Mapping out Call of Duty: Black Ops

Treyarch developers hit Call of Duty XP to explain the method behind the mayhem, show the maps that never made it into the game.

Who was there: David Vonderhaar (lead game designer), Dan Bunting (online director), Phillip Tasker (senior game designer), and Alex Conserva (lead software engineer).

What they talked about: While the majority of the Call of Duty XP attendees were busy shooting each other on various maps across multiple Call of Duty games, Activision held several panels for those looking for some behind-the-games insight. One panel focused on multiplayer, or more specifically, multiplayer maps.

Tasker recounted the experience of coming up with the Summit map--he and the rest of the panelists traveled the world for inspiration. He mentioned that it can take several months or up to a year to make one map. For Summit, they were still a year and a half away from shipping Call of Duty: Black Ops. Some mock-ups were displayed on the large screen to give fans an idea of what the layout used to look like. Textures aren't added until six months before the ship date and finally the polish phase is when they push to make it look as beautiful as possible.

As for the people who put the maps together, Tasker said, "Call of Duty level designers are three-part designers: one part artist, one part architect, and completely insane."

Even though maps don't always make it into the final game, there are times when the development team scratches an entire environment. A Cairo-themed area with temples and pyramids was ultimately cut from the game, but instead of losing out on all that work, the map location was moved to Cuba, and they were able to rework the original map to suit the new country.

Throughout the panel, the panelists would call on the audience to guess the map. One map, which fans immediately recognized as Nuketown, was not actually it. It was called Empty Nukes, and Bunting explained that it was a map that let the designers experiment with new ideas. These original ideas will generate other ideas and will eventually lead somewhere new.

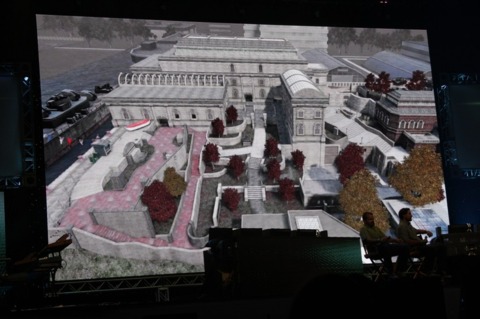

A map that looked similar to Castle was actually the War Museum, a clean, immaculate-looking shrine that was decorated with paintings, medals, and bronze statues. A video was shown to give the audience a tour of the map, which was ultimately never used.

Maps also undergo multiple name changes. Area 51 was changed so that they wouldn't get sued, but other changes were made for more trivial reasons. Some maps had boring names, and some names were changed because the letter they started with was the same as too many other maps.

The next part of the panel highlighted some excellent user-created art that they were legally allowed to display. The panelists joked that with the creator, they knew that there would be plenty of beautiful art along with all the horrible things that people come up with. They had to hire a full-time employee to monitor the creations.

During the Q&A portion of the panel, Tasker was asked by a member of the audience to talk about the design process flow when it came to creating the maps. He talked about how it all starts with paper and that there needs to be a concept. Working on paper helps give them ideas and work out the flow of the map. There are some rules to adhere to, even though Tasker pointed out that some were made to be broken. For example, when a player walks into an area, the exit should always be visible. Maps should also be designed in a way that players will eventually collide with one another. Part of the process is also to "play the hell out of the maps," said Tasker. The team gets together daily to see if it works and if it's fun.

Another question was asked regarding the development of the modes in the game, and Bunting described it as very similar to the map process, where they start with an idea and then the design team will spec it out. Engineers will build a quick and dirty prototype that allows the team to playtest the mode. Conserva added, "You'll know right away if you get something good or not."

Quote: "The point here is that ideas generate other ideas. Sometimes you'll have to let somebody not do what they're supposed to do because it leads you somewhere else."--Dan Bunting on playing with new ideas when it comes to designing maps.

Takeaway: A lot of time and research goes into a single map, and they don't always end up in the game or even in future DLC. However, it's not uncommon to take what has been created and work to change the environment to reflect an entirely different location. The process isn't easy, and it's time consuming, but it's possible.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation