most important thing to do is talk their concern over with a close relative or trusted friend who is not involved in the same gaming behaviour as the person.”

The 2007 report into the addictive nature of video games published by the AMA’s Council on Science and Public Health also pointed to MMORPGs as a particular concern, indicating that although video game overuse can be associated with any type of game, it is most commonly seen among MMORPG players. According to the report, MMORPG players represent approximately nine per cent of gamers. The report stated that:

“Researchers have attempted to examine the type of individual most likely to be susceptible to such games, and current data suggest these individuals are somewhat marginalised socially, perhaps experiencing high levels of emotional loneliness and/or difficulty with real life social interactions. Current theory is that these individuals achieve more control of their social relationships and more success in social relationships in the virtual reality realm than in real relationships.”

It’s no secret that the most prevalent MMORPG is World of Warcraft. With a subscriber base currently sitting at 11.5 million subscribers, the game is a phenomenon. World of Warcraft’s second expansion pack, Wrath of the Lich King, sold 2.8 million copies in the first 24 hours of its release in November last year, going on to sell over four million copies in the first month. Given the game’s scope, its players more than likely make up the majority of the nine per cent of those who play MMORPGs. And as such, it's no wonder that WoW often finds itself portrayed as the addict's choice when it comes to mainstream coverage of game addiction. Blizzard has previously acknowledged its game's addictive potential, and says it has built in specific features within the game to try and curb the problem.

"Like most other games, World of Warcraft is designed to be fun and compelling and should be recognised as another means of enjoyment, such as watching television, playing sports or reading books," a Blizzard spokesperson told GameSpot AU. "As with those forms of entertainment, it is ultimately up to the individual player or his or her parent or guardian to determine how long he or she should spend playing games. We feel that a person's day-to-day life should take precedence over any form of entertainment, and in fact, World of Warcraft has elements that allow players to take natural breaks.

"For example, as World of Warcraft players advance their characters in the game, they can benefit from a feature called the Rest System, an integral game mechanic designed to enhance gameplay, which rewards them with an experience boost based on the amount of time spent between play sessions. This feature has been in the game since launch. Players can also use the in-game clock to set an alarm that notifies them when their desired playtime has been reached. Another example would be the design of the quests and dungeons in World of Warcraft. Quests can generally be completed by individual players or together with friends in less than an hour. The same goes for many of the game’s dungeons, which are designed to be completed wing by wing at the player’s discretion rather than all at once. This design allows players to make appreciable progress in the game with a minimal time commitment during any given play session.

"And for minors, the game’s parental-control system makes it easy for parents and guardians to set play schedules for the account. This feature is very straightforward, and it’s web-based, which means parents and guardians can manage their child’s access to the game from any browser, as opposed to having to log in to the game to do so. To use it, parents or guardians simply select blocks of time, such as homework time after school, when the game will be inaccessible for that account. We’ve even provided pre-made schedules, such as 'weekends only' and 'after school and weekends', to make things easier.

Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

A different perspective

Between clinical research, public perspective, and the gaming community’s understanding of video game addiction, there is another point of view that demands a voice: the self-confessed addict’s.

David, a 28-year-old gamer from Mt Isa in Queensland, Australia, spends up to 20 or more hours a week playing games, usually first-person shooters. Although he’s been a gamer for 15 years, it wasn’t until his recent decision to start studying again that he first noticed his habit was becoming a problem.

“My sleep, studying and physical condition have all suffered because I play games too much,” he said. “Sometimes it takes me a while to fall asleep because I think about a game I’m playing. I also leave assignments to the last minute. I find it especially frustrating if I am left alone for a day, because I will end up playing way too much.” David says that he does not suffer if he has not played for a period of time, but he admits he always has a game at the back of his mind, acknowledging that if he continues his habit he will also continue to suffer in other aspects of his life.

Twenty-three-year-old X (who does not wish to be named) also plays more than 20 hours of games a week. He’s been playing games since the age of six, beginning by favouring RTS games and eventually moving on to shooters and strategy games like Call of Duty 4 and Warcraft 3, and RPGs like KOTOR and Oblivion. He says gaming became a problem when he was first left alone to monitor how much time he spent playing them.

“I was 14 and there was nothing really stopping me from playing too much, so I did. Over time, I’ve found that the more I game, the harder it is to concentrate. For example, I find it extremely hard to just sit down and write an assignment or do some reading for university; every few minutes, my mind is wandering back to games. If I haven’t been playing games for a week or two for one reason or another, then I find my concentration improving and gaming doesn’t dominate my thoughts nearly as much.”

X says that to some extent, most aspects of his life suffer due to excessive gaming: study, social life, relationships and health.

“I know that if I spent even one fifth of the time that I game on study, then my grades would have been a lot better. On more than one occasion I’ve stayed in and gamed instead of going out. And as far as wellbeing goes, I have trouble sleeping, my posture isn’t great and I even carry my right shoulder forward a little because I use it for the mouse, which has given me shoulder problems. I even get in a bad mood when I perform badly whilst playing," he said.

“During the period of time I’m playing games and in the short term (a few hours, to a couple of weeks) after quitting them, I can experience anything from insomnia, to trouble concentrating, to restlessness--usually all three. It’s after I haven’t played any games for a few weeks that these symptoms start to disappear.”

In X’s group that he plays games with, gaming is encouraged--the group has developed its own subculture around playing, and there is never talk of ‘excessive gaming’. However, X has found relationships with other groups of peers and his parents have suffered. When it comes to defining what his habits mean, X believes the problem is psychological.

“I find that when I’m playing games, I’m fine and most other times when I’m not playing games, I want to be playing games. I don’t know what will happen if I continue to play games this way--I have full-time employment lined up for next year which is probably going to dominate most of my waking hours, so it might be that a lot of my problems take care of themselves. Then again, if I only have a few hours to myself every night and I’m filling them with gaming, then my social life might suffer even more.”

X says he has never thought about getting outside help, but would consider it if more aspects of his life begin to suffer. In the meantime, he sees video game addiction becoming an increasing problem in society as more people become gamers and the competition aspect is played up.

“Where you have a problem that isn’t recognised as a problem and where the effects aren’t readily identifiable or measureable, then that problem is going to get a lot worse before enough people realise it’s there and resolve to do something about it. Couple that with the fact that gaming is also coming more and more into the mainstream and you’ve got a bunch of serious problems sitting just off the horizon. For the first time, a large percentage of the population is gaming and in the next few generations, I can only see that figure increasing.

“There’s also the status of gaming itself. Clans are being sponsored, the industry is booming and players are actually making money out of it. People are making a living from playing games. Gaming is being marketed like a sport, which in many ways is a fair classification--it’s often highly competitive, takes skill and teamwork. However, there are some serious negatives to playing too many games, negatives which don’t exist with normal sports.”

What are your thoughts on game addiction? Is it real? Is the issue being over-inflated? Tell us your comments below!

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation