Faster Harder More Challenging GameSpotting

This week's themes include, but are not limited to, independent game development, construction, yelling at your TV, and bad, bad games.

Welcome to the latest edition of GameSpotting, which is a lot harder than the last edition of GameSpotting, though we still say @!#?! whenever we get hit on the head. This week's themes include, but are not limited to, independent game development, construction, yelling at your TV, and bad, bad games. Feel free to dive in wherever you like, and remember that you can always go to our forums to comment on the feature or read up on the GuestSpotting FAQ for details on submitting your own column for publication.

Greg Kasavin/Executive Editor

"If you want to make games for a living, there's nothing stopping you from starting to learn the trade right this second."

Ryan Davis/Associate Producer

"The days of the video game artisan are long behind us, and every day the production of a video game becomes the collaborative effort of a larger and larger group of people."

Tim Tracy/Senior Producer, GameSpot Live

"I apologize in advance if this column is a little short, but you know what they say about a picture being worth a thousand words."

Tyler Winegarner/Associate Producer, GameSpot Live

"If I get to be that much of a jerk, then that's just icing on the cake."

Jason Ocampo/Associate PC Editor

"In other words, PC market share actually shrank from the previous year. That is really alarming news."

Alex Navarro/Assistant Editor

"I suppose there is no denying that I do get more than the lion's share of the truly awful stuff."

Adam Buchen/Editorial Intern

"From a videophile's perspective, this generation of consoles has really been somewhat disappointing."

Nick Mendez/GuestSpotter

"Why is it that countless people actually pay money to manage another, virtual life, which sucks hours out of one's day?"

John Q. Gamer/GuestSpotter

For many of us, video games are more than just a hobby. They're a fundamental part of our lifestyles. If you've got something to say about games, gamers, or anything related to electronic entertainment, read our

| Greg Kasavin Executive Editor |

Starting Small

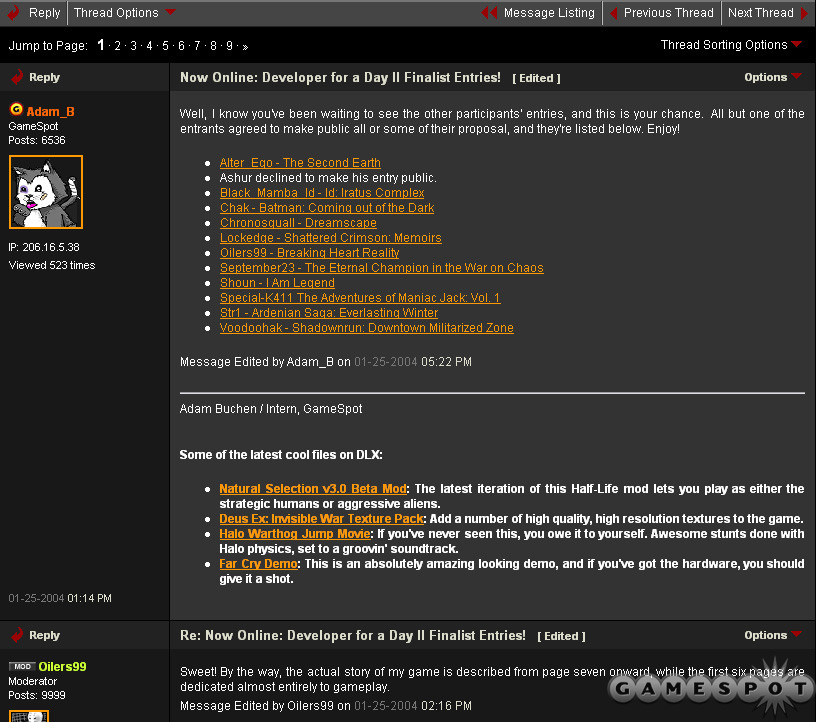

Some of the most interesting reading on GameSpot right now was never even promoted on our home page. It's an informal contest organized by our intern, Adam. As the name suggests, Developer for a Day 2 is actually the second instance of this contest. Basically, it's an open invitation to anyone perusing GameSpot's forums to submit their best idea for a game, as clearly as possible in writing, for consideration. Finalists are selected based on certain criteria, including their originality, the organization of the document, the depth and perceived viability of the concept, and more. Adam personally grades each of the finalists on each of these criteria and then offers them another week to optionally revise their concepts. Then, the finalized entries are put on public display and are also submitted to a number of judges, mostly consisting of GameSpot editors. The judges will end up choosing a single winner (as well as some runners-up). That individual will get $200 of Adam's hard-earned money in exchange for his or her hard-earned accomplishment.

I sense that Adam's enthusiasm for this contest is matched only by that of the dozen finalists he chose. All these people are probably either still in school or have jobs completely unrelated to game development. They presumably have no previous experience working on games. But they play a ton of games, think critically about them, think maybe they have what it takes to contribute to a game development project, and want to start somewhere. They'd at least like to try to get a sense of what it might be like. Admittedly, I am reading a lot into the contestants. But I got the impression from reading the finalists' entries and from observing their follow-up discussions and honest peer-to-peer critiques of one another's work that they're quite serious about this. So, will any of these contestants go on to become the next Will Wright or Hideo Kojima?

I'm getting ahead of myself. What the pending results of this contest reinforce for me is that there seems to be a strong demand for new ideas among people who actively play games, to the point where some of those people are willing to formulate those ideas as clearly as they can and then set them loose on the Internet--the act is like blowing on a dandelion. Something might come of it. You never know unless you try, and all that.

Each of the dozen contestants has his or her own unique motives for being in the contest, but I suspect that the prize money isn't the main attraction for those who've come this far. I'm not sure if any of the contestants honestly believe that they'll get to follow through with their game ideas, but my guess is that these guys would rather get their ideas out there than keep them bottled up. Maybe they fantasize about having their ideas stolen by a big game publisher. Ultimately, they just wish they could be playing these games they've dreamed up.

Recently, Ryan Davis and I had a discussion about how it seems to be increasingly less viable for independent game developers to accomplish anything or to get noticed. The typical game development project incorporates maybe 50 people and demands a few million dollars' worth of costs--not the kinds of resources available to the average person. Ryan understandably seems a bit disheartened as the gaming industry's rich get richer and its poor get absorbed. Are all the original ideas going to be limited to amateur contests on gaming message boards?

No, I don't think so. Even as many small developers are getting swallowed up, tons more are emerging--some of them, rather prominently. Off the top of my head, here are a number of brand-new, very promising game-development houses based in the United States: InXile Entertainment, Obsidian Entertainment, Flagship Studios, and Ready at Dawn Studios. These are founded by industry leaders and veterans. Their staffs include talented and highly experienced programmers, artists, and business people. I have every confidence that the motives behind the forming of each of these companies are good and pure--these people want the freedom to make very high-quality games on their own terms. They have the resources to at least start working on those games. They are willing to assume all the risk, because they are confident. Later, they can partner with a publisher looking to see the project through and share in the reward. The contestants of Developer for a Day 2 probably have a deep respect and maybe a little envy for these sorts of endeavors.

Meanwhile, what the contestants of Developer for a Day 2 have accomplished is that they've acted on an impulse: They've committed what they honestly think is a good idea to writing. Which really isn't much, but then again it's more than most people get done in a day. And that can be a satisfying accomplishment if you're "quite serious" about something, as I said earlier. But not if you're very serious about it.

The would-be game designer has many outlets to begin plying the trade in his spare time. There are countless powerful, freely downloadable scenario-editing tools for the most popular genres of gaming just sitting there and waiting for you to try them. If you want to make the world's next great role-playing game, why don't you start by putting together a decent module in Neverwinter Nights? If you think real-time strategy games need to take the next step and you think you know how they can do it, why don't you try building a campaign in Warcraft III? If you think Max Payne 2 could have been much better, why don't you change the rules? You can. You don't need to be a programmer, and you don't need to be an artist. You don't need to be rich. You don't need to be unemployed and have nothing but time on your hands. Get home from an honest day's work, download or install the program, and start messing with it. Read some message boards. Others are more than willing to impart their immense experience to personally help you. You don't need to pay a red cent for any of it.

