The History of Football Games

This special feature examines the history of simulated football on video game systems ranging from the Atari 2600 on up to the modern era.

Design by James Cheung

The History of Football Games

The Early Years

Part of this was due to the way that the National Football League surged in popularity at the same time as the video game era dawned. Thanks to the efforts of commissioner Pete Rozelle and innovations like ABC TV executive Roone Arledge's Monday Night Football, the NFL was enjoying an unprecedented explosion in public support. So when the Atari 2600/Video Computer System (VCS) and Mattel's Intellivision brought video games to our living rooms in 1977 and 1979, respectively, there was really only one sport that people wanted to play on them. The idea that those little black boxes would be able to drag Sunday afternoon and Monday evening through the rest of the week was a huge selling point for the console systems.

Of course, reality didn't quite match expectations. Gameplay was generally very crude, even by the lowered standards of the time. In 1978, Atari's Football for the 2600 employed three-man teams consisting of players who looked like washing machines and a field that filled a single screen. You could call plays on both sides of the ball, but only basic ones that shifted receivers and backs from one side of the field to the other. Intellivision's NFL Football arrived a little more than a year later with more sophistication, boasting five-man squads with players who had moving arms and legs and the ability to use elaborate formations. There were serious drawbacks, however, most notably molasses-slow animation and the complete absence of artificial intelligence that made two players a necessity.

When the Commodore 64 became fashionable as a gaming machine in 1984, football game development kicked into high gear. These early computer football efforts were generally more complex than their console cousins, even simplistic fare like Gamestar's On-Field Football. Some could still be categorized as rather advanced simulations. 4th and Inches from Accolade was published in 1987, yet it remains playable today as an arcade experience with a little bit of depth. Design evolutions, along with advancements in technology and programming skill (a lot more could be jammed into an Atari 2600 cartridge in 1984 than in 1980), were increasingly seen through the end of the decade on both consoles and computer systems. Tecmo released Tecmo Bowl for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in 1988, kicking off a sensation that lingers to this day. The smart, fun gameplay spawned a sequel, Tecmo Super Bowl, that is now 10 years old but is still being played in online leagues. A pinnacle was reached in 1989 with Cinemaware's TV Sports Football. It was jammed with more features than any of its predecessors. Full season play, coaching mode, and playbooks that varied from team to team made it the template for everyone else to copy.

Good or bad, football games were popular in the 1970s and 1980s. Even though they were simplistic in comparison with the real thing, football titles asked more of the gamer than those depicting the other big three North American sports. Being required to outwit your opponent as well as outplay him provided football gaming with an added strategic element that couldn't be matched by baseball, basketball, or hockey. Playcalling may have been rudimentary, but it was still there, and it gave players an extra dimension that was more interesting than the simplistic arcade challenge of hitting a ball, sinking a basket, or scoring a goal. It may be strange to think of a small playbook and stick-figure players as being representative of any great depth, but they seemed almost unbelievably refined in comparison with their rivals.

Over the following pages, we look back at those early days, tracing the evolution of football as console video game and computer simulation. This piece concentrates on the major football titles of the past, although reference can be found to lesser-known works. For example, all of the football games produced for the Atari 2600 can be found under the main heading of Atari's original Football. Regardless of status, most of the games themselves are now no more than nostalgia pieces. Some can still be entertaining diversions--something that was proven during the extensive research that went into this article--and all serve to show how far we have come since 1978. Those too young to have experienced these games firsthand would do well to read on before they complain too much about comparatively minor problems with today's games.

Football

Atari

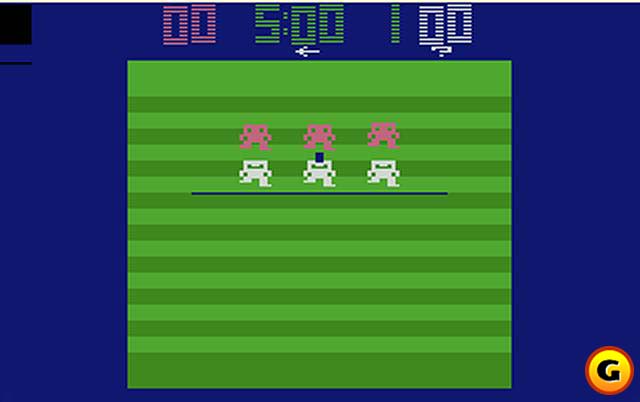

Football gaming didn't get off to an auspicious start. Atari's Football for the 2600/VCS arrived in 1978, in the vanguard of titles released for the console system in the first year after its launch. High expectations for the game on the part of both its publishers and eager consumers were dashed in short order, however, as Atari delivered a rather atrocious effort that didn't resemble any sport ever played by human beings.

Atari's take on football rejected most of the rules and conventions of Vince Lombardi's game in favor of an almost surrealistic experience. Teams consisted of three-man squads composed of players who more closely resembled appliances than people. They moved their way up and down a tiny vertical field without yardage markers, end zones, or goalposts. Aside from the four-down system, safeties, and the ability to punt, nothing of real football survived. There were no field goals or point-after-touchdown conversions. There were no interceptions, no fumbles, and no going out of bounds. Tackles were automatic on touching the ball carrier, the ball could be guided in flight on passing plays, playcalling involved little more than slightly varied formations, and the lack of computer AI made two players a requirement.

Poor visuals affected play as well. Programming for the Atari 2600 was in its infancy, and little was known about how to push the system to its limits. As a result, even the rough graphics on display here suffered from problems with flickering players and ghost tackles. Stuttering animations turned plays into strange crawls through which everything seemed to be happening in slow motion.

Still, the idea of "programming" players to run specific pass routes on offense or cover certain areas of the field on the other side of the ball was intriguing. And even somewhat advanced for the time, considering that the only real competition were handheld LED-based games like Coleco's popular Electronic Quarterback. Also interesting were two game options that let you call plays as a coach and then watch the computer carry them out on the field. Another good idea was Atari's placement of a line on the field, which showed where you needed to move the ball to collect that all-important first down. Other game designers took the better part of a decade to pick up on that innovation.

Disappointment in Football and competition from Intellivision's strong line of sports games in 1979 and 1980 pushed Atari and other developers to design better football games for the 2600 in subsequent years. These later efforts made the initial one look like something produced in an era of stone knives and bearskins. Intellivision producer Mattel ported its NFL Football game (see below for more) to the rival system in 1982 with good results. The M-Network-labeled Super Challenge Football featured five-man teams with players that had actual moving arms and legs, along with a regulation 100-yard field complete with scrolling and yard markers. Playcalling was far more interesting, as you could individually program each lineman with specific blocking instructions. Interceptions were also possible. But that was about it in terms of sophistication--you couldn't play against the computer, you couldn't punt or kick field goals, and there was no going out of bounds. Even more strangely, you could run off one end of the field and reappear at the other. Players could have linebackers run in the opposite direction and emerge directly behind the opposing quarterback--and were actually advised to do so in the tips section of the game manual!

Atari responded to the Intellivision threat with the RealSports line in 1982. This series included most of the major sports, including baseball and soccer, though football was perhaps the most successful entry in the lineup. Overall gameplay wasn't as good as that provided by the rivals at Mattel, though you could at least play solo against the computer here. Teams consisted of five players each, but the visuals were crude and tended to flicker. The field, while regulation-size and of the same side-scrolling type introduced by Intellivision, lacked hash marks and sidelines. Plays were slightly more advanced versions of those found in Football, though field goals were finally possible.

With the great video game crash of 1983-1984, the viable shelf life of the Atari 2600 abruptly ended. Even its intended successors, the unimaginatively monikered Atari 5200 and 7800, were critically wounded by this slump. Games continued to be designed for all three systems throughout the 1980s, though sales were poor due to the rise of more advanced alternatives such as the NES, Sega Master System, and the Commodore 64 computer. Super Football was the last of the Atari 2600 football games to emerge. Unfortunately, it didn't hit the market until 1988, when an Atari 2600 was about as commercially and culturally relevant as a Nehru jacket. Obsolete platform or not, Super Football was very good. It could even be considered a predecessor of contemporary football gaming in that it used a scrolling 3D field, colorful, more realistic graphics, and an impressive selection of plays.

Production of the Atari 2600 finally ceased in 1991, ending a lengthy history that began in 1977. More than 25 million units are estimated to have been sold during that time, firmly establishing the system as the foundation of the home video game era.

NFL Football

Intellivision (Mattel)

The popularity of home video gaming and the rise of the Atari 2600 didn't go unnoticed. Mattel began investigating the possibility of developing a rival system in 1977 and soon realized that components and design schematics were readily available. After some initial misgivings about going head-to-head with Atari and its Time-Warner parent and a brief foray into handheld gaming, the decision was made to proceed, and the Intellivision was born in 1979.

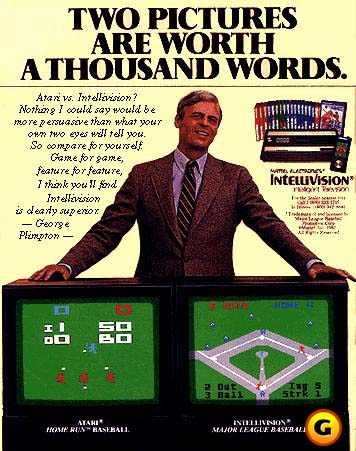

Mattel's take on a home video game system was much different than Atari's. For starters, technology was more of an issue. General Instruments provided a superior CPU, and greater effort was made to ensure that the Intellivision could display more complex visuals and emit higher-quality audio. This refinement was used as the primary selling point--the company decided to market itself to adults and set up its system as the mature alternative to kid-oriented Atari and its arcade licenses, like Space Invaders. Sports gaming was used as the primary weapon in this PR fight. Snooty author George Plimpton was recruited as a pitchman for the Sports Network series of games, which included titles based upon all of the major and not-so-major sports (from baseball to auto racing), with football being the most prominent.

Intellivision's NFL Football deserved this attention when it went into wide release in 1980, as it was far more advanced than its Atari counterpart. There was really no way to even compare the two, as Plimpton had asked, since despite the close proximity of their respective release dates, a huge gap separated them on the evolutionary ladder. The chunky players of Atari's Football were replaced with models that looked more like real people, with arms and legs that moved and animation that mattered. Tackles weren't just automatic upon a brief touch of the ball carrier; here, you had to actually line the enemy up or risk having him scamper away. The field scrolled sideways, allowing a more realistic depiction of a regulation field that clocked in at the usual 100 yards and featured end zones. There were no goalposts, though field goals could still be kicked by booting the ball over the center of the goal line. Players could go out of bounds, make interceptions, hammer the opposing ball carrier for a safety, punt on fourth down, and so on.

Playcalling was equally ambitious. The Intellivision's numeric pad controllers were designed to allow for more intricate gameplay, and NFL Football benefited greatly from this. Plastic controller overlays and playbooks covered the nine offensive and nine defensive formations available in the game. Each was designed to stage or prevent specific plays and was very effective. Pull one over on the defense, and you could spring a long gainer. Pull a surprise on the offense, and you could be welcoming your opponent to sack city. About the only limitation was the lack of solo play against the computer.

Perhaps the most astounding thing about NFL Football was its longevity. It was so far ahead of its time that it served as a worthwhile diversion for football fans through the end of the decade. Even though Intellivision remained in limited production until 1990, it was never deemed necessary to develop another football game for the system (though INTV bought Intellivision assets from Mattel and updated the source code in 1986 to include a one-player mode and released the ensuing game as Super Pro Football). This would have been a difficult challenge at any rate, since years passed before other programmers were able to catch up and provide something even remotely similar on the virtual gridiron.

The groundmark game remains enjoyable even now, via official emulation programs such as Intellivision Lives! for Windows and Intellivision Classics for the Sony PlayStation. Intellivision itself may not have been as influential on the development of video game culture as the Atari 2600, but its legacy of superior sports games endures, particularly in regard to NFL Football.

Super Action Football

Coleco

The next step in football gaming was provided by a company once called the Connecticut Leather Company. Coleco entered the console systems market in the summer of 1982, following a lengthy period on the sidelines after the failure of its Telstar-labeled version of Pong in 1976. ColecoVision arrived in June amidst much fanfare and a number of exclusive, high-profile arcade game licenses that included Donkey Kong, Venture, and Carnival.

Licensing such hot properties and providing consumers with near-perfect home versions of these quarter-a-play favorites made the system a huge early success. Coleco neatly positioned itself to steal customers away from both Atari and Intellivision, the former by grabbing up the licenses that had become its bread and butter and the latter by developing a lineup of premium sports games. The company played on its experience as a manufacturer of top-selling handheld titles, such as Electronic Quarterback and Head-to-Head Baseball, to move into this arena with confidence. When 1983 rolled around, the ColecoVision was rapidly becoming the top system for electronic athletes.

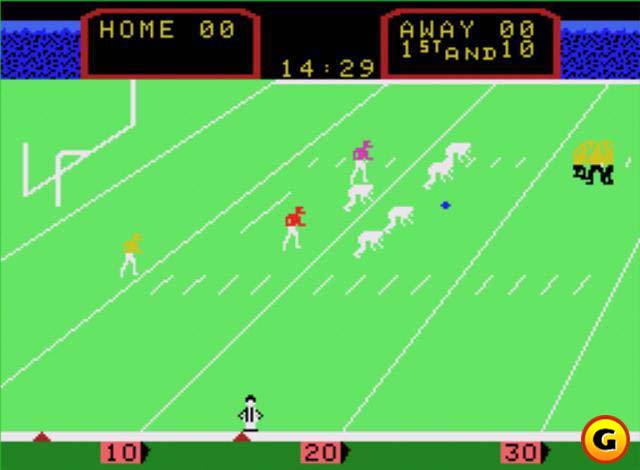

Coleco's "Super Action" series of sports games was anchored by Super Action Football. This title was intended to represent the next stage in football gaming, both as an arcade twitchfest and as a strategic experience. The look of the game was entirely new, shifting from the flat, straight-on camera angle of its rivals to a 3D isometric aspect that gave it more of a TV broadcast appearance. Players were drawn with multiple colors for the first time, and there were more of them than even before--a whopping eight on each side. It even included a little referee in a striped shirt. All the standard football rules and conventions were there, from going out of bounds to kicking field goals and fumbling the ball.

But although Super Action Football looked very good, it wasn't very playable. For starters, it required an added investment in the Super Action Controllers that came with Super Action Baseball. These huge and rather expensive devices were a compromise between the traditional, Atari-inspired joystick and the Intellivision-like standard Coleco gamepad, with a big red knob, a trackball roller, and a keypad topping a base with four trigger buttons. Many found these controllers unwieldy--too large and awkward to properly use. Even those who liked the devices didn't appreciate being forced to buy a separate controller just to play one or two sports titles.

No matter what you thought of the controllers, opinion was generally negative on Super Action Football. Although there were more players on the field, you could control only three of them, as linemen were nothing but immobile blocking dummies. Programmers seemed to have bitten off more than they could chew with the overall visual design, as animation was slow and stuttery. Movement was so clumsy that you spent much of each game wondering if the game was actually responding to how you yanked that Super Action joystick back and forth. To make a running back or receiver run faster, you actually had to spin the roller at the same time that you pushed the stick. It wasn't exactly very easy on the hands. Calling a play was roughly equivalent to that seen in Intellivision's NFL Football--with individual patterns for most players--though the poor controls and animations challenged your patience every time you ran one.

Along with all of its rivals, ColecoVision all but died in 1984 as a result of the video game crash. Despite its exceptional technology in comparison with the Atari 2600 and the Intellivision, the system came along too late to make a significant impact on the evolution of the industry--unless you were a serious fan of arcade ports. In terms of football gaming, ColecoVision is barely remembered at all, aside from its dubious contribution to the history of strange joystick design.

Coleco itself reemerged as a toy manufacturer in the later 1980s and made a mint off the Cabbage Patch Doll craze. This sensation didn't help the company stave off bankruptcy, however, and its assets were sold off to former rival Hasbro in 1989. ColecoVision itself survived the death of its parent, however, and systems and games are still being manufactured and sold online by Telegames.

On-Field Football

Gamestar

Moving into the void left by the video game crash of 1983-1984 was the Commodore 64. The modest computer system replaced consoles for many gamers, mostly because of its versatility. Along with having the capability to play great games, its keyboard and floppy disk drive made it more useful to have around the house than the one-dimensional console units.

Regardless of the added applications, the Commodore 64 became best known in the mid-1980s as a top gaming platform. This was due largely to the great variety of games available, from arcade adaptations such as Ms. Pac-Man and Dig Dug to sports titles such as the renowned Summer Games series and Accolade's revolutionary Hardball. Football was a big part of the latter category, although the sport never achieved the stature of its baseball and Olympic rivals--possibly because there was no single franchise pigskin title on the Commodore 64 for fans to focus on. Still, there were a number of lesser ones.

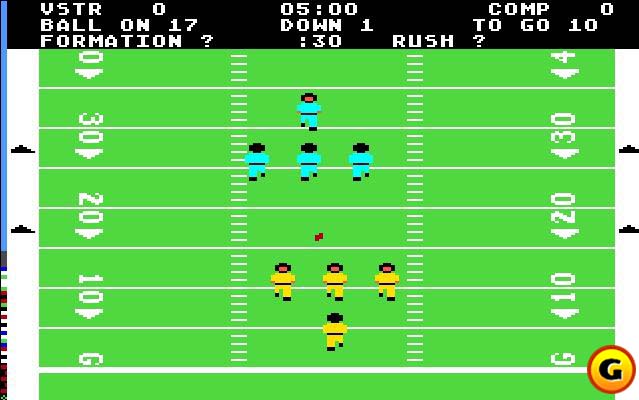

Leading the way was On-Field Football from Gamestar, a company that served as the EA Sports of the Commodore 64 for a time in 1984 and 1985. This game paled in comparison with sister titles On-Court Tennis and On-Field Baseball, though it was still a worthy replacement for the console football titles of the same era. All of the basic rules of the game were respected, although there was the expected reduction in the number of players on each side. Teams were made up of just four players per side, though a certain amount of intrigue and longevity was provided by the ability to choose a starter from the two names listed beside each position. These players were rated in different skill categories that showed up in how they performed on the field, adding an element of simulation to each contest. Playcalling was quite intricate for the time. The many different formations and routes assigned to each player represented sort of a middle ground between the crude efforts of the early 1980s and the more ambitious titles (like 4th and Inches, covered below) coming down the road in a few years.

Visuals were fairly good, but they were still limited in that peculiar way that defines all games designed for the Commodore 64 in the early 1980s. Like the other Gamestar sports titles, On-Field Football used small players drawn with a minimum number of sprites so that animation would be quick and smooth. The overall effect was something that was a long way from lifelike in terms of appearance but somewhat closer to reality in the way that it moved. One of the benefits of this approach was that the models were obviously abstract representations of real football players. Unlike other football games, On-Field Football never attempted to look like the real thing, so the fact that it didn't wasn't so jarring. The setting was equally artificial, albeit in a good way that included stands filled with flashing colors, serving as spectators. A regulation-length field scrolled up and down and included goalposts. On-Field Football served as a nice bridge between the likes of NFL Football for the Intellivision and later games such as Gamestar's own Touchdown Football and GFL Championship Football (which included a revolutionary first-person camera mode and was also released for the Atari ST), as well as Accolade's 4th and Inches (see below). Its numerous innovations, most notably the incorporation of players with variable skill levels, set a standard that would be followed for the remainder of the decade. This also represented a more commercially viable blend between the popular arcade approach to football and the management-style simulations that began to show up for the Commodore 64 and other computer systems around the same time. Titles such as SSI's Computer Quarterback and Avalon Hill's Football Strategy blazed a trail that is still being followed today with the likes of Front Office Football and Action! PC Football.

Great Football

Sega

The great lost gaming system of the 1980s was undoubtedly the Sega Master System. Although it made a promising debut in 1986, thanks in large part to impressive 8-bit technology that dwarfed what had gone before, it was rapidly overtaken by the NES. Super Mario led a craze that made Nintendo the undisputed industry leader by 1988, assuming the same position that Atari had held nearly a decade earlier.

Still, Sega had a brief moment in the sun during the mid to late 1980s. The relatively few games that were produced for the Master System were generally of high quality and were certainly far more complex on average than the kiddie fare upon which Nintendo was focusing. Sports games were a particular specialty. This was an area that Nintendo had not properly explored, so Sega moved into this arena with a fervor. The company developed a line of "Great" sports games encompassing most of the world's major pastimes, including baseball, golf, soccer, and, of course, football.

But Great Football wasn't very well promoted. And like many of the Sega Master System titles, it was inadequately distributed. It was even harder to find than other games from the same series, such as Great Baseball and Great Golf. Perhaps that was a bit of a blessing in disguise, as Great Football simply wasn't much fun to play. It was far less interesting than most titles in the line, like Great Baseball. Some interesting ideas were advanced, and it was nice to know that football could be played on these second-generation console systems, though the overall execution was very poor. Twelve teams from two different conferences were available to choose from, but they differed only in their names and the color of their uniforms. There were numerous passing formations, but no actual plays other than simple runs and passes.

Making plays was nearly impossible, due to the speed of the play and the strange control system. All computer defenders could move at the approximate speed of Ben Johnson before that urine test in Seoul, with the ability to catch ball carriers who were as much as 10 yards downfield. Passing was equally strange. There seemed to be no way to properly aim the ball, so making a simple completion was a struggle all by itself. The developers apparently faked their way through the design process, emblazoning the center of the field with an American eagle as if to hide the fact that they just didn't get what football was all about.

Sega released a second enhanced version of Great Football around the same time. Sports Pad Football offered slightly improved gameplay due to the requirement of special sports pad controllers, though it still wasn't worth the added investment. The sports pad idea died a quick death. Much like the earlier ColecoVision Super Action Controllers, consumers weren't interested in buying special hardware just to play one or two titles. After Sports Pad Football and Great Ice Hockey, the controllers were shelved. Football for the Master System wasn't abandoned, though it probably should have been. Sega licensed the name and likeness of Chicago Bears legend Walter Payton in 1989, but the subsequent Walter Payton Football was nearly as bad as its predecessor. Regardless, by that point, the Master System had already been eclipsed by the NES--and was even being moved to the backburner by Sega itself, which was ramping up for the launch of the Genesis.

4th and Inches

Accolade

A good indicator of how far football game development had come arrived in 1987 with the release of Accolade's 4th and Inches for the Commodore 64. The game took football to a new level, combining the traditional arcade action seen in earlier titles with added elements of strategy. For the first time, a football game was compulsively playable as both a simple twitch joystick experience and as a strategic challenge.

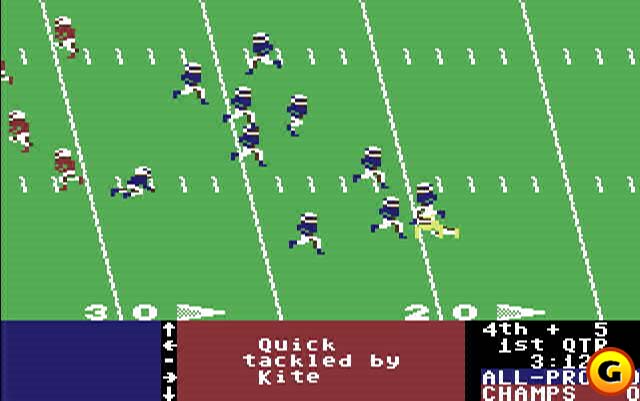

4th and Inches was designed by Bob Whitehead as a companion piece to his earlier take on baseball, Hardball, which was published in 1985. Like Hardball, games were played with red teams and blue teams, which were given the generic names of Champs and All-Pros, respectively (actually, this represented a minor change from the baseball title, as the blue team there was called the All-Stars). A full 11-man squad hit the field for each and every play. There were no substitutions, but each player was given different skills and capabilities. Each club also had a distinct personality. The red Champs were physically stronger, possessing a powerhouse ground game, while the blue All-Pros were quicker and better with the passing game. You had to play to these strengths and weaknesses to have a shot at winning in 4th and Inches.

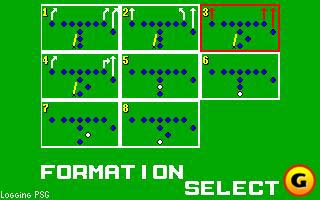

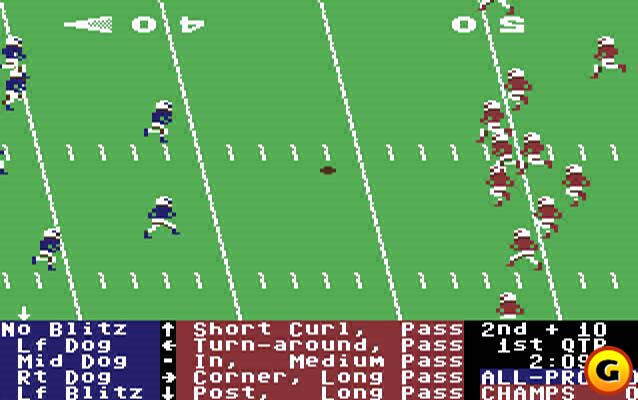

Playcalling clearly foreshadowed what was to come in subsequent football games. You started by designating a formation and then moved on to select an actual play. There were five choices of each every time you entered the huddle, with what you chose as a formation determining what popped up as options for the play itself. These plays were extremely varied on offense, encompassing draws, curls, sweeps, long bombs, and so on. Defense was a little more simplistic, although you still could tailor your formation and assignment for what you thought your opponent was about to attempt. The only real weakness was having to select a running back, receiver, or defensive player to control before the play began and then not being able to switch control during the action. This occasionally left you watching from the wrong side of the field on defense and having to eat the ball rather than throw into tight enemy coverage.

Visuals were understandably crude. The basic act of depicting 11 players on the field sucked up just about all of the resources that the Commodore 64 could call on, so models were little more than stick figures with jittery arms and legs. Even though 4th and Inches came out two years after Hardball, it looked as if it had been designed two years before. It reused many of the sound effects found in its companion game, though, including the national anthem, a white noise crowd effect, and a "Charge!" tune that played every time a team moved into scoring range.

Oddly enough, 4th and Inches never evolved past its beginnings. Unlike Hardball, which became Accolade's flagship series and lasted through six iterations until the end of the 1990s, this game slowly dropped beneath the radar screens. Its fate might have been better if not for the prompt arrival of even better games, such as TV Sports Football and John Madden Football, which pointed more toward the future than the past. 4th and Inches represented a peak of 1970s and 1980s football game design--a worthy achievement, to be sure, but not one that placed in it a good position to prosper as computers became ever more advanced. Accolade itself was bought out by Infogrames in 1999, and the label was quietly retired.

Tecmo Bowl

Tecmo

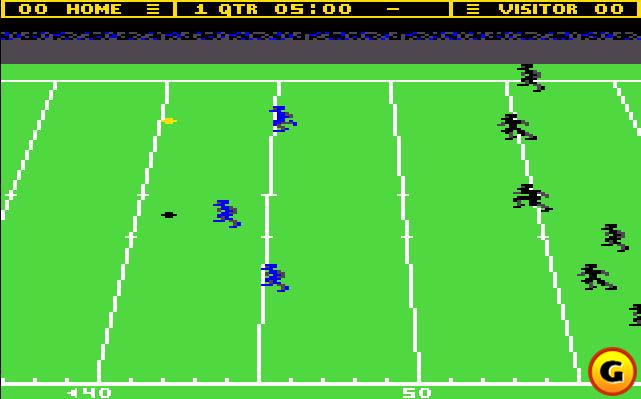

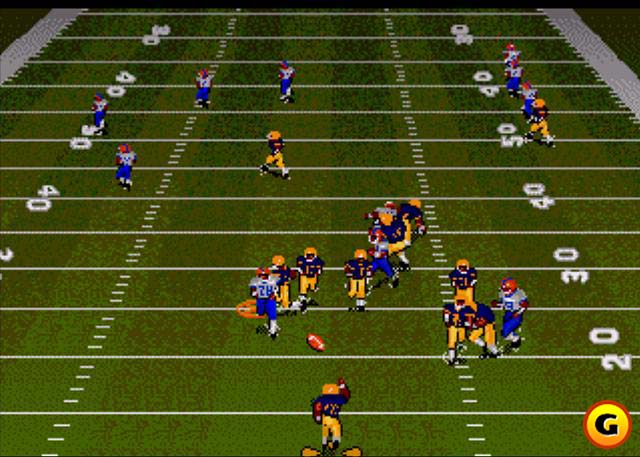

A good representation of football finally came to the NES in 1989. Tecmo Bowl succeeded where earlier efforts had failed, the likes of Taito's 10 Yard Fight being too clumsy to engage pigskin fans for very long. It was also pretty rough and ready, although it generated a lot of simplistic fun that could be appreciated by anyone who enjoyed action games.

Tecmo Bowl added a dose of reality with the NFL Players Association license, which allowed the use of real player names. A total of 21 players were featured on each of the game's 12 teams, including all of the greats of the time, such as Joe Montana, Phil Simms, and Walter Payton. Units composed of just nine men lined up on the field, though, and even this trimmed-down number was enough to cause some serious flickering. Presentation quality was poor for the time--colors were vaguely cartoonlike, and there were no frills, aside from the voice samples of a man shouting "Down!" followed by "Hut!" over and over again every time the quarterback got into place behind the center.

Play emphasized quickness and ease of use over depth. Playcalling was simple enough to be almost nonexistent. You simply picked from one of two running or two passing plays before the snap. These didn't change no matter what side of the ball you were on. Passing plays on offense simply became defensive formations designed to stop the pass. If the defense guessed the correct play, the defenders would immediately smash all the blocking and blow up the play automatically. After the ball was snapped, reality pretty much completely vanished. Players bounced up and down as if they had flubber on the soles of their shoes. The ball arced more like a pop fly than a tight spiral. And points were very, very easy to come by. Whoever possessed the ball last usually won the game.

Even with these flaws, Tecmo Bowl was a blast to play. The snappy gameplay and goofy visuals and sound make it a true retro gamer's delight even today. It remains one of the most popular NES games ever released. Tecmo Super Bowl, a sequel released in 1991, developed even more of a fan following. Comparing the two games reveals an almost stunning advancement in game design and technology. Full league play included 17 weeks of regular season play and then playoff rounds, near-complete NFL rosters and player ratings, and player streaks and injuries. Much better graphics were also tossed into the mix. All of this added up to a remarkable achievement that was unprecedented. Many claim that it is the finest football game ever released for any system, and people actually play it in online leagues even today. It's certainly a must-have for any collector of NES titles.

Tecmo took advantage of this sudden popularity, releasing two limited edition sequels in subsequent years and porting the title to the Sega Genesis, Super Nintendo, and Sony PlayStation and even to mobile phones in recent years. But aside from the nostalgic release on mobile platforms, Tecmo has largely abandoned the franchise and devoted most of its attention to games in other genres like the popular Dead or Alive series of fighting games, and a modern version of Ninja Gaiden.

TV Sports Football

Cinemaware

No football game summed up the progresses of the 1980s like TV Sports Football. For the first time, all of the design conceptions that emerged over the past 10 years were collected into a single game. Cinemaware also introduced a number of innovations. Contemporary technology on the Commodore Amiga and TurboGrafx-16 was pushed to its limits to provide a game that looked great and came packed with depth and management options.

First and foremost, though, was the presentation. TV Sports Football was true to its name in that it adopted a TV broadcast style. Gameplay was bookended by visits to a studio for introductions, previews, and updates, all of which were delivered with a sense of humor. This aspect of the game even included such things as minicutscenes focusing on different parts of the stadium. Right after scoring a touchdown, for example, the camera could pan over to the cheerleaders for a quick look at them shaking their pom-poms. There was even a halftime show.

Visual quality was very high for the time period. The broadcast sequences and cutscenes used large sprites, allowing for colorful and realistic renditions of announcers and players. Everything was just as attractive on the field. Players looked better than ever, decked out in multicolored uniforms and featuring a level of 3D depth that hadn't even been attempted by earlier designers. Animation was fluid as well, an impressive achievement considering the size and detail of the players.

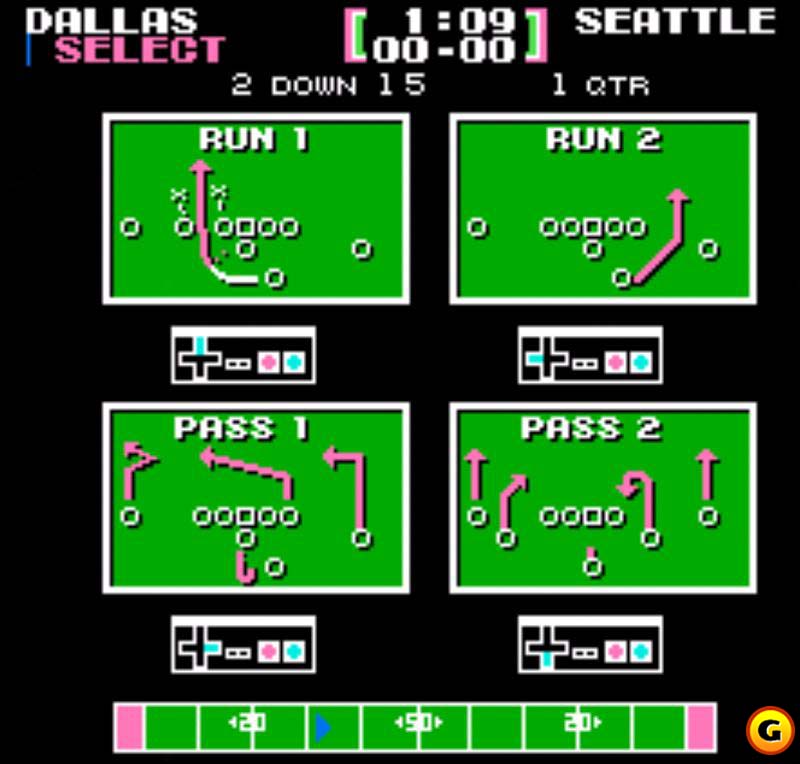

TV Sports Football played as good as it looked. Playcalling was easy and full of options. You could mimic just about anything that a real NFL coach called for on Sunday afternoon. Plays could even be reversed, and a man could be sent in motion. On offense, handing the ball off was easy, but passing was considerably trickier. To pass, you needed to point the quarterback in the right direction and then hold down the joystick button to bring up a green "X" indicating where the ball would be thrown. You could move this target around simply by keeping the button pressed and moving the joystick. When you released the button, you passed the ball to the current location of the "X," and the nearest receiver moved into position to catch it. This method of passing wasn't everyone's cup of tea, though it did provide an extra gameplay challenge.

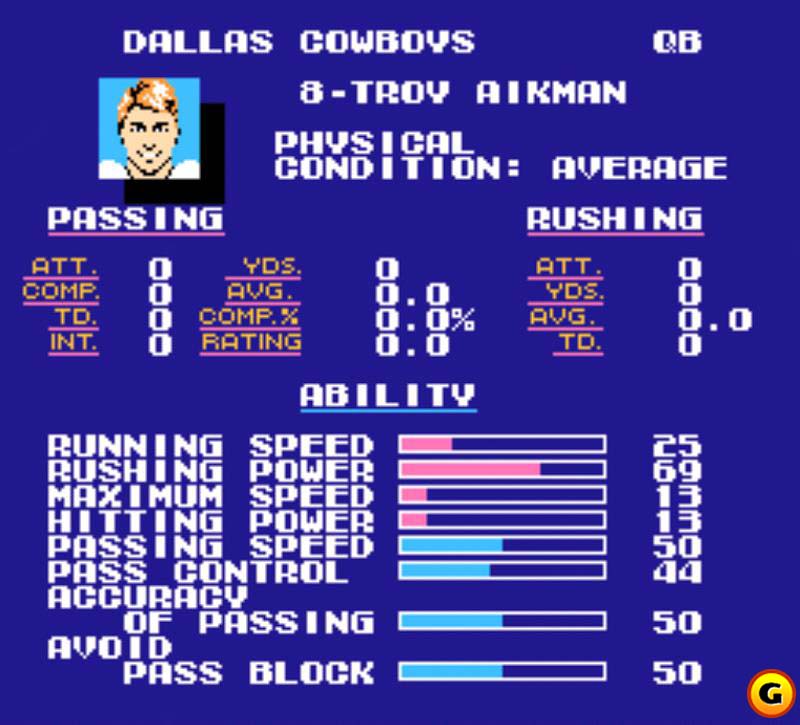

An impressive feature set was more in line with current sports games than those published in the 1980s. Teams were represented by regulation 11-man units on offense and defense, and there were a total of 28 different clubs in the game, each with different playbooks that emphasized their strengths. Cinemaware didn't bother with either an NFL or an NFLPA license, but careful observers could tell who was supposed to be whom thanks to detailed player ratings. These ratings could also be edited, and full season play was supported. Up to 28 human players could choose sides and progress through a 16-game season and playoffs, complete with team and individual stat tracking. There was even a multiplayer option that let up to five players play at the same time, as well as a coaching mode for those who preferred not to take a direct role at all.

In addition to TV Sports Football and TV Sports Basketball, Cinemaware published a number of other critically successful games in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Some of the company's best-known efforts were Defender of the Crown, It Came From the Desert, and The Three Stooges. Critical accolades didn't sell many games, however, and Cinemaware was forced to close up shop in 1991. The company has recently been revived, but only to port its classic titles to the Windows format and replace the older visuals with something more pleasing to the contemporary eye. A revamped version of TV Sports Football was supposedly on the drawing board in the late 90s, though the project never came to fruition.

The Modern Era of Football Games

Along with the rest of the gaming world, the football game came of age in the 1990s. For the first time, steadily advancing technology freed designers to catch up with our imaginations. The immediate result: games that looked and played in a more realistic fashion than ever before. Official NFL licenses became commonplace, as did authentic rosters and playbooks that mirrored those used in the real world. The days of five-man teams and stick-figure quarterbacks were gone for good. Developments with computer graphics boards and the gradual move from 16- to 128-bit console systems permitted the depiction of players who both appeared and moved like the real thing. What we played in 1987 seemed hopelessly out of date as early as 1992.

This new era actually began at the end of the 1980s. John Madden Football debuted in 1989 from Electronic Arts, kicking off a series that would evolve into the Cadillac of sports game franchises over the following decade. Madden soon branched out to most computer and console platforms and redefined sports gaming in every way. First and foremost, it upped the ante on realism. The overall design stressed a genuine version of pro football that made what had come before seem Pop Warner by comparison. Secondly, the successful development of Madden as a yearly franchise changed the way that sports games were marketed. Prior to this, the accepted logic was that you designed and sold one version of a sports game, perhaps augmenting it with a season disc or two. Afterward, the updated iteration of a sports game came out with calendarlike precision, the new title hitting store shelves just before the beginning of the equivalent real-world season. Hindsight has shown this to be a rather dubious achievement, though this hasn't taken away from Madden's impact.

Madden's prosperity spawned many rivals. In an attempt to further cement the reputation of the Sega Genesis as the best platform for sports games, Sega introduced Joe Montana Football in 1990. Early releases in this series offered a cruder version of football than that offered by Madden, though the quality did improve over time. It was also one of the first sports series to offer a lot of bells and whistles. Joe Montana II: Sports Talk Football and NFL Sports Talk Football 93 Starring Joe Montana included rudimentary commentary for the first time in a console football title. The latter boasted more than 500 separate one-liners, a remarkable achievement in the 16-bit era. Sega even branched out into college ball, adapting the Montana engine for use in the Bill Walsh College Football line.

For a brief time, there was a heated rivalry between the Madden and Montana series. Montana eventually lost, though this failure was due more to the rise of the Sony PlayStation as the next big console system than any problems with the game itself. One of the reasons why Sony did so well was that the company capitalized on the need to replace the aging Sega Genesis as the primary platform for sports games. An opening salvo was fired with NFL GameDay, released under Sony's 989 Sports label not long after the PlayStation itself reached stores in 1995. An NFL license, individual player stat tracking, great-looking visuals, and precise arcade control over the on-field action made it a huge hit.

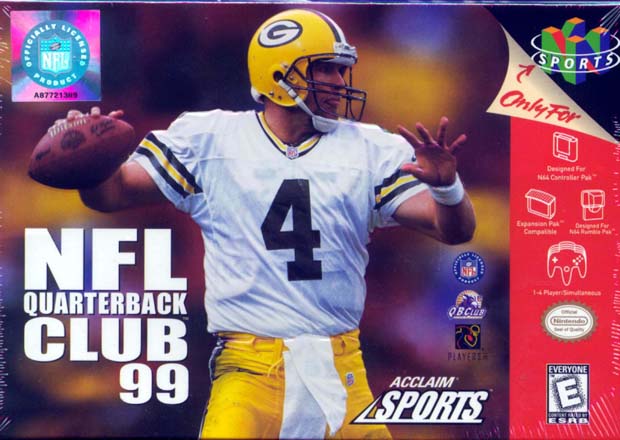

Madden and GameDay seemed content to share the football gaming crown, although they still showed continual subtle improvement to fend off challengers like Acclaim's NFL Quarterback Club. There were some major advancements in the early to mid-1990s, but these were mostly registered on the PC side of things. The full sophistication of the NFL came through for the first time with Sierra's revolutionary Front Page Sports: Football. This series brought the virtual gridiron to a new height, thanks to complex playbooks, exhaustive stat tracking, and the ability to set up customized career leagues with drafts, trades, and retirements. Arcade play on the field was seamlessly blended with management responsibilities. It was the closest that developers had come to putting an NFL franchise in a box.

This raised the bar for everyone. New computer football titles like Accolade's NFL Legends Football 98 and Total Control Football tried to take the idea of a complete football game even further with frills such as historical play and financial management. An audience was also developed for pure management games such as Front Office Football and PC Action! Football. Perhaps more importantly, however, Madden and GameDay extended the simulation aspects of their games and soon added franchise play to their repertoires. With the notable exception of NFL Blitz, arcade sports games as a whole began a shift toward realism. After Front Page Sports: Football showed everyone what was possible, gamers stopped settling for anything less than the whole package.

That philosophy has taken us right up to the present.As football games have evolved, they've certainly piled on the features. New football games released in the past few years have incorporated everything but Don Shula's kitchen sink. Although they vary in their approaches, all have been crafted to appeal to both the action-first gamepad jockey and the cerebral sort that prefers to send in plays from the sidelines. The NFL 2K series, for example, was not only the first console footballer to go online, but also it shook things up with a first-person football feature that put you on the field and in the quarterback's helmet as you attempted to complete passes while eluding defenses. Meanwhile, the short-lived NFL Fever series from Microsoft made waves with its online features. And finally, the Madden franchise has long been know for consistently adding new and interesting angles to the virtual football experience.

It's hard to overestimate the importance of online play to the sports gaming world, and especially to football games. With the vast proliferation of broadband in America over the past decade, it's hard to believe that gamers once actually played multiplayer online football over a simple phone line via the Dreamcast. Ever since, online football has evolved with each successive season, sometimes for the better (such as with the old ESPNvideogames.com Web site that let you track your team and league stats) and oftentimes for the worse (One word: cheesers. For more on this phenomenon, check out the sidebar). While there's still a ways to go in the evolution of multiplayer pigskin (EA Sports still can't seem to get an online franchise mode going), there's no denying that online will play a central role in NFL games to come.

The Price War

Take-Two had relied on the quality of its NFL 2K series as its sole selling point for a long time. Indeed, while the plucky alternative to the more-well-known Madden game was critically lauded, it didn't approach Madden's sales numbers. In 2004, Take-Two made a strategic move to undercut sales of its biggest competitor by dropping the price of its formerly $50 football series to a mere $20. This was followed shortly thereafter by the entire line of Take-Two's sports games being dropped to budget prices.

With little room to maneuver, EA Sports had to react with cost slashing of its own, and even though it took the publisher three months to enact its price drop, it did end up bringing down the price of Madden NFL 2005 to $30 (which was still ten bucks more expensive than its rival) in November, while similarly lowering the cost of select others in the EA Sports stable. Little did the sports gaming world know, but when it came to the burgeoning football wars of 2004, EA Sports had only begun to fight. The biggest blow would come just a month later.

The New Deal

Gamers were preparing for a long winter's nap of rest on the night of December 11, 2004, many with visions of an upcoming holiday break and games of Madden 2005 and NFL 2K5 dancing in their heads. Little did they know that just one day later, the entire landscape of football gaming would change in one fell swoop. Electronic Arts made the announcement that would forever change football games (or at least change them for the next half-decade): The publisher-developer had entered a five-year deal with the National Football League to be the sole developer and publisher of NFL games on all platforms. The deal, rumored to have cost EA around $400 million to secure, would go into effect in 2006. The deal would essentially, and in one motion, knock out Take-Two's NFL 2K franchise, thus killing the idea of the then-recently shelved GameDay and NFL Fever series from returning anytime soon.

This wouldn't be the last of the blockbuster football announcements in late 2004 and early 2005. To give its competitors as little wiggle room as possible in the football realm, the company also tied up the ESPN license for a whopping 15 years (a deal estimated at more than $800 million), it grabbed the Arena Football License, and, just for good measure, it made its de facto status as sole publisher of college games official by wresting the NCAA Football license as well. In theory, EA Sports was intent on becoming the one and only place to get your officially licensed football products for the remaining part of this console generation...and well into the future. And in practice, the company made this happen.

Needless to say, the announcements of these exclusive licensing deals sent shock waves through the sports gaming community. Some cried foul, calling the deals just more nefarious steps in EA Sports' bid for a sports monopoly. Others, including industry analysts, hailed the move as smart business. After all, these were companies in the business of making money, not friends. For its part, EA Sports claimed the move was a direct result of the NFL's desire to make an exclusive deal and that the league had approached several interested corporations to test the monetary and strategic waters. As a league, the NFL has long been a fan of exclusive licenses--from Gatorade to Reebok--and if the most popular sport in America wanted to deal solely with a single game publisher, EA was determined to be that publisher.

With no NFL, AFL, or NCAA licenses to work with, publishers like Take-Two, 989, and Midway were left in a quandary. Could they possibly create a game that would even make a dent in the increasingly popular Madden juggernaut? Furthermore, would dedicating a team of developers to such a product even be worth it if the game was missing the most valuable license in American sports? For a while, the football world was silent, with gamers wondering just who would make the first move and play its hand in this new, higher-stakes marketplace. Rumors began to swirl around Midway. Specifically, they said that the former Blitz publisher was resurrecting its brand of hard-hitting, arcade-style football using the Playmakers moniker (after the short-lived ESPN series about a fictional football league). Soon after, the Playmakers name was dropped, and Blitz: The League was reborn.

Midway finds itself in a uniquely advantageous situation with Blitz: The League. The publisher has an established brand name, one that still holds a degree of nostalgic value, and, to a certain degree, the game works independently of the presence of an official NFL license. After all, over the years, the NFL, in a continuing bid to carefully control its public perception, has kept a tight rein on violence and objectionable content in its games. Unfettered of these constraints, Midway's arcade pigskin game is in as good a position as could be hoped for in this difficult market. Unfortunately, the same can't be said for other players in the game, particularly Sony, which shelved its GameDay series only to follow it up with the ill-advised Road to Sunday.

Over the past four years, the quality of football games has improved, thanks in equal parts to improving technology, innovation, and, at least up until recently, competition. The brave new landscape of football video games has taken a sharp turn, with all eyes focused on EA Sports and its stable of officially licensed football products. Thanks to its savvy business tactics, EA will be the defining voice of NFL games for the next next-generation consoles. You wonder how gamers five years from now--at the tail end of the historic EA-NFL deal--will look back and reflect on this era that arguably began with the Dreamcast and ended in late 2004 and early 2005. The last five or six years have been among the best, most competitive, and innovative in the entire history of football video games. The upcoming era, which encompasses the next five or six years, will be unique for its singular focus on the Madden series as the torchbearer for NFL games, as well as for how the other football publishers will respond to increasingly hostile competition.

John Madden Football

Electronic Arts

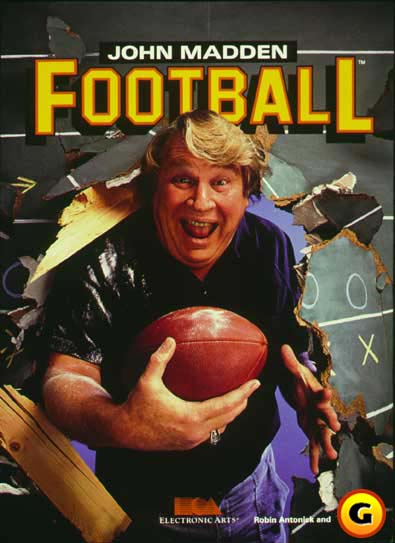

According to legend, the Madden series of football games began with Amtrak. Trip Hawkins, one of the founders of Electronic Arts and an avid sports gamer, first hooked up with John Madden on a train in 1986. The location of the meeting was prompted by the hall of fame coach's fear of flying, a condition that necessitated that he keep both feet on terra firma while traveling to broadcast assignments. Making matters even more uncomfortable was the big man's recalcitrance. He balked at the idea of seven-man football, saying that he wouldn't lend his name to something that wasn't completely authentic. Technological limitations made this impossible at the time, but EA stuck with Madden anyway.

The persistence paid off. John Madden Football--with a full 11 players per side--was released in 1989 for the Apple II computer. This first game served as a launching point that soon propelled the series to other, more enduring platforms such as the Sega Genesis and the PC. Gameplay was rather simplistic at first. Although John didn't want to compromise the number of players on the field, his first game included just 16 of the 28 NFL teams in existence at the time. Most of the heavy hitters were there, the lineup including traditional powers such as Dallas, Washington, San Francisco, Denver, and Miami and dropping weak sisters such as Tampa Bay and San Diego. But the absence of NFL and NFL Players Association licenses meant that these teams lacked the proper nicknames, logos, and players. Playbooks were basic affairs with elementary formations based on the situation (goal line, long, short, special teams, and so on) and just a few plays available for each--although the "ABC" window still in use today was present right from the start. Just three gameplay modes were featured, although these included an intriguing season option and a sudden-death game perfect for multiplayer fun or a quick time killer against the computer.

The series didn't stay primitive for very long. John Madden Football 92, which came out for both the Genesis and the Super Nintendo (though the latter version was inferior at first and would remain so for some time), improved the graphics with visible weather conditions such as snow and rain, added the 12 teams that were missing in the previous installment, and introduced three to four defensive and run-and-shoot offensive formations. EA also took some tips from Cinemaware's TV Sports Football and used a broadcast booth style of presentation that included an announcer from the Electronic Arts Sports Network (or EASN, which lasted precisely as long as it took ESPN to notice it and contact legal representatives) and out-of-town scores. Two versions were produced the following year--a standard John Madden Football 93 and a Championship Edition intended solely for rental, which included EA's take on 38 classic NFL clubs and a pair of All-Madden rosters. Digitized comments from the man himself were featured in both games, along with improved AI and expanded stat tracking.

John Madden Football 94 introduced the real NFL to the series. All of the teams and logos were brought on board, in addition to the 38 great teams from the previous year's Championship Edition and another 12 franchise all-pro rosters. Madden himself replaced EASN's Ron Barr as the broadcast booth host. Larger players used a more vibrant color palette, and enhanced animations were obvious in tackling situations. A significant number of plays were added to the playbooks, although the standard formations were left unchanged. Plays could be flipped now, however, and a bluff option when playcalling let you fake out human opponents. This version likely stands as the best ever produced in the series for the Sega Genesis. Later games were very good, but none wholly matched what the 94 game brought to the table at the time of its launch.

You can't categorize the 1995 season as anything but a step back. While adding the NFL Players Association license with the right to use all of the proper player names on current rosters (and changing the name to a stripped-down "Madden NFL"), EA dropped the classic teams--possibly because they were stocked with retired players no longer represented by the union. At any rate, this was a huge loss to gamers. Making things somewhat better was the optional removal of the passing window, a number of new defensive plays, the use of realistic playbooks, and the inclusion of a depth chart that let you preset substitutions for certain formations. In addition to the standard Genesis and Super Nintendo versions, EA produced Madden 95 for the 3DO console. It didn't exactly set the sales world on fire, though it did give a nod toward the future with highly detailed graphics and the chance to get a closer look at the on-field action. The following year wasn't any better. Production problems caused the cancellation of a planned Sony PlayStation version at the last minute, while the planned first PC edition was postponed until the following year (when it arrived as an incomplete bargain title alongside the full-priced Madden 97). The Genesis held the line, though, and even revamped the playbooks and added a player editor.

Monumental changes got the franchise back on track in the 1997 model year. The series made a strong debut in late 1996 for both the PlayStation and the PC, with fantastic visuals that included video introductions with the entire Fox TV broadcast crew and a 3D graphics engine on the field with motion-capped players. Classic teams made a return as well. Playcalling was similar to that seen on the Genesis in prior years, though on-field strategy was augmented with a complete management suite. The whole package was tarnished somewhat with spotty AI, which made the computer extremely vulnerable to the long passing game. Genesis, Super Nintendo, and PC versions were also produced, though most of the attention was deservedly on the PlayStation game. Madden 98 spread the series to more systems than ever, different versions of the game coming out for the Genesis, Super Nintendo, Saturn, Nintendo 64, PlayStation, and the PC. AI improvements were the biggest change witnessed, making the computer much more of a credible opponent, particularly on the PC. This would prove to be the series' swan song on both the Super Nintendo and the Genesis, though the second release for the PlayStation and an impressive Nintendo 64 debut showed that the torch was being passed to good hands.

Cutting back to just PlayStation, Nintendo 64, and PC editions of Madden 99 allowed EA to improve overall quality even more. A good 3D card allowed PC gamers to experience one of the best-looking titles on the market, complete with detail right down to the rolls of fat on a lineman's belly. Players could finally take control of their favorite clubs over multiple seasons in franchise mode. The designers finally reacted to 989 Sports' NFL GameDay and improved control response and the available moves, making for on-field action that felt a lot like the real thing. If you weren't comfortable with all this gamepad mashing, the one-button option let you break the thing down to the basics. Efforts in the following two seasons amounted to little more than treading water. Both the PlayStation and the Nintendo 64 were nearing the ends of their respective life cycles, so the versions produced for those systems seemed a touch behind the times. Things were perhaps a little better with the PC, although the quality there went down in 2000 before rising again in 2001.

In 2000, Madden celebrated its 10th anniversary, as well as its chart-topping 13 million games sold. And there are no signs that the powerhouse franchise is slowing down. That year saw the release of undisputedly the best version of the game ever on both the Sony PlayStation 2 and PC. Adjustable AI sliders made Madden 2001 fully configurable, enhancing play for anyone that felt the default settings weren't quite accurate. The 2002 season featured another outstanding addition to the series for the PlayStation 2, although PC gamers were somewhat annoyed that all they received was a year-old port of the first PlayStation 2 effort. Madden 2002 also marked the first appearance of the series on Microsoft's Xbox console, and though the debut didn't exactly set the world on fire, it was only a matter of time (three years, actually) before the maker of the black-and-green console and EA Sports finally put their differences aside and made nice. Up until Madden 2005, networked play had been strictly reserved for the burgeoning PlayStation 2 set, and if it took a few years before the publisher worked out all the kinks (a process that still continues today), it was clear that making sports games without some sort of online presence would no longer be acceptable in the modern-day sports gaming world.

With the NFL Fever series struggling to get a foothold on the Xbox, and with the NFL 2K series making solid appearances on both the PlayStation 2 and Xbox, the 2003 and 2004 entries of Madden really found the series hitting its stride on the next-generation consoles. Veteran ABC commentator Al Michaels made his debut in Madden 2002, replacing John Madden's longtime companion in both the real and virtual booth, Pat Summerall. The following year saw the debut of Madden 2004, a game that will likely be remembered for the incredible playmaking abilities of the game's cover star, Atlanta Falcons' quarterback Michael Vick. Vick was darn-near unstoppable in the game, a fact that irked many online players searching for opponents whose strategy consisted of something more than simply calling QB draws or rollouts and letting virtual Vick take over the game. The irony? Vick fell victim to the so-called "Madden curse" during his cover-athlete season, suffering a broken leg and only starting four games that year.

This importance of online play was no more apparent than in the full-scale makeup session staged by Microsoft during E3 2004. After trotting out the likes of Carmelo Anthony, Muhammad Ali, and Madden 2003 cover star Marshall Faulk onstage, the announcement that football gamers had been anticipating for months, if not years, was made: EA would bring Madden (along with a host of other games) to Xbox Live. It wouldn't be the only big change for Madden 2005, because, after years of focusing its development efforts on the offensive side of the ball, it was time, it seemed, to get the defense involved. This was true not only of the cover star, Baltimore Ravens legendary linebacker Ray Lewis, but also of a new spotlight on defensive controls in the game. By making use of the right analog stick, dubbed the hit stick, players could finally have a modicum of control over making big defensive plays, mostly in the form of laying out a ball carrier with a vicious hit. The ability to make subtle and effective defensive adjustments using the defensive hot routes, a feature bolstered by the game's ever-improving defensive AI, gave further credence to Madden 2005 being one of the best-playing games in the history of the series.

As tough as the competition was on the gridiron in Madden 2005, the battle between EA Sports and its toughest sports business rival, Take-Two, came to a head when a pricing war broke out between the two companies. Take-Two's move to price its line of ESPN sports games, including the popular ESPN NFL 2K5, to a mere $20 was a hard shot across EA Sports' bow. The publisher-developer reluctantly reacted by slashing the price of not only Madden, but also several games in its sports lineup. As is the case in any price war, the sports gaming fan was the big winner during the pricing tiff between the two companies. Little did anyone know, however, that EA had plans for a much bigger strategic reaction to this market incursion by its competitors. In December of 2004, EA dropped the bomb--by way of a newly minted agreement with the NFL--that EA Sports would be the sole publisher of NFL games for the next five years. That deal was followed up shortly by another licensing blow that would rock the sports gaming world, a mammoth 15-year deal between EA Sports and ESPN. In the span of these two announcements, EA Sports had flexed its considerable financial muscle and had claimed sole rights to not only the most important and lucrative American sports license, but also the biggest name in sports broadcasting in the country. More importantly, it had snatched both away from the hands of its direct competitor, a strategic move we're still feeling the effects of today.

Outside of this cutthroat business, EA Sports found time to offer up a unique vision of the game of football: the brightly-colored, arcade-inspired NFL Street series. Developed by the EA Sports Big crew, NFL Street was equal parts backyard football, urban machismo, and fast-paced seven-on-seven action. Real, recognizable NFL personalities (there are no helmets in streetball, after all) mixed with fictional street pigskin players to create an arcade football game that had the same hard-hitting arcade action of Blitz, though without the kind of objectionable content that would draw the ire of the NFL. 2004 saw two NFL Street games, as the sequel dropped to retailers a mere 11 months after the original. A PSP game based on the sequel, featuring online play and more minigames (and atrocious load times), arrived in early 2005. No subsequent NFL Street games have been currently announced, but, considering EA has to pay for its NFL-exclusive license, we expect that won't be the case for long.

Which brings us to 2005 and the just released Madden NFL 06... Just as Madden 2005 reintroduced the gaming world to defense, Madden 06 takes a fresh perspective on an aspect of the series that hasn't changed in a decade or more: the passing game. By implementing an illuminated passing cone that represents each quarterback's specific cone of vision (and is tied to his particular awareness rating), the publisher-developer is adding a new layer of complexity and, in theory, depth to how things play out on the virtual gridiron. Among its other new features, Madden 06 features an entirely new method of playing the game: NFL superstar mode. This is a feature that puts you in the driver's seat of your own personal NFL rookie as you take him from spring practice, through the NFL Draft, and on to a career as a superstar athlete...with all the on- and off-the-field perks and pitfalls that surround being a pro football player.

With a stranglehold on all things football (the publisher has also signed exclusive agreements to solely publish both NCAA and Arena Football League games), where does EA go from here? While it's far too early to speculate on where Madden NFL 07 will head (Oh hell, a little speculation can't hurt. We'll call our shot here: The cover athlete for Madden NFL 07 will be Miami Dolphins' running back Ronnie Brown.), we do know that the Madden series has a very important stop to make even before details on the 2006 version of the game come to light: next-generation consoles.

Details on the next-gen versions of Madden are scarce at this point. Beyond a cool-looking commercial aired during the 2005 NFL Draft and a brief glimpse at the incredible graphical quality of the game at this year's E3, we don't know what to expect from the game. The commercial seemed to hint at some new directions for the menus and playcalling systems for the game, and you can expect plenty of camera angles and broadcasting tricks that make the most of the game's stunning visuals. Will the game use the passing cone, offensive truck stick, and NFL superstar mode, all of which are new features in this year's Madden game? Will it be a slimmed-down version of Madden 06 that's been designed to whet our appetites for next year's main course? Or will we be treated to modes and features that are entirely new...ones that make use of all the unique hardware capabilities of the next generation of consoles?

One thing we do know for sure: The mighty Madden brand name is in it for the long haul. EA announced in its most recent earnings call that it's signed a 12-year deal with John Madden to use the venerable coach's likeness and name for its football series. As for other questions regarding the next generation of Madden football games, the Xbox 360 launches in the fourth quarter of this year. So we should have our answers soon.

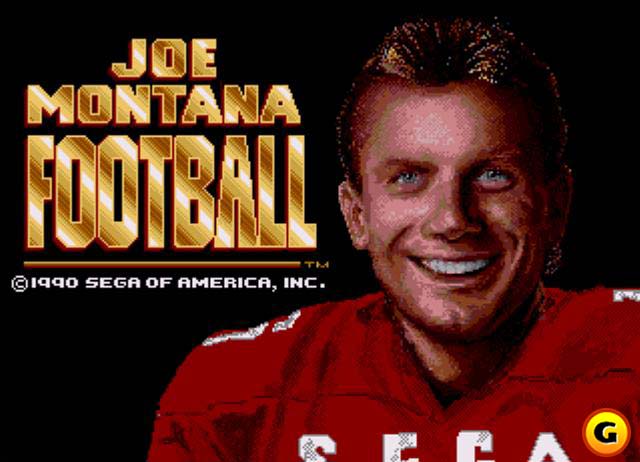

Joe Montana Football

Sega

The finest quarterback in NFL history finally lent his name to a football game as he was nearing the end of his career in 1990. San Francisco 49ers great Joe Montana signed on the dotted line with Sega that year, and the result was one of the longest-running console football series of all time. Joe Montana Football and its successors helped establish the Sega Genesis as the premier 16-bit console system on the market, particularly for sports gamers.

Such a move likely hadn't been planned. Joe Montana Football was actually designed to appeal to sports gamers across the board, coming out in 1990 for numerous platforms, including the Genesis and the PC. Its biggest impact was as a Genesis title, however, the series surviving into the late 1990s despite direct competition from the Madden line. Initially, there was no comparison. The first Joe Montana Football was little more than an updated version of the atrocious Great Football and Walter Payton Football for the Sega Master System (see Part I of this feature). It was particularly weak on the PC, hampered with buggy code, awful graphics that incorporated an annoying side view of the field, and a playbook that was nearly nonexistent.

Nothing in the original suggested that a sequel was anything but a losing proposition, though Sega commissioned one regardless. The resulting Joe Montana II: Sports Talk Football was a minor hit for the Genesis in 1991, however, thanks in large part to the use of a continuous audio commentator for the first time. This synthesized play-by-play man would use basic one-liners such as "The blitz is on!" and "First down!" to describe events on the field during every play. Though the vocal quality was crude, it added a broadcast sheen to gameplay that hadn't been previously attempted. Other aspects were similarly advanced. The playbook boasted more than 50 plays, the in-game camera zoomed in and out during the action when appropriate, and you could team up with a friend to take on the computer.

Sega acquired the NFL license the following year and changed the name of the series to NFL Sports Talk Football 93 Starring Joe Montana. Voice samples soared to more than 500 in the first sequel. Using this as a selling point faded in subsequent seasons, however, as did the aging Joe Montana's effectiveness as a pitchman. NFL Sports Talk Football Starring Joe Montana soon became simply "NFL" with the appropriate year tacked on to the end. Game series quality hit the skids at the same time as Joe's completion percentage went south in Kansas City. NFL 94 had some good qualities, including refined zooming-in during play, but NFL 95 seemed unfinished, with choppy graphics and lots of slowdown.

The series limped on to an ignominious death with NFL 97 for the soon-to-vanish Sega Saturn. This horrible effort single-handedly drove a number of Sega fans into the arms of NFL GameDay and the Sony PlayStation (see below). But there was one positive: As bad as NFL 97 was, it didn't scare Sega away from football games altogether. NFL 2K for the next-generation Sega Dreamcast console system made it clear that the company still had what it took to create an excellent gridiron simulation.

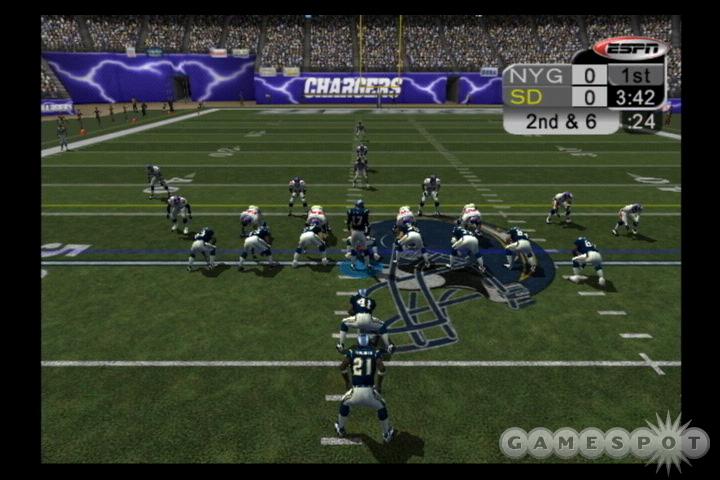

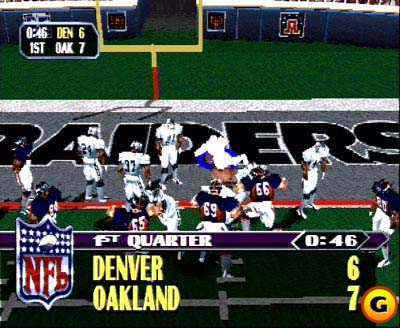

NFL 2K

Sega returned to football gaming in a big way in 1999. As part of the launch festivities for the company's heralded next-generation Dreamcast console system, NFL 2K was released. Indeed, the game hit shelves with almost as much fanfare as the system received, with preview buzz all but proclaiming that this would be the best football game of all time.

Those pundits weren't far from the mark. Though die-hard Madden and GameDay addicts might still defend their respective series of choice as the ultimate in football gaming, critics were simply blown away by NFL 2K. We awarded it one of the highest review scores ever awarded at GameSpot--Ryan MacDonald gave it a lofty 9.9 along with bushels of praise for every aspect of gameplay. This score was well deserved. NFL 2K captured the real NFL in a game in a way not seen since Front Page Sports: Football Pro 95 (see above). Computer AI was tremendous. Each of the clubs came with custom playbooks that they used to the hilt, playing up their strengths and attempting to hide their weaknesses in the same fashion that their counterparts did each Sunday afternoon in the real world. Meaning that you could expect a shootout in games against the St. Louis Rams and a low-scoring, ground-control affair when up against the New York Giants. Every team displayed characteristics that were fully discernible by any follower of the real NFL. And better yet, all of the teams displayed smarts when it came to clock management. Watching the computer quarterback take a knee in the dying seconds was a satisfying sight--even if you were on the short end of the scoreboard.

This accurate "feel" was further accentuated with a precise control system. Gamepad response was excellent, a quick tug on the analog stick allowing you to move players exactly where you wanted them to go. Full use of the Dreamcast controller's buttons allowed the full range of motion on the field, incorporating stiff-arms, jukes, and jumps into every player's repertoire. Visual detail reached an unprecedented level of expertise. Players were given the recognizable faces of their NFL inspirations and motion-capped animation that gave each game the appearance of a TV broadcast. Plays even withstood the "slow-motion test." You could take a close-up look back at every play without seeing anything out of the ordinary. Unlike editions of Madden released around the same time, balls were handed off, thrown, and caught exactly according to the laws of physics. Stadiums were modeled after the real thing, with each park having the proper artwork and fans along with team-specific signage. Play-by-play commentary reached a new height. The no-name broadcast team may have lacked the Fox TV glitz of John Madden and Pat Summerall, but it made up for its anonymity by nailing nearly every play with dead-on observations. Specific, varied references and quick response time sold the illusion that you were listening to real people commenting on a football game.

The evolution of 2K

Unfortunately, NFL 2K didn't launch the football gaming juggernaut that was expected of it. NFL 2K1 came out as planned--and was even an improvement upon its predecessor--but the Sega Dreamcast that hosted the series bombed at the sales counter, failing to make much of an impact against Sony and Nintendo. As a result, the system was shelved at the beginning of 2001. Games would still be produced for the platform for a limited time, though it soon became obvious that such support would be minimal. Although Sega did release NFL 2K2 for the Dreamcast in the fall of 2001 (and used the game engine again in a sister title, NCAA College Football 2K2), it failed to make much of an impact. Months after the Dreamcast release of 2K2, PlayStation 2 and Xbox ports of the game were released on a staggered schedule (with the Xbox version hitting stores just before that year's Super Bowl). Though neither version managed Madden-level numbers, the debut of the 2K franchise on non-Sega consoles was a significant improvement.

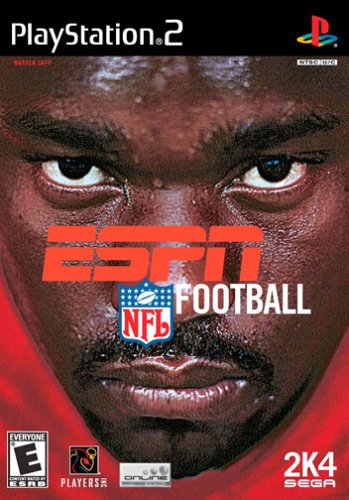

2002's NFL 2K3 for the PlayStation 2, Xbox, and GameCube (incidentally, the only Cube appearance for the franchise) brought the series to a new level of quality. The features that had made the game so great on the Dreamcast, such as the excellent gameplay engine, wonderful sense of presentation, and great game modes like online play and franchise, were refined to a brilliant level of quality. Though the GameCube lacked the online (as did the Xbox version, at least for a short while after its release), all three versions of the game were just as polished as the other. Furthermore, 2K3 marked an important debut for the franchise: namely, the addition of the official ESPN license. Though the presence of the ESPN name and branding was only really noticeable in text menus and on in-game stat overlays, it gave the Sega brand of football something it had lacked when compared to EA's game: a real-life sports name to help lend credibility to the franchise. To some degree, it worked, as sales continued to improve over the previous year's iteration. Sadly, Sega was still getting spanked badly by Madden.

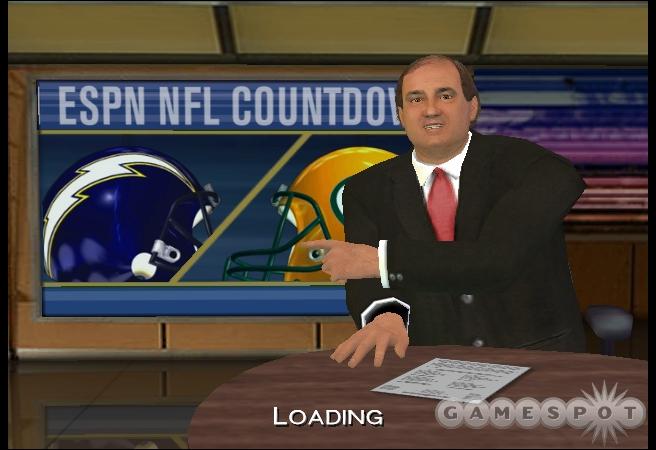

The ESPN branding officially became Sega's baby in 2003, when ESPN NFL Football was announced. Opting to drop the 2K name from the title (but still keeping it on the box in a less-than-prominent fashion), Sega's ESPN NFL Football was designed to be a different kind of football game. Once again including all the features that Sega fans fell in love with, this game brought to the table brand-new methods of play--some good and others...well, others not quite so good. "The crib" introduced a sort of hub area that was filled to the brim with unlockable football paraphernalia, trophies, classic players, and even some crazy, classic Sega music from games like Jet Set Radio. Though the usefulness of collecting posters and other weird bric-a-brac is debatable, many of the other collectibles were a welcome addition, adding plenty of extra value to the package.

The other big debut, however, wasn't quite the slam-dunk feature that Sega seemed to be hoping for. Going so far as to announce this new mode at a special press event at the ESPN restaurant in New York City, Sega's highly touted first-person-football mode just didn't quite come together as well as it could have. ESPN NFL Football wasn't the first game to feature a first-person-camera option to try to give players the sensation of actually being on the field, but it was the first to make a whole bloody mode out of it. The controls were different from a typical game, and the handling of the players also took quite a bit of getting used to. To its credit, the mode really did give you a sense of what it's like to be on the field, with defensive linemen staring you down and the cacophony of the crowd surrounding you wherever you turned. Unfortunately, it just wasn't a great deal of fun. The running and return games weren't half bad, as it wasn't too difficult to try to weave your way through defenders, but everything else was just confusing. The passing game was just a giant pain in the ass thanks to the weird camera shifts, and defense just didn't have a whole lot going on.

Between the lackluster marquee feature, the all-new branding, and a downright scary box cover (featuring the glaring, monstrous eyes of cover boy Warren Sapp) ESPN NFL Football tanked in sales. Perhaps 2K fans just weren't informed about the name change, or perhaps people just had too many bad memories of Konami's thoroughly atrocious ESPN NFL PrimeTime. Whatever the case, Sega ended up giving a lot of ground back to Madden.

A new publisher

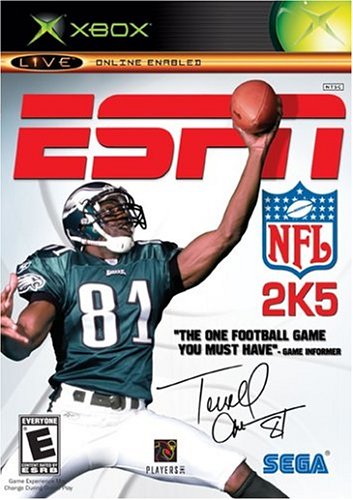

Things looked grim for Sega's sports division, and rumors swirled about developer Visual Concepts. Would it be shut down? Would it get sold off, possibly to EA? Finally, a ray of hope arrived in the form of publisher Take-Two Interactive. In a deal announced shortly after E3 2004, Sega and Take-Two announced a partnership that would have the newest entry in the franchise, ESPN NFL 2K5, distributed through Take-Two's budget arm, Global Star Software. But with that announcement came more rumors and speculation. Not long after the release went out about the deal between the two publishers, major online game retailers began displaying a new price point for ESPN NFL 2K5: a ridiculously low, low price of $19.95. That's right, 2K was going budget. Visual Concepts confirmed the price change not long afterward and also soon announced that for the first time in as long as anyone could remember, the game would be shipping well before its archrival, hitting stores a full two weeks before Madden would be available. Between the price drop and the bumped release schedule, fans, critics, and, most notably, EA, could no longer ignore 2K football, as Sega and Take-Two came out swinging.

The resulting game was no worse for the wear, bringing out another excellent round of football, once again jam-packed with great features. Sure, first-person football was still kind of lame, and the addition of weird D-list celebrities (like Carmen Electra and Steve-O) was beyond stupid, but the additions for the better far outweighed those for the dumb. The ESPN license had been implemented even more brilliantly this time around, bringing such personalities as Chris Berman and Suzie Kolber to life (or, at least, polygonal life) with digitized versions of them that appeared for pregame and postgame analysis. More ESPN commentators, such as Trey Wingo and Mel Kiper Jr., also lent their voices to the game. The franchise mode was the deepest and most involved one the series had ever attempted, giving unprecedented levels of control over coaching, finance, and all the other little trials and tribulations in the day-to-day ops of a professional club.