The saying goes that the longest journey begins with a simple step. I'm asked all the time how to break into the field of game journalism. I say, get an education and immediately start writing about games, if you haven't already. This industry is filled with people who fell into it and don't really want to be here, and you can help drive them out. I don't actually know anything about how to make games--I merely presume to--but my presumption is that the same advice carries over. If you want to make games for a living, there's nothing stopping you from starting to learn the trade right this second. And always bear in mind that the greatest game designers the world has seen thus far have all been self-taught.

| Ryan Davis Associate Producer |

The Price of Independence

So, last week, while everyone was busy questioning Nintendo's sanity, a little tidbit of news crept out revealing that Electronic Arts would be publishing the next installment in Criterion's Burnout series. My initial reaction was that this was a good thing. I've long felt that Criterion hasn't really gotten the respect it deserves, and getting published by a company with some real muscle could help it get recognized for its efforts. Rereading through the actual news story, I found the one thing that an EA rep was actually willing to say on the record to be a little distressing: "Burnout is the working title of a project in EA's London studio." I interpreted this as meaning one of two things. One, Criterion has nothing to do with Burnout 3 and has handed development duties over to one of EA's internal teams. Two, EA has simply swallowed up Criterion, and a press release announcing the purchase is nigh.

I had GameSpot's resident news Viking Tor Thorsen look into the matter, and Criterion claims that it is developing the next Burnout game, and EA has not bought up the studio. This put me a little at ease, but I still couldn't shake the thought that, sooner or later, Criterion would lose its autonomy and turn into one of the dozens of internal development houses in EA's stable, right alongside the likes of Maxis, Westwood, Origin, Bullfrog, Headgate, Tiburon, DreamWorks Interactive, and Black Box, to name a few. The Burnout story, which coincidentally came on the same day as news of the defection of Free Radical Design's TimeSplitters series from Eidos to EA, got me thinking about the future viability of independent game development.

Electronic Arts is the 900-pound gorilla of the video game industry. Actually, to make the analogy more accurate, Electronic Arts is the 900-pound cyborg gorilla with laser eyes and machine gun hands and twin shoulder-mounted rocket launchers sent from the future to take over the video game industry. There is no other publisher with anywhere near the market leverage or internal development resources wielded by EA--not even close. And while I do regard the monolithic stature of the Electronic Arts organization as a bit frightening, I also recognize the level of quality that EA has fostered in its games in recent years. 2003 was a phenomenal year for EA, and I consider the EA-published Tiger Woods PGA Tour 2004 and SSX 3 to be two of the most expertly crafted games I've played in years. Ironically, though, much of EA's success as a big business can be credited to the A-list third-party developers that it has bought up or made deals with over the years.

It's nice to think of video games as the film industry's kid brother who just went through a growth spurt, and on the big-business end of the spectrum, there are a lot of similarities in the processes that drive the two industries. Whether you're filming The Return of the King or developing Halo 2, you're basically leveraging existing assets and coordinating talent--which, for the laymen out there, translates into spending money and hiring people who know what the hell they're doing. But on the low-budget/no-budget independent level, these are two entirely different worlds. Independent filmmakers can put their friends in a convenience store, out in the woods, or even in a little black box and make a movie that will be seen by audiences at Sundance or Cannes.

This is a criminally simplified look at the process, to be sure, but the road for an independent game developer is far more treacherous. For the indie game developer, the friends, the convenience store, and the woods would all have to be built from the ground up--modeled, textured, and animated from essentially nothing. The closest equivalent an indie game developer without a publishing deal has to the increasingly massive and influential film festival circuit is the Independent Games Festival. The biggest game to come out of IGF was Nexon's massively multiplayer online strategy game Shattered Galaxy--a good game that managed to get commercial release and some good critical praise, but not much else. Compare that to, say, The Blair Witch Project, which grossed roughly $240,000,000 at the box office, and you get a pretty good sense of the difference in scale. Granted, the Blair Witch thing was a real fluke, but it represents a level of opportunity that simply doesn't exist for the independent developer.

And while technology is making the lives of independent filmmakers easier with digital video cameras and off-the-shelf PCs running affordable editing software, the means to create a commercially viable video game are becoming more and more expensive and complex. Twenty-two years ago, David Crane essentially designed and developed Pitfall! all by himself. Eighteen years ago, Alexey Pajitnov did much the same with Tetris. These days, you might still call it Sid Meier's Whatever, and Will Wright gets lead designer credit on the next SimWhatever game, but both of these brilliant designers need a small army of people to execute their vision. The days of the video game artisan are long behind us, and every day the production of a video game becomes the collaborative effort of a larger and larger group of people. As such, the opportunities to realize a singular vision are becoming more and more scarce.

At this point you may be saying to yourself, "So what, you stupid hippy? If massive publishers like EA, Ubisoft, or Activision can produce great games, why do I care if some dudes in a garage can't get anyone to play their stupid Flash game?" Well, there are advantages to being an independent developer. When you're a publicly traded company, you're obliged to try to make as much money for your investors as you can while exposing them to a minimum amount of risk. This generally translates into lots of safe bets--games that are similar to previous successful games or games that carry some sort of marketable intellectual property. If you don't have as much financial accountability, you're free to try out something a little more radical. Games like Ikaruga and Serious Sam come to mind as perfect examples of the severe ideas that can come from a small group of people that, relatively speaking, have little to lose. These were also games that weren't developed to appeal to the broadest audience possible. They were built for a very specific audience, by people who have a great affection for that audience. Profitability wasn't a concern to the guy who created Counter-Strike--he just wanted to make an online shooter that would be fun for him and for his friends. These are the very reasons big publishers court independent developers in the first place--they're a great source for fresh ideas.

There are definitely small pockets of people fighting the good fight for the independents. The developers of Far Cry and Half-Life 2 are taking great pains to make their engines and their aftermarket development tools intuitive and easy to use, and the PC mod community represents grassroots game development at its finest. But still, I'm worried. I'm worried that the big publishers will continue buying up the little developers, until there are three companies making all of the games we play. I'm worried that the financial entry point for serious game development will become so ridiculously high, homegrown projects like Serious Sam will no longer be possible. People complain a lot about how all the games are the same these days, and if the businesses keep consolidating, I only see this problem getting worse. Big business and good games aren't mutually exclusive, but independent developers have been a wellspring of innovation and new ideas in the video game business for years, and I'm worried that the well's going to dry up.

| Tim Tracy Senior Producer, GameSpot Live |

A Studio of One's Own

GameSpot Live, as you and I know it, has been around for nearly four years now. We've been through our ups and downs and growing pains, and I've been along for the entire crazy ride. It wasn't until very recently that we saw the most dramatic change to the way we produce our video content--the construction of our new studio. Ryan Mac Donald, Dave Toole, and I have always dreamed about having one place to film everything we do, a dream that has finally come true. While we're still in the process of getting every last kink ironed out, for all intents and purposes, we're up and running. Perhaps you've noticed that our video reviews, previews and Let's GameSpot! have looked a little different lately. Honestly, I don't think our video content has ever looked better, but I'll let you, the viewers, be the judge over the coming months. I apologize in advance if this column is a little short, but you know what they say about a picture being worth a thousand words. So without further delay, I'd like to take you on a tour behind the scenes of the GameSpot Live back lot!

Well, folks, that's my baby, and boy am I proud of her. GameSpot Live certainly has come quite a long ways since we first started, and I can't wait to see what the future will bring. All I know for sure is that everything is going to look a whole heckuva lot better now!

| Tyler Winegarner Associate Producer, GameSpot Live |

Shouting Match

OK, so lately I've been spending a good deal of time playing Rainbow Six 3 for the Xbox. I'll be the first to admit that it took me a while to catch on to this one. I'm not usually a big fan of tactical shooters. I'm a much bigger fan of the speedy characters that can take a single rocket to the chest (if they're armored, at least) and come away laughing, if maybe limping a little. I like fast, fun action that keeps you coming for more, not sitting on a bench until the round is over. However, it's the headset that really roped me into this one. While it's often easier to key in your commands from the controller, that's just a lot less fun. Since my squad doesn't always move where I want them to when I point at the ground and tell them to go there, I was pretty shocked when I pointed to a door and idly muttered, "Open Flash and clear on Zulu," without thinking, and lo and behold, it worked! I was pretty shocked but instantly hooked.

OK, so I'm really happy with this feature, but I can't really claim to be satisfied. I want more, and by that, I mean, a lot more. I want to be able to take it a step further. I want to be able to command each member of my squad individually, either by painstakingly putting each member in his place or by having preset entry plans that are named, much like commands in a football game. I'd like to be able to have my own macros of my own entry patterns. Heck, it might be cool if they laughed at a joke I cracked. I want a game where I can get in a shouting match with a character in the game--real Gene Hackman or Al Pacino business is what I'm talking about here. I want to be entering commands with a headset that are as complicated as the ones I'm punching in on the controller. I want to play a game that requires the same intensity as Tommy Lee Jones in The Fugitive. If I get to be that much of a jerk, then that's just icing on the cake.

It just seems like the next logical step. While it's always been hard to figure out what the next innovation in controllers will be, I wouldn't mind one bit if the research tapered off there and developed in the direction of the microphone in front of your mouth. You want to talk about immersion? Imagine if you could command your troops in Full Spectrum Warrior by headset, and their squad morale was dependent upon your confidence in a firefight. This might be pushing it a bit, but what if Resident Evil Outbreak supported voice communication, and when players were turned into a zombie, their voice communication would be reinterpreted by the game, luring them instead of warning them? Or what if you could taunt your enemies out of hiding in a first-person shooter? The possibilities seem pretty limitless. Of course, I'm not the one hacking together the code to do it, so my job's pretty easy.

There seems to be a lot of uncertainty as to where to develop for the next generation. We've got our online, and that's great. Consoles are becoming a bigger part of the entertainment center, offering progressive scan, 5.1 Dolby Digital Surround, DVD players, the whole nine yards. There's the ever-present need of "bigger, badder, better" when it comes to crunching data and painting pretty pictures, and that's all well and good. But I think it's time to start talking about the future, quite literally, because between you and me, I don't think it's got anything to do with two screens.

| Jason Ocampo Associate PC Editor |

Where Have All the PC Games Gone?

I almost hate walking into a computer and video game store these days. It's almost depressing to see that, in most stores, the PC section has been pushed to the back corner. During the glory days, these places were almost exclusively PC software stores. But now, thanks to three major consoles (four if you count the Game Boy Advance) vying for the same amount of space, the PC section has shrunk to an alarming size.

It's not just that PC games take up less space, but the way the games are displayed is also disheartening. Most of them are older titles, stacked like books so you can only see their spines. When a game is spined out like that, there's nothing to catch your eye and make you want to examine it further. At least the new releases are faced out so you can see the front of their boxes, but there seems to be fewer and fewer new releases these days.

The sales data indicates this as well. The Entertainment Software Association announced this week that game sales topped $7 billion in 2003, a record high. However, most of that growth was due to console game sales. PC game sales fell $200 million from the year before. In other words, PC market share actually shrank from the previous year. That is really alarming news.

It's true that we've hit a dry spell of late; there just weren't that many major, A-list titles for the PC in 2003. And it surely did not help that Half-Life 2 and Doom 3, two of the most anticipated games ever, slipped to 2004. Yet even if they had made it out last year, it's doubtful that those two games alone could reverse the slide we've seen in PC gaming. There would have been a definite spike in sales and revenue, but it would not have changed the situation we're seeing now.

I think part of the problem is that the PC doesn't have a company dedicated to seeing the system flourish. Sony and Nintendo make sure there are plenty of games for their systems, because the more games they have, the more royalties they can collect. Third-party companies like Electronic Arts make PC games, but they make far more money on console games these days. Now, these third-party publishers aren't going to abandon PC games anytime soon because they still generate a substantial amount of revenue. But the fact is that they're going to invest more and more into the segment of the market that is growing, and that's consoles and not the PC.

There is one company out there that does have a vested interested in seeing PC gaming flourish, and that's the same company that benefits the most when people buy PCs: Microsoft. But over the past couple of years, the software giant has been investing more and more of its resources behind its own console, the Xbox.

Microsoft has let PC gaming slip under the radar of late, and this is a dangerous situation for the company. With Apple pushing hard to capture market share and Linux getting all the media attention, Microsoft has to realize that one reason gamers choose Windows over Mac or Linux is that Windows has all the games they want to play. Let PC gaming languish, and you eliminate a reason for a consumer to choose a PC over a Mac. Sure, the PC will always get major games like Half-Life 2 and The Sims 2, but the Mac will get those huge games as well. It's the large variety of games that the PC has and the Mac doesn't have that makes the PC attractive to gamers.

Microsoft has signaled that it recognizes this, and the company announced last year that it was focusing more effort to make Windows friendlier to gamers. But so far, this has amounted to a relatively lame game analyzer that scans your system and tells you what kind of games you can play. The company is also reportedly working to make Longhorn, the code name for the next generation of Windows, as game-friendly as a console. But Longhorn isn't scheduled to ship for another two to three years, which is an epoch in computing terms.

There should be alarms going off in Redmond over the state of the PC gaming industry. Unfortunately, with the recent departure of longtime games division chief Ed Fries, it's not clear what Microsoft's PC gaming strategy is right now. But what is clear is that Microsoft needs to invest more energy and resources into PC gaming now, because if it waits around for Longhorn, it may be too late.

| Alex Navarro Assistant Editor |

A Matter of Reputation

A couple of GameSpottings ago, I made a New Year's resolution. That resolution was to play fewer horrible games than I had the previous year. How many did I review the previous year? More than I'd care to comment on, really, so let's move on. In that very same GameSpotting, I also projected a date on which I would break said resolution: January 14, 2004. This was just a date that I picked completely at random, with no intended significance or premonitions of things to come. On January 14, 2004, not only did I break that resolution, I did so in spectacular fashion by reviewing the worst game ever reviewed on GameSpot. This rather spectacular coincidence would seem to only confirm something that I have suspected for quite some time now but have only recently been able to back up with solid evidence. You see, it is all too clear to me now that I am, in fact, destined to forever review crap.

I suppose this shouldn't come as any sort of a shock to me, as I'm no stranger to pain. Ever since my career in the game business began, I've been dealt one horrid mess of a game after another, no matter which company I work for. In fact, GameSpot isn't even the first company I've ever worked for where I broke the "bottom-of-the-barrel barrier," so to speak. Back when I worked as a freelancer for GameCenter, the old gaming site for our parent company, CNET, I slapped a game with the first 1 out of 10 in that site's history as well. Of course, they didn't use decimal points in their scoring system, but it was still a pretty big deal for them at the time. Now, keep in mind, it's not like all I review is crap--throughout my career, I've reviewed plenty of good, great, and superb games as well. On top of that, it's not like anyone else here at GameSpot has been absolved of reviewing their fair share of crap either--whether it be Greg, Jeff, either of our Ryans, Brad, Bob, or whoever, everyone's had to deal with their own terrible games. But, I suppose there is no denying that I do get more than the lion's share of the truly awful stuff, and as such, I can see I've gained something of a reputation for being the guy who reviews all the crap games.

I forget at exactly which stage of my GameSpot employment the reputation began to build, but over the last six months, I've seen an increasing number of forum posts, private messages, and e-mails come my way that generally express sympathy toward my having to review varying degrees of awful games. Some have suggested that perhaps Greg and Jeff are "out to get me" in some fashion or that I should be rewarded for my willingness to deal with the dregs of gaming by being allowed to review the next "AAA game," like Half-Life 2 or Halo 2 or something. Let me be the first to say that such insinuations and suggestions are entirely appreciated but, at the same time, entirely unnecessary.

I know that in various video pieces I've been involved with regarding bad games, I've made things out to seem as though I were some sort of tortured soul that needed to be pitied for having to review such trash. In case it wasn't obvious, these pieces were intended to be humorous, but it seems as though some people still think they have to feel sorry for me. Let me make one thing absolutely clear: My job is to play video games. Whether they are unmitigated trash or the best thing since sliced bread, it absolutely does not matter. I get paid to play games and write about them. This is not something to complain about in any regard. Sure, on any given day, I'd be far happier to be playing good games rather than bad games, but there is still a certain level of satisfaction from playing terrible games.

For starters, it really doubles your appreciation and affection for great games and the amount of time and effort it takes to make those games great. Furthermore, we provide a service to all of you by playing these horrid titles, writing our reviews, and posting media of them so you can read all about them, see them in action, and never, ever have to play them yourself--not to mention the silly fun that can be derived from producing video reviews for these monstrosities. Lastly, as I've said before, I've been doing this for a long time--since the age of 16, in fact--and I've come to terms with my preternatural tendency to be assigned bad games. I'm numb to their inherent awfulness--their powers are useless. Whether it's because I sincerely don't care anymore, or because over the years they have ravaged my soul of all manner of feeling, either way, they can't hurt me anymore, no matter how hard they try (and believe me, they try).

More than anything else, I simply wanted to use this column to express to everyone that they needn't worry about me, or my sanity. All the e-mails and forum posts and random conversations dedicated to expressing sympathy or pity for what I have to go through every time I review a terrible game, while appreciated, really aren't necessary. I love my job, and even though I don't necessarily love everything that comes along with it, that doesn't matter. My job is to help inform people about which games they should be buying and which ones they should be avoiding like a painful disease, and I can't very well do that if I don't review the diseaselike games, now can I? As for this reputation I've managed to acquire, so be it. If it is truly my destiny to be the guy who reviews everything that sucks, then I will take my destiny head-on. I'm here to inform, dammit, and I'll take whatever crap comes my way in the process.

| Adam Buchen Editorial Intern |

Making Sense of the HD Mess

In the past few years, one of the most visible changes in the world of consumer electronics has been the gradual acceptance and increasing accessibility of high-definition televisions. Furthermore, there has also been an increase in the number of different types of TVs available: LCD, plasma, video projectors, and DLP televisions have rapidly become popular in a landscape that had previously been dominated by traditional tube televisions and rear projection big screens. Don't get too caught up in the acronyms; the important thing to remember is that there are now a whole lot of different types of TVs out there, and a lot of them support HDTV.

High-definition TV is a significant revolution in the video world. It's television with a higher resolution; this means the picture has more lines and more pixels, which in turn provides a lot more sharpness and clarity. Furthermore, HDTV is a widescreen standard, more like a movie theater screen than the traditional TV picture, which is closer to square-shaped. All told, when you're viewing something in high-def, it looks much better and provides more of a cinematic experience.

To take advantage of high-def sets, however, you need a signal that is broadcast in HDTV. Most cable companies don't carry this signal yet, and while you can get HDTV via satellite, you'll still need a converter box, which will set you back upward of $500, and an antenna to view your local channels in HD. Right now, it's complex and largely unrewarding to buy a new set if you're after programming in high definition.

However, for a mere $179, you can purchase an Xbox, which is perfectly capable of outputting an HD signal! When Microsoft was first launching the console, the HD capability was rightfully one of its most touted features. The console represented a step forward in technology, something that would go great with that brand-new 50-inch plasma. It appears, however, that reality didn't end up quite as planned, given the rather meager selection of high-definition games on the system.

Sadly, very few of the Xbox games out there actually support true high definition. Perhaps even sadder is that almost no Microsoft-published games support it. A number of the games that do support it aren't very good to begin with. For instance, Enter the Matrix supports HDTV, but that just means you can see your dull, ugly textures and Nvidia logos at a higher resolution. I was genuinely excited about Soul Calibur II being in high-def, but when I loaded it up, it was not, in fact, in widescreen. Now that would be disappointing if you had just spent a few grand on a widescreen HDTV, wouldn't it?

I'll give Microsoft credit, however, as the Xbox is the only console to actually support high definition. The GameCube and PS2 support progressive scan, a mode that does indeed make the picture look better but does not actually increase the resolution. While almost every significant Xbox game at least supports this mode, it's more hit or miss with the other two systems. To compound this dilemma, there are some games that support the mode but have no documentation or indication whatsoever to let you know that. I have absolutely no idea why this is, either.

From a videophile's perspective, this generation of consoles has really been somewhat disappointing. It would have been nice to have a lot more of those games support the high resolution. Now before you start sending the angry e-mails, let me assure you that I believe gameplay is still the most important aspect of video games. But if the technology exists, why not take advantage of it? If you feel that today you honestly wouldn't mind a home console that displayed images in grayscale, then you may commence flaming.

There is still a little time left in this generation to salvage it to some extent. Microsoft, you have one really big release coming out this year, and I'll be extremely disappointed if it's not in HDTV. Sony, Nintendo, please at least try to get consistent information about progressive scan support on the back of the box, if nothing else. Also, even though you can't do HD, you can at least ensure that games have widescreen support.

Finally, I make this plea to any company who plans on releasing a next-generation console: Please include HD support! Believe it or not, some people actually care about this feature, and to just shrug it off so carelessly is to do a disservice to a lot of gamers.

As the home theater becomes more advanced, there is no reason that gaming systems shouldn't keep pace. Microsoft has proven that it's not necessarily that expensive to implement the technology, and by the next generation, an even larger number of people will have high-definition sets. It only makes sense to take advantage of this technology that makes games look a whole lot better.

| Nick Mendez GuestSpotter |

Walking the Line of Reality

"It's just a game." Isn't it crazy that to some people out there, those words can be downright painful to absorb? That they can cringe with the simple thought that the experience they are going through is merely a product of someone's creative mind, put together with a digital hammer and nails, millions of lines of code, and some paint-shopped artwork? They can refuse to realize that they aren't touching those walls or gripping that gun. They don't want to be told that the money they're earning is merely a value located on a Web server somewhere. And the single-most painful thought of all for them is that when you really look at it, in the end, all the work and time they pour into their games, no matter how entertaining, all just washes away. If an online game closes down, it can be the end of their very own virtual world, an abrupt and startling digital Armageddon.

Of course, the majority of us don't see things that way. We all play games, whether it be on our couches or sitting behind a computer, and obviously if you take the time to read editorial features about video games, such as this one, you enjoy playing games very much. But most people can take a moment to step away from that entertainment and continue the learning process that is real life. Games are an incredible form of entertainment, and I personally have no regrets regarding the hours I have spent playing video games. Games have caught on because they engage you in ways no other form of media or entertainment can.

One specific genre that seems to be catching on is the massively multiplayer online role-playing game. I'm sure that all of us have had some level of exposure to the likes of EverQuest, Asheron's Call, Dark Ages of Camelot, or Anarchy Online. Millions upon millions of dollars are taken in by this genre, and hundreds of thousands of gamers live these virtual lives every day. But at what point does society have to draw the line between life and a game? Taking a look at some of the original pioneers of the genre, one key feature expressed was always that you would experience a living and breathing world. However, if you read about the next MMORPG everyone is waiting to step into nowadays, that feature no longer even seems impressive. Is it really so commonplace to create virtual worlds that this process goes on primarily unnoticed? Keeping in mind that it's not really your feet walking through those worlds, is it really so difficult for some to distinguish these creations from the very world that we live in today?

You've all heard the stories of gamers becoming horribly addicted to games like EverQuest. Recently, the possibility of a gamer playing for so long without any recognition of the world around them, to the point where death can occur, has stopped seeming so far-fetched. Now, I'm not one to blame deaths or violence on games--no, I find that to be quite ridiculous. But I also cannot ignore personal experiences I've had with people that display an unhealthy attachment to certain games.

Recently, I went out and picked up the recent expansion pack for Anarchy Online. The game has great art direction, and I immediately started to enjoy myself. I progressed through the game, never taking it any more seriously than I take a game of Madden or a Rainbow Six match. But slowly, I engrossed myself more and more into the game and got involved with in-game organizations and the like. As I began to dig deeper, however, the reality really began to strike me. I vividly remember talking to several individuals who at the mere mention of this being "just a game" shockingly urged me to drop the subject and not say something like that around them again. At first many might only see this as the behavior of someone trying to immerse themselves in the game, something many MMORPG players tend to do. But as I thought about it further, I began to realize a lot more about this strange experience.

The genre has long scared away new players due to the huge amounts of time needed to be successful. Sometimes progressing your character through a game like this can seem more like work than entertainment. Very time consuming work at that. One of the key aspects is the social interaction between players, but many times you run into someone who brings a sense of anger and argument into the game. You can find yourself working out problems, making painful decisions, and putting in countless hours for "the good of the team." I suddenly found myself realizing that by bringing so much seriousness and work into a game, I was ignoring the very experience we play games for. If we play games for entertainment, and to get away from work, and the stressful lives we all live, why is it that countless people actually pay money to manage another, virtual life, which sucks hours out of one's day?

It's a true yet disturbing fact that some actually see these in-game characters as alternate lives to be lived on a schedule. In discussing this with other players I began to think if by immersing ourselves in a life where we cannot smell, touch, or truly experience anything, due to the confines of digital technology, are we denying what truly makes us human? Are these players that put countless hours into digital lives that can all be wiped away in a second, due to lack of funds or the closing of a server, missing out on the real life events passing them by? It was with those thoughts that I hit the cancel button on my account, for the first time not with dissatisfaction with the game but with a desire to remove myself from what I no longer view as a game but a social experiment. As the technology allows these games to become more and more immersive, is this experiment in creating worlds blurring the lines between reality and entertainment?

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation