INTRO:

Eador: Genesis is the brainchild of Russian developer Snowbird. Snowbird apparently has many ideas for its game, which it implemented mostly well. As a result, Eador: Genesis is an incredibly sophisticated turn-based strategy game, and even more surprisingly, one which does not rely on random number generators too much.

However, it has issues fulfilling its own promises. Up until this time of writing, the game still lacks any multiplayer mode, despite the promise of one. Its campaign mode is also an exercise in repetition.

Most importantly, it would appear that support for the game would all but dry up, what with its “re-mastered” version, Eador: Master of the Broken World, seemingly taking up most of the developer’s time these days.

PREMISE:

Eador: Genesis’s story is not a new one, but it is a rare one indeed.

The world which was Eador was once whole, with a formerly powerful and advanced civilization once ruling it. However, due to the ambitions of some who overreached their limits and the predations of otherworldly creatures (it is not certain which is more responsible), Eador was torn apart into pieces known as “shards”.

For the sake of simplicity, these shards should be considered as no more than just pieces of Eador which somehow still support life. There is some mystical hullabaloo which attempts to explain how they can still support life, that they appear as separate things in the Astral plane and such other fantastical things which would go over even the heads of veteran fantasy buffs.

Speaking of the Astral plane, this is a dimension where immortal beings reside, and which serves as a convenient setting for the campaign mode and the gameplay mechanisms which are associated with that.

Anyway, these beings bicker and fight each other for the possession of the shards, which grant them the power to continue existing and, of course, obtain more shards in the hope of remaking Eador again (in their own image).

The player is one such being. In the campaign, the player character had just started its reign from scratch, and must work to gather power before the extra-dimensional powers of Chaos overwhelms the remains of Eador.

Unfortunately, such a seemingly epic story (which the game’s sales pitch itself mentioned) is bogged down by a lot of repetition and boring presentation, which will be described (much) further later. Simply put, it takes backseat to the gameplay of Eador: Genesis.

MATCHES – OVERVIEW:

The match – which is a session in which the player competes with other players (A.I. or player-controlled) for victory and control of a map – is the core of any gameplay mode. The map concerned is none other than a “shard”, which is a cluster of adjacent provinces.

Each player typically starts in one corner of the map, the halfway point along any edge of the map, or somewhere in the centre of the map. Depending on the size of the map, the starting point permutations vary between these. The province which the player starts with is his/her/its stronghold, which the player must protect or lose the match.

Afterwards, each player takes his/her/its turn to make decisions on what to do. Decisions which build up provinces or the stronghold have immediate effects, as well as any decisions to recruit heroes or other units. However, the consequences of other decisions only come into being upon the player ending his/her/its turn. There will be more elaboration on specific decisions later.

These decisions should contribute towards the player’s control of the map, the building-up of resources, the improvement of heroes and their armies, and eventually the cornering of opponents. The player must successfully capture the strongholds of other players, a feat of which removes them from the map, while protecting his/her own.

Of course, all these are easier said than done. They may also seem “done-before” many times already, but there are nuances which make Eador: Genesis more special than the rest; these will be described later.

STRONGHOLD:

The first asset that the player starts with is the stronghold. The stronghold is actually the capital city of the player’s realm on the shard.

The facilities and enclaves which the player would build within the player’s stronghold determine the availability of means and resources with which the player would use to prosecute his/her war with.

Building up the stronghold is not a linear, single-direction path. There are many decisions with opportunity costs which the player must make, with the most important being the ones concerning which human units the player would like to be able to recruit and the magic spells which would be readily available for heroes to learn and keep in their spellbooks.

The stronghold also contains the amenities which heroes need to have their gear repaired, their party replenished and their spellbooks rearranged. However, having heroes spend turns to return to the stronghold is not a wise expenditure of their time; the player must build additional amenities elsewhere, but this is of course for another section within this review.

Perhaps the most important function of the stronghold is that it is the only place where new heroes can be recruited into the player’s service, or revived if they died (and the player decided to keep them instead of letting them rot). This is important to keep in mind when having to push against enemies and sacrificing heroes in battle to weaken tough enemies.

RESOURCES:

The stronghold may be the seat of the player’s power, but for it, and the player’s heroes, to be effective, the player must have the necessary commodity-based resources.

There are only two types of resources to consider: gold and gems. The ways in which these work are nothing new; similar examples have been seen in games such as Age of Wonders (and there are even older examples).

Gold is of course needed for the recruitment of units and heroes, construction of buildings, repairs of gear for heroes and for the resolution of side endeavours, among many other things.

Gems are Eador’s take on “mana” or “crystals” as seen in other turn-based fantasy strategy games. These are the most basic of materials needed for magic. Units with an affinity for magic (either innately or developed later) require gems as upkeep. Gems are also used to cover secondary costs in the construction of buildings. Certain gear pieces, especially very powerful ones with plenty of effects, demand gems for their purchase too.

The most important use of gems is in the casting of spells. Spells can turn the tide of battle very easily. Coincidentally, the most powerful of them consume considerable amounts of mana.

SPECIAL RESOURCES:

For lack of a better word, “special resources” would be the name of another tier of resources.

These resources are unlike gold and gems, because they are not expendable. They are found in only a few provinces, and are usually associated with specific terrain types. For example, redwood is only ever found in forests, whereas iron is always found in hills.

They may seem familiar to people who have played games in the Civilizations series. Yet, they do not behave as technology “enablers” or prerequisites like the special resources in the Civilization games.

Instead, they have two kinds of particular effects to gameplay.

The first is that they are counted as secondary resources for the construction of buildings and the recruitment of certain units. If the player does not have provinces with the necessary special resources, these endeavours can still be pursued, but they come with higher costs; this is explained away in-game as the premiums which the player must pay to get the resources.

The player must pay for each “unit” of special resources which he/she does not have. Furthermore, each time the player, or a competitor, does this, the prices of special resources increase. They may even increase to incredible levels, e.g. redwood becoming more expensive than mithril, which is usually more expensive.

However, if the player has managed to obtain the special resources later, all of the additional costs for other projects which need them are waived.

This effect is a lot more forgiving and perhaps more refreshing than the designs of special resources in other games.

The second is for purposes of turn-by-turn events. The presence of these special resources can result in special events which affect the province, and these events may require the player’s input. Usually, these events are desirable, such as the presence of black lotus allowing alchemists to create performance-enhancing potions. (Yes, the game’s writing does have a sense of humor.)

However, if the player has really bad luck, he/she may get a special event which threatens to remove a special resource from a province which has it. Conversely, the player may even obtain special events which can grant special resources unto a province which previously has nothing special.

Unfortunately, these are not the only luck-dependent gameplay designs in Eador: Genesis.

Some special resources are immediately revealed to the player (and any other players). This is the case for horse herds, which are always visible whenever they occur on any plain provinces (more on province terrains later).

The other special resources are not always visible. They may already be revealed, waiting for a player to capture their owning province. Even so, they may be revealed but are guarded by creatures who do not appreciate their ownership being taken away.

Then, there are special resources which are not revealed at all. The player can only guess which provinces have any special resources by looking at their terrain type, but this is not a reliable way. To better narrow down the player’s search, the player will need to have facilities in the stronghold which reveal the presence of special resources in provinces.

(Incidentally, the player will be building these facilities anyway, because they are prerequisites for many more advanced buildings.)

SHARDS – PROCEDURAL GENERATION & DATABASE:

Before going onto provinces, the gameplay designs for “shards” which they belong to will have to be described first.

“Shards” are the name which the game gives to its maps. Each “shard” is a collection of adjacent provinces.

These provinces have borders with no uniform shapes, though they are indeed clearly polygonal. Each province generally has five or more sides and has at least five neighbouring provinces, including uninhabitable ones such as mountains and bodies of water. Speaking of which, each province is also associated with a terrain type. Also, there are a few provinces which will be designated as the strongholds of players.

These features of shards are metaphorically written in stone; the data for these is apparently contained in a considerable database. The game draws from the database to generate shards for the campaign mode and one-off matches.

The other features of a shard and its provinces, however, are procedurally generated. These features will be mentioned later where relevant.

PROVINCES – IN GENERAL:

Capturing provinces and exploring them are the most important gameplay activity which the player would perform. This is because provinces are the main sources of opportunities to gain resources, units, hero gear and other assets to fuel the player’s progress to victory.

However, not all provinces are worth capturing. Recognizing which are not worth capturing can be a daunting lesson, but there are ways to know which are worth taking almost immediately, as will be described later.

As mentioned earlier, each “shard” is a collection of adjacent provinces . Each player already starts with one: the stronghold. The stronghold province tends to be quite well-explored already, and more importantly, it

has many locations (more on these later) already available for heroes to go to and clear them out for early-match loot and gear. The stronghold also has a relatively high number of locations (already available and still undiscovered) which are easy to clear.

Eventually, the player must take other provinces to expand. These other provinces may already have some locations revealed, or are relatively uncharted. The player repeats clearing locations at these other provinces to gain more means to prosecute his/her campaign.

More importantly, only non-stronghold provinces can have special resources; these will never appear at strongholds. In fact, it is more than likely the player’s expansion plans will be oriented around getting these; not having to pay extra for many things which need them is a good incentive.

The player will also need to develop these provinces, usually to improve their economic output or to turn them into resupply and forward bases for the player’s heroes. Provinces which are next to other player’s provinces can also be turned into observation points, though other players will be well aware of the player’s intentions.

PROVINCE - LOCATIONS:

The second-most important things which a non-stronghold province has after special resources are its locations. These are the player’s main source of income and other assets necessary for victory, though luck may be a factor because the distributions of locations are procedurally generated.

Most of these locations are practically monster lairs and brigand dens; they can be cleared out for loot and sometimes items for heroes. The type of the lair or den is generally of no tactical importance, except when quests are involved and these require clearing these kinds of locations.

Then, there are locations which actually have an impact on the province, negative or positive.

The detrimental ones are more than likely to be the target of the player’s ire earlier than other locations. These include the Altar of Death, which reduces population growth in the province and even harbours the risk of undead uprisings. Another example is the Thieves Guild, which reduces income in the province and causes more than a few undesirable events involving daring thefts.

The beneficial ones are more often than not guarded by defenders already, which need to be cleared before these locations can convey their benefits unto the province. They are worth the trouble though, because they convey benefits which the player can be hard-pressed to replicate using construction projects in the stronghold.

For example, there is the Sanctuary, a shrine of sorts which improve the happiness of the province. Happiness-increasing bonuses are desirable, but the stronghold buildings which confer them are very expensive, so having locations take up the slack is a cost-effective alternative.

There are also locations which allow the player to recruit units which the player cannot obtain from the stronghold (which is mainly human-oriented, for reasons which will be described in-game). However, many of these locations also come with their own risks.

For example, harpy nests allow the player to recruit harpies, but the presence of the harpy nest also means that the province and its neighbours are at risk of harpy raids, which can be devastating. Another example is the troll lair, which is as bad as it sounds. In contrast, the Fairy Tree is benign.

Interestingly, the player can choose to attack them and plunder them, forever preventing the player from using them to recruit units in return for short-term gain.

An important detail about any location which has yet to be cleared is its defenders. The game will not fully describe the number and composition of defenders at a location. Instead, it merely uses a phrase which broadly describes the defenders.

It will take a while for a player to determine which phrase results in which kinds of defenders. For example, “Barbarian” defenders will obviously have Barbarians in them, but they usually have Shamans too and for more challenging “Barbarian” groups, there are Thugs as well. Only an experienced player would be able to expect what to fight from the phrase alone.

This can seem to make the learning curve of Eador steeper than it should be, however.

An interesting risk-versus-reward mechanism lies in the gameplay element of defenders. Generally, more powerful defenders yield better loot when they are defeated. This is not just additional gems and gold; very powerful defenders can yield powerful items.

(Of course, ironically, the player will need to already have a kitted-out, high-level Hero to clear them out with, but the items might be handy for other heroes.)

PROVINCE – EXPLORATION:

The treasures and dangers which a province has are not completely revealed to the player. Many provinces in any shard are broadly unexplored.

If they are already populated by natives (which often make up the defenders of the province), they are usually already partially explored. However, if the province is blighted by undead or demons, it is practically wild and unknown, carrying plenty of risks (as to be expected of lands which were overrun by undead or demons).

The act of exploring a province can only be performed by heroes and heroes only. This means that the player must balance the exploration of provinces against the capture of more provinces (which can only be performed by heroes too).

Exploring a province may reveal locations. The types of locations which the player can expect depend on the nature of native defenders (or source of blight) of the province.

For example, if the province was originally overrun by undead (it would be called “dead lands”, in this case), the player can expect a lot of locations which are inhabited by undead and more than likely an Altar of Death.

The types of locations also depend on the terrain type of the province. For example, forested provinces tend to have magical thickets, which generally yield gems when cleared.

Exploring a province and revealing a location requires the transition of a turn; the player cannot make decisions on such occurrences during his/her actual turn. Fortunately, unlike other decisions that are resolved during the resolution of a turn, the decision of attacking a location can be delayed. Therefore, the player can “stock up” on a bunch of locations to be cleared later, either by a more capable hero (and army) or by a nascent hero who has been recruited later (so that he can build himself up from the spoils).

Sometimes, exploration yields not locations, but one-off events. Most of these resolve themselves, such as the hero finding a cache of treasure (which generally has a good outcome). Some others require the player to make a decision, such as the discovery of a Halfling community (which the player has several choices of dealing with – including outright plundering it).

Every time a “shard” map is procedurally generated by a game, varying percentages of explored lands are applied to the provinces in it. Such percentages are usually associated with the original inhabitants of the province, if any. For example, free settlements (which are populated and guarded by humans) usually are already explored by around 30% or more.

Speaking of percentages of explored lands, these act as progress meters of sorts to how much of a province has been revealed. Locations are seeded at certain percentages; to have a location revealed, the percentage must reach its associated value.

This system would seem to be quite understandable, if not for an issue over how the game applies the exploration rating of heroes.

To elaborate, each exploring hero can only ever reveal one location over a turn. Even if his exploration rating is far higher than the remaining percentage points needed to reveal the next location, the percentage of revelation which the province gets over a turn is resolved at the percentage associated with that next location. In other words, any excess exploration rating that the hero has is wasted.

Fortunately, the player can mitigate this by having more than one hero explore a province; the game will efficiently apply their exploration ratings.

However, this reveals another problem. Only the hero who revealed the next location is allowed to interact with it during the end of the turn; the other hero, or heroes, can only do something about the location in the course of the next turn.

As a province becomes more revealed, it becomes harder to explore the remaining areas in it. This is represented by a penalty on the exploration rating which is applied on the exploring hero at the end of a turn. Therefore, unless the player is sure that the province has plenty more locations, exploring the remainder of a province becomes an increasingly inefficient way to spend turns with.

Indeed, inexperienced players would learn the hard way that they have been wasting turns on exploring provinces which no longer have any locations when they could have been capturing more provinces instead. Sure, fully exploring a province grants a bonus to the province’s gold income, but this bonus is just too small to be worth the trouble.

PROVINCE - TERRAIN:

There are several types of terrain which a province is made of, though only four of these are habitable.

The most convenient of these terrain types is plains (i.e. the province is mostly made of fields). Plains are easy to explore, thus allowing heroes to use their exploration ratings to the fullest, at least until the penalties for having mostly explored the province are applied. Plains are also the only terrain where horse herds can be found.

Next, there are hills. Hills are a bit more difficult to explore than plains; this difference is applied via penalties on heroes’ exploration ratings. Nevertheless, the player may want to explore hills anyway, because no fewer than three types of special resources occur in hills. Furthermore, hills also hinder movement across the shard, so they can get in the way of retreats.

After that, there are forests, which are more difficult to explore and move through than hills. Forests, typically, are where redwood groves can be found. It is also where thickets of dionite can be found; dionite is practically magical tree amber. In terms of economics, forests tend to exchange income with population growth.

Finally, the last habitable type of terrain is swamp, amusingly enough. Swampy provinces are notoriously difficult to explore and move through, even more so than hills and forests. They also produce battlefields which are terrifically difficult to fight on; there will be more elaboration on battlefield terrain later. Moreover, swampy provinces tend to have poor income as well as lousy population growth.

Hills, forests and swamps impede movement, both on the world map (which shows the provinces on the map) and on the battlefield; the latter case will be described later. On the world map, only heroes with skill in navigating these difficult terrains can have their parties moving through them without being halted.

(Even if all units within a party have battlefield knowledge of specific terrain types, they cannot move through the world map without suffering penalties. The hero of that party must have the necessary skill, not passive buffs.)

The movement penalties of hills, forests and swamps can be mitigated by building stables on the provinces with these terrain types. Although this comes with considerable opportunity costs (e.g. having a stable take up a building slot in a province), having heroes move through provinces quickly can be strategically important.

PROVINCE GUARDS:

Heroes and their parties (if any) can defend provinces simply by staying at them, but such use of heroes is often a waste. However, the player cannot just leave provinces undefended; other players can easily capture them, and even random events can result in these provinces being lost.

To prevent this from happening, the player can hire guards to defend the province with. Some options for guards are always available as long as the player has the money to hire and upkeep them with. Some others are rare, and can only be hired if the player has the (often sorcerous) contract to summon them with.

Guards are actually bands of units which are out of the player’s control; the A.I. always takes over the control of guards. In exchange for this lack of control, guards, if each of their member’s capabilities and costs of upkeep are considered, are a more practical and economically efficient way to protect provinces with.

These guards will take the brunt of any uprisings or invasions if the player does not have a hero in the province to do so instead. They can take casualties though, which will take a few turns to be rectified. Successive invasions can overwhelm almost any kind of guard, except perhaps the most devastatingly powerful with upkeep costs in the triple digits.

Speaking of these devastatingly powerful guards, they can be a pain-in-the-ass to defeat. The player will notice that other players will start using these late into the campaign, often in order to protect their strongholds.

For example, the Forest Druids guard is one of the rarest guards, only made available through very rare contracts. They are terrifically troublesome, having a couple of clerics who can spam long-range heals and sprites which can accelerate otherwise lumbering but hard-hitting treants.

PROVINCE – ORIGINAL INHABITANTS:

Incidentally, all provinces already have their own guards, namely their original inhabitants. The type of original defenders appears to be randomly determined when a shard is generated. However, there are several types of original defenders which are associated with certain terrain types. For example, druids are often found inhabiting and defending forests and giants are almost always found guarding hilly provinces.

The strength and versatility of the defenders depend on the distance of a province from a stronghold (any player’s stronghold). The ones which are closer to a stronghold have much weaker inhabitants, which make them easier to conquer. The provinces which are four or more provinces further are much nastier.

Most of these original inhabitants have to be defeated in order to capture the province. However, if the player has a diplomatic hero, the player can attempt to work out a deal to have the original defenders be the province’s first guard (again) after taking over the province bloodlessly.

This is not practical for provinces which are close to strongholds, but the player may want to do so anyway because it can cement an alliance with non-human races, which bring their own small but unique set of buildings, unit and guard for the player to use.

It is worth noting here that humans make up the bulk of inhabitants on any shard. Even if the player has cleared a province which was once overrun by undead or demons, humans are the ones who settle in.

Incidentally, humans are also the easiest province inhabitants to defeat. This is especially the case for Free Settlements, which have mainly militia-level human units. An astute player may notice that there tends to be a string of human-inhabited provinces which connect one stronghold to another.

PROVINCES – HAPPINESS & UNREST:

Each province has its own happiness rating, which depicts the “mood” of its population (the game has a peculiar choice of words).

It is generally in the player’s interest to keep the happiness ratings of provinces high. A high rating boosts population growth, and also increases the chances of good random events happening.

However, this is easier said than done due to the occurrence of other random events which simply give the player trouble; there will be more elaboration on this later.

Unlike most civilization-building games, which inspired the creation of Eador: Genesis, the game does not have the happiness rating acting as a modifier of the probability of uprisings. Instead, uprisings are events which happen with certainty, as can be seen from a meter which measures unrest in a province. Once this meter completely fills up, a revolt will happen for certain.

The severity of revolts depends on past revolts in that province and how far the province is from any stronghold. Past revolts ensure that subsequent ones are worse. Mortals being mortals, they may forget past transgressions, given enough time of not reminding them that their ruler is awful.

Incidentally, provinces which are inhabited by non-humans have nastier revolts. This is because non-human troops are generally better than their human counterparts (this will be elaborated later), and they often have more non-human allies too.

PROVINCE BUILDINGS:

Buildings can be constructed in provinces to improve their utility. Some buildings function as amenities in the stronghold do, so they are plenty convenient to have in a province which the player has marked for location-clearing. Others mainly improve the province’s statistics.

However, province buildings are vulnerable to random events which damage them - random earthquakes in particular. In fact, certain buildings are prerequisites for certain undesirable events, such as thieves breaking into storehouses to steal a large amount of gold and fiery mishaps which burn down sawmills.

Any province usually can have only up to three buildings. However, there are random events which may allow the player to have up to four, if the player makes a decision which creates an additional building.

However, the same random events can result in one slot out of the three being occupied by buildings which the player does not want. This can lead to complications in the player’s plans for the province.

It should be noted here that the player is not reimbursed when he/she destroys a province building to make way for another. Furthermore, the player can only build one province building each turn, at least initially.

HEROES - OVERVIEW:

Heroes are undoubtedly the second-most important assets of any player, after the vital stronghold. They are the ones who do most of the work for the player, from exploring provinces to making the first stage of expansions right up to waging war against other players.

(Amusingly, a character in Eador’s story has a less-than-kind description of “heroes”, whom he describes as people who are particularly susceptible to the suggestions of beings of a higher order – which include the player, of course.)

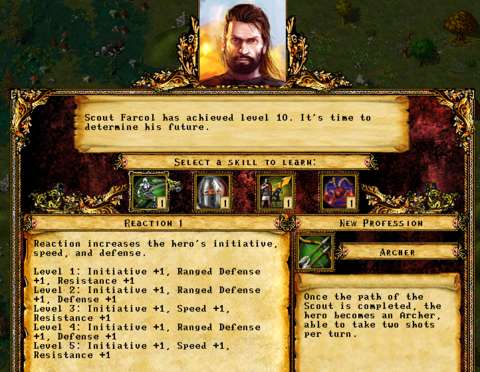

There are four types of heroes (all of whom are male): one who starts out melee-oriented, one who starts out with archery and exploration skills, one which is oriented around an effective army and one which is oriented around magic. Each starts with his own basic career: Warrior, Scout, Commander and Wizard, respectively.

The first Hero which the player recruits is the cheapest. Subsequent heroes are more expensive to recruit, and subsequent heroes of the same type are even more expensive. Therefore, the player should make his/her first choice – though this choice is easy to make, as will be elaborated later.

When heroes gain enough levels, they can change their careers to something else: either to specialize in what they already know, or to dabble in what other heroes do.

Which choice to make is easy to figure out, though – and not for the betterment of the game, as will be described later.

HERO EXPERIENCE & LEVELS:

As to be expected of a game system which uses the archetypal unit known as a “hero”, heroes gain experience in order to increase in levels, which in turn make them more powerful and versatile.

Interestingly, heroes can obtain experience from just about anything which they do, except for moving from province to province. The main way for a hero to gain experience is to engage in battle, as well as score kills during that. Heroes – and their party members - also gain additional experience from winning battles.

Heroes also gain experience from exploring provinces, but compared to other actions, this is the least efficient way to spend a turn accumulating experience for heroes. Nevertheless, the player may have to resort to exploring provinces to increase the experience of fledgling heroes if there are few locations which are weak enough for them to clear.

Nevertheless, the many ways with which a hero can gain experience does make Eador feel a bit different from many other fantasy strategy games which use Heroes in their gameplay.

The experience thresholds for gaining levels increase as a hero’s level increase, which is of course expectable.

Whenever a hero gains a level, he gains an increase to one of his statistics. Such an increase is taken from a library of increases; this library has several rungs, each associated with a certain range of hero levels and hero classes. For example, in the rung of increases for Warrior heroes of level 1 to 5, there is only one increase for the hero’s Magic rating, whereas the rung for Wizard heroes of the same level range has up to three.

A hero can only gain a type of statistical increase for a limited number of times, depending on his class and specialization (more on specialization later). For example, a Warrior which has specialized in melee combat can only take up to three increases in his Magic rating. In contrast, the Wizard can take a lot more.

This system of increases make certain that each hero would be slightly different from the last one even if the player has used the same development plan for both of them. However, they practically become the same when they reach the maximum level of 30.

Amusingly, heroes can still gain experience after they reach the maximum level. Of course, these experience points are completely wasted.

GAINING SKILLS:

The most important benefit of gaining a level is the opportunity for the Hero to pick up a new skill or improving existing ones. Skills typically confer benefits which improve the Hero’s statistic or impart special properties to their attacks, among other things such as a few skills which allow the use of special abilities.

For the Warrior and Wizard heroes, these skills are mostly only useful during battle. For the Scout, some of his skills make him far better at moving from province to province and exploring provinces, easily making the Scout the most versatile hero of the three.

For the Commander, his abilities improve the capabilities of units under his command, as well as make them cheaper to maintain and easier to move about on the shard. He is a lucrative tertiary choice for a hero if the player believes that he/she can have early-match access to non-human troops.

Speaking of choices of heroes, it is a rare player indeed who will not consider recruiting the Scout first. If the other heroes had more non-battle-related skills, they could have been a more viable alternative to the Scout when picking the first Hero.

Furthermore, the Commander is just not strong enough to help a bunch of rookie units survive the first few battles which they get into. He becomes more worthwhile only after he has gained some skills which considerably improve his units.

Interestingly, the benefits of certain skills cannot be replicated by heroes’ gear. For example, the Wizard’s skills which increase the number of spells which he can use are never replicable by any magic item, no matter how stupendously arcane it is.

However, some of the more mundane benefits of skills can be replicated by items. For example, there are plenty of gear which increase hitpoints, making the benefits of the Warrior’s Endurance skill a bit redundant (though there can never be such a thing as enough hitpoints of course).

Unfortunately, the otherwise entertaining and engaging system of Hero skills has a very frustrating caveat. When a hero gains a level, he has only three choices of skills to learn or improve. This can be an issue for players who insist on following build strategies, especially when the Heroes reach level 10, when they have to pick a specialization.

PARTY SLOTS:

Every hero can bring along some other units with him when he goes adventuring or on the warpath. He will be hard-pressed to do either on his own if he does not (but some hero builds are practically one-man armies; this will be elaborated later).

Initially, a fledgling hero can only take a handful of units with him. However, as he gains levels, he gains increases to his “Command” rating; this is the statistic which determines the number of unit slots which he can have to support the presence of units in the party.

Obviously, the Commander has the most unit slots compared to other Heroes of the same level. This is especially so for the Commander who later picks a specialization which furthers his original role. The Wizard and Scout have the least slots, unless they pick a specialization which turns them into a Commander-hybrid.

The party slots for the heroes’ followers are also tiered into ranks, to match the ranks of units. This design limitation has been deliberately included to prevent the player from recruiting higher-ranked units to support low-level heroes, which is a wise design decision.

HERO SPECIALIZATION:

Upon reaching level 10, the Hero must take a specialization – decided by the player, of course.

This “specialization” is depicted as advanced careers which the hero can take; each choice is mutually exclusive from the rest.

The main benefit of these advanced careers is the opportunity to either obtain the highest levels of skills which the Hero already has, or to obtain skills which are usually the purview of the other heroes, which improves their versatility.

The secondary benefit is a bonus to their statistics or an additional ability. For example, Warriors who take up the path of the Dark Knight (which turns them into a Wizard/Warrior hybrid) gain the ability to regain hitpoints from killing enemies. Another more extreme example is the Adventurer, an advanced career for the Scout which gives him the ability to use any gear piece without career-based restrictions.

Considering the benefits which specializations bring, the player is encouraged to focus on building up Heroes quickly.

However, there is a problem with specialization. The problem is that the decision to specialize is represented by skill options. The skill options may not be of the ones which the player would like to take for the Hero when he is level 10. The player has no choice but to take them anyway if he/she wants certain specializations, because specialization is a weightier decision than skill choices.

Still, being shoe-horned into taking skills which the player does not want the Hero to have yet can be annoying.

ON CERTAIN HERO BUILDS:

As hinted at several times already, a wise player would eventually notice that certain hero builds have far more raw power than the rest.

To be specific, these hero builds have the heroes picking specializations which augment what they are good at already. This comes at the opportunity cost of better versatility of course, but the player can use the raw power of the hero to bulldoze through locations in order to obtain money and opportunities to appropriate gear pieces which compensate for these drawbacks.

For example, the Warrior can take up the career of the Berserker, forgoing the others for the ability to go berserk. Considering that Berserk is a status which grants the affected person the ability to ignore the debilitating effects of wounds in addition to gaining bonus damage, this is a splendid boost (assuming that the player can somehow get the hero to be injured enough to go berserk.

Coupled with the opportunity to gain abilities such as “Charge” (which grants bonus damage according to the distance that the hero has used) and the army-wiping Round Attack, it may be hard to consider alternative careers to the Berserker. After all, if the player finds him lacking in some aspect, some special gear pieces can compensate for that.

In fact, with enough powerful gear, the ascended Warrior can practically go it alone and decimate entire armies. Only very powerful guards and cults (which are a type of defenders for locations) can stop such monstrous individuals.

Another example is the Archmage, which is the third phase of the Wizard’s career should he chooses to further his magical capabilities instead of diversifying. The Archmage gains the ability to cast two spells per round instead of just one; this alone makes the Archmage, and his earlier form, the Mage, too good to overlook. He will be a bit slow when moving across a shard, but few things can defeat an Archmage who is equipped with powerful spells (and he can have many of these).

It may be simply this reviewer’s opinion, but these builds are so powerful that they eclipse the others.

HERO GEAR:

Heroes are the only units who can be outfitted with items. Items are typically obtained as loot from winning battles or finding treasures, but they can also be bought at shops (though usually for high prices).

Specific hero classes are restricted to the use of certain items, such as wands being mainly the purview of Wizards and Bows the main weapons of Scouts. However, the Warrior is notable for being able to use all types of melee weapons, including heavy ones such as most axes and hammers.

The hero with the most freedom in using gear is the Adventurer, which is an advanced version of the Scout. This particular class can be powerful if the player has a plethora of items for him to use, but getting them is quite tricky and comes at the opportunity cost of developing a hero with exceptionally powerful ranged capabilities.

Certain types of gear are usable by any hero. These include all rings and other kinds of jewellery, and non-jewellery gear which has been classified as “common”.

Over prolonged use, usually in battle, the gear which a hero uses would eventually degrade; the only exceptions are jewellery, which are virtually indestructible (oddly enough).

Gear tends to break during battle, after which it becomes useless because its benefits (and side effects) are no longer being conferred. This can be particularly worrisome, if the player had been counting on the benefits of a piece of gear for winning a battle.

For example, a Warrior and his advanced melee-variants are terrifically devastating against poison-using enemies if he is using an item which grants him immunity to poison, such as the Phoenix Cloak. However, if this item breaks during a prolonged battle, the hero is in trouble.

Interestingly, as long as the durability of the gear is not zero, i.e. it has yet to be broken, it works at 100% efficiency. Perhaps this is so for simplicity’s sake.

Gear which has been damaged can be repaired; this can either be costly or conveniently cheap. Which case it is depends on the durability rating of the gear, because the cost of repairing the gear depends on the percentage of durability which has been lost.

This means that gear such as a fancy magical rapier, which has a low durability rating, is much more expensive to repair after its use in a battle compared to a similarly magical heavy weapon which has a very high durability rating.

As to be expected of a game with heroes and hero inventory systems, items also have varying classes of rarity. This is actually just a cosmetic label, but it gives the player a good idea of how powerful the item is, as well as its availability.

Particularly rare items do not just confer statistical boosts: they may have effects which are completely unique to themselves. This is the case for most Legendary-class gear. For example, there is the Banner of Unity, a Commander-only item which removes any penalties from having antagonistic units within the same party.

TREASURY & STRONGHOLD SHOPS:

The treasury – which is also the armory - is the screen where the player can see the spare items – or yet unusable ones – for Heroes. The player can only store a few dozen spare items, though it is rare that the player would run out of space.

The player can also access the shops in the stronghold from this screen. Shops in the strongholds are building options which are intended to provide the player with opportunities to kit out Heroes without having to visit shops in other provinces.\

However, in practice, the shops come with opportunity costs which are just too high. The resources which went into building them could have gone into something else, and the items which the shops sell can be found as loot, if the player is lucky.

SHOPS:

A special type of province location is the shop, which in turn has several variants. At first glance, they work a lot like stronghold shops. However, the differences can be seen after a bit more examination.

The shops generally offer much better goods than those in the stronghold shops. However, they are a lot more expensive to procure, even for goods which may appear in stronghold shops. Nevertheless, this increased premium might be worth the price, if only to obtain a rare item which rarely, if ever, appears in stronghold shops.

These privately owned shops might also offer one-off jobs for the hero who visited it – and only to that hero. Another hero cannot complete the same quest, though they may still be able to help in certain ways, such as giving an item which the hero needs to complete a quest (such as if it involves eggs or scrolls).

The shops, being locations too, can be attacked in order to rob them of their goods. However, shops tend to have considerable defences.

Successfully robbing a shop also prevents the player and anyone else from ever browsing its goods again. On the other hand, this is not a terrible consequence because shops do not appear to restock their goods, at least not after many, many turns.

Yet, there is a disincentive to hit shops. If the player successfully robs a shop, not all of its goods are given to the player; this is explained away in-game as some of the goods being destroyed or spirited away during battle. Even the goods which the player would get are damaged.

A certain type of shop, usually the sorcery store with gargoyle guards, happens to offer the aforementioned gargoyles for recruitment. They are costly troops, however.

UNITS - OVERVIEW:

Heroes are practically party leaders; they can bring along followers, who are recruited at strongholds or provinces with outposts (and their upgrades).

Their main purpose is to help their leader in battle. Very few units have abilities which work outside battle, except for certain healer units, which can accelerate the turn-by-turn healing of units. Speaking of abilities, the player is likely to recruit units for their abilities; units which start as vanilla grunts are rarely worth the cost.

As the units engage in and survive battles, they gain experience and become more powerful. They may even gain new abilities which make them more valuable. However, units which are killed and are still dead by the end of any battle are lost forever. This can be devastating if the player has been counting on a unit as a lynchpin.

Units generally require gold to be recruited. Some units, especially more exotic ones, require gems too. Most units also require special resources.

The costs continue after recruitment too. Most units require some gold as maintenance costs per turn, and some units require gems too. Undead and demons require solely gems for maintenance.

Failure to have the golds and gems necessary to maintain units results in the units losing morale and being unable to heal from wounds over time. Although this is not as bad as open rebellion, it is still terrifically debilitating. Therefore, it is in the player’s interest to keep reserves of gold and gems to prevent such an occurrence.

Every unit has a passage of description which imparts bits on the lore of the unit. Some are simple, such as the descriptions for low-level human units. However, the descriptions for more exotic unis describe the glorious past of Eador before it exploded into shards.

UNIT EXPERIENCE:

As mentioned earlier, units can gain experience from participating in battles. Unlike heroes, they do not have many other ways to obtain experience aside from participating in battles.

The experience thresholds for units are a lot lower than those for heroes, at least initially. Eventually, after a couple of levels or so, the thresholds become so high such that they require much more experience just to progress in the teen levels.

Nevertheless, it is in the player’s interest to keep units alive as long as possible, because they can obtain special abilities after obtaining a few levels. Even the lowliest of units, the human militiaman, can have abilities which make them more versatile and powerful than his formerly rookie self. For example, the militiaman can gain the ability to run, which makes him more capable at intercepting incoming enemies.

There are a few problems with the experience system for units, unfortunately.

The first of these is the same one which afflicts the Heroes: the advances which they can take are randomly picked from a selection of options and given to the player to as a very limited list of choices.

The second concerns the construction of buildings which grant bonus experience to units which have just been recruited. Units generally start as rookies, but these structures grant them bonus experience right at recruitment.

For the case of the bonus experience outright granting these “rookies” level advances, these units are given advances in relatively mundane statistics, instead of getting advances which grant them special abilities.

MEDALS:

At first glance, it would appear that heroes are generally more effective than non-hero troops due to their use of gear. However, troops can be tricked out with medals.

Medals are special permanent bonuses to the recipients’ statistics. To qualify for medals, a unit needs to gain enough experience to gain a level from a battle, as well as perform certain deeds during that battle. The requirements are considerable, but medals can grant considerable power to a unit.

For example, a unit which has scored many ranged hits at long range in a battle is likely to not only be given a level afterwards, but also the opportunity to receive a medal for archery. This medal increases its damage and range.

The choice to award medals is not automatically made though. The player makes the decision, which is just as well because there is the trade-off that medals actually increase the maintenance costs of the recipients.

“MORAL” ALIGNMENTS:

As mentioned earlier, heroes are weak-minded mortals who are practically vessels for the player’s will. However, other units are a bit more wilful; this is represented by their moral alignment. The moral alignments of the members of a party determine whether the modifier on the morale statistic which is applied to the entire party (except the hero) is a bonus or a penalty.

Some units, which are usually low-ranking human ones, have neutral moral alignment. They have no issues working with units of other alignments, and vice versa. The result is that there is an insignificant morale modifier for the party, which in turn makes such party combinations more versatile than most.

Other units with less ambivalent alignments have greater effect on party morale. If the player can include various units which have alignments on the same side of the morality scale within the same party, the party gains a considerable morale boost.

However, including units of starkly different alignments obviously results in morale disaster. This animosity obviously makes such party combinations rather undesirable. On the other hand, such party combinations have incredible versatility in battle, which might compensate for the morale risks.

The problem with moral alignments, however, is that there is no clear measure for these alignments beyond verbose and melodramatic phrases. For example, the player can only make a subjective observation that being “unscrupulous” is less “evil” than being “evil incarnate”.

PLAYER MORAL ALIGNMENT:

The player’s decisions in certain events determine the player’s own “moral” alignment. Generally, making a beneficent decision pushes the player towards the “good” side, whereas a cruel or nonchalant decision pushes him/her towards “evil”.

This will be considered in determining the morale of a party and when dealing with certain non-human races, so this is not just a cosmetic feature.

If the player wants to stay on one side of the “moral” scale, he/she will need to consistently make the associated decisions, because the player’s alignment will eventually return to neutral over time. This is explained in-game as a consequence of mortals’ short memories.

The player’s decisions during a war for a shard are also considered in the campaign mode. Certain other characters will not have kind regard for the player if he/she is of a particular alignment which they disdain.

UNIT STATISTICS:

All units, including heroes, have a set of statistics which generally come into play during battle. These statistics generally have simple names, though a few may still be a bit vaguely named.

For example, there are the numbers for “Attack” and “Ranged Attack”. From their icons, the player should be able to deduce that “Attack” is for melee attacks, whereas “Ranged Attack” should be obvious.

Otherwise, figuring what most these statistics do should be easy: they are mainly magnitudes of the effects of the actions which a unit can make. For example, both “attack” statistics are the average damage which a unit can do.

Some other statistics have more nuances. The simplest example of these is “Resistance”, which does not only reduce incoming magical damage, but is also a factor when determining whether de-buffs can be applied on a unit or not.

Statistics with more nuances will be described later in their own sections.

LUCK & STATISTICS:

Many games with turn-based battles utilize luck as a particularly significant factor. Pleasantly, for players who are averse to luck in gameplay, this is not so in the battles in Eador: Genesis – at least not as much.

There are no chance-to-hit rolls or probability percentages for a de-buff to be applied on a target, among other fickle gameplay mechanisms. This may well please players who want planning and tactical acumen to be the main factors of success. An astute and experienced player may well be able to know the outcome at the first turn just from the lay of the land and the capabilities of the combatants.

Unfortunately, there still has to be a small measure of luck in battles. This comes in the form of the damage which units can inflict with their regular attacks. Their “Attack” and “Ranged Attack” ratings actually show the average damage which they can make; there is still a 10% variance, the effect of which is especially apparent for units with high damage output.

This in turn inserts uncertainty into battles which involve very powerful units. The variance can result in very powerful but badly wounded units still having a couple of hitpoint lefts for their next turn, which means that they can still perform one more attack. Even though they may suffer penalties to their damage output (more on this later), their attacks would still be considerably powerful and might just turn the tide – possibly to the player’s chagrin.

STAMINA & WOUND EFFECTS:

Most games with turn-based battles treat units as having 100% performance regardless of how long they had been in battle and how injured they are. This is not the case for Eador: Genesis, which makes it rather refreshing compared to other games in the same genre.

Almost every unit has a stamina rating; this statistic diminishes as the unit performs most actions. To cite some examples, merely moving across familiar terrain does not cost stamina, but making an attack does. Making an attack after moving across terrain consumes stamina too, but at twice the amount.

If stamina gets below 5, it suffers penalties to its other statistics, including movement range (which is important). In fact, each point below 4 increases the penalties. If a unit’s stamina hits zero, it can do nothing and both of its defence statistics are set to zero while it is forced to rest.

In other words, the player can resort to tactics which drain stamina from enemies to handle targets which are very tough.

Every unit has a hit point rating, obviously. What is not obvious though is that every hit point rating has thresholds below 50% of itself. If a unit is rendered literally half-dead, it starts to suffer penalties to its attack ratings. Although these penalties are not as bad as the penalties for being tired out, they are still worrisome enough for the player to consider withdrawing wounded units, because they get worse as they take more damage.

This effect of wounds also provides an opportunity to make the “Berserk” buff in Eador much more different than its counterparts in other games. A unit which goes Berserk does not suffer the penalties for being badly wounded. This makes advanced Warrior heroes quite dangerous, and it also makes the Berserker unit one of the most efficient cannon fodder available.

MORALE:

Units and heroes also have morale, unless they are undead or are constructs.

Morale ratings can change through several ways. The most common change is from winning battles, which increase the morale of units by one point, in addition to any morale boosts from having slain an enemy personally. The demise of allies in adjacent tiles happens to reduce morale too. Also, certain spells either reduce or increase morale.

Morale acts as a modifier to units’ attack ratings; higher morale leads to greater attack bonuses, which start to come into effect when it goes higher than 10. There does not appear to be a ceiling limit, so a player on a roll of victories can have high-morale units dishing out more damage than they should.

However, once a unit’s morale goes below 5 points, it starts to suffer penalties. When it reaches zero, the unit goes out of control. It refuses to attack the enemy, or even do anything. It may even panic and run all over the place randomly.

Interestingly, although units have a stated morale statistic, this acts as a threshold instead of a limiter. The morale of a unit can go much higher than its stated rating, but this elevated morale is difficult to maintain because it will ebb over time. Conversely, if morale goes below the rating, it will recover over time.

This also means that for units which have ratings of higher than 10, they will already have attack bonuses at 100% morale.

As mentioned earlier, the stability of a party affects its morale. The modifiers from it are applied each turn, meaning that a party with compatible alignments can recover from morale damage a lot quicker. However, a positive modifier does not impart any increase beyond 100% morale.

Morale is also a way to resolve battles with, but this is almost always out of the player’s control and rarely happens. Once all of the units on one side have their morale reduced to zero and are broken, the other side is given the choice of ending the battle, or to slaughter the cowards.

HUMAN TROOPS:

If the player expects Eador: Genesis to give the player the choice to field troops other than humans, he/she would be disappointed because it does not allow the player to do so freely. However, this does not mean that the game is limited to just human troops; non-human troops are made out to be exotic troops instead.

Unfortunately, this also means that it is easy to come to think that human troops are the most mundane troops which the player can field. Indeed, this seems to be the case for most Rank 1 and Rank 2 human troops, which have non-human counterparts which are far better at the same roles.

There are a few exceptions, though not always for reasons which are kind to them.

To cite some examples, the aforementioned Berserker makes for efficient cannon fodder. Next, the Militiaman is cheaper cannon fodder, but only for when neither unit can make a dent against tough enemies. After that, Slingers are only ever desirable for their special buildings (more on this shortly).

The player is more than likely to just recruit these low-rank units as meatshields, or just construct their associated buildings for the building options which they would unlock.

Rank 3 and Rank 4 human troops, however, are far, far more worth the trouble of recruiting. However, the player will have to make some tough choices, due to mutually exclusive options for the recruitment of units.

Anyway, some human units are notable for being particularly troublesome when fought as enemies. Of these, the Cleric is the most frustrating to deal with because they have the ability to heal allies from far away and even resurrect them once they are of a high enough level.

As for the story-related reason on why humans are the most common troops in the game, it is that humans are the most prolific species and the most susceptible to the will of immortal beings. Indeed, the game does not hold back on its veiled contempt for the human race, though there is canonical lore which rationalizes this.

RECRUITING HUMAN TROOPS:

Not all human troops can be recruited; the player must construct their associated buildings, yet the stronghold only has so much space.

For Rank 1 troops, only four options out of 12 choices can be made available for recruitment; the options reduce by one for each subsequent rank.

The units’ associated buildings do not merely unlock them for recruitment; the buildings can also be upgraded into something else, usually buildings which grant the option to recruit special guards or which grant economic bonuses to the stronghold (or penalties, in the case of criminal establishments and necromancer’s lairs).

A notable example is the Watchtower, which is the upgrade for the Slingers’ associated building. The Watchtower allows the player to hire the Border Watch, which extends a province’s sight range by one.

RACIAL ALLIANCES:

As mentioned earlier, non-human troops are exotic troops and they are usually enhanced counterparts of human units. However, the player is not able to field them outright.

For Rank 1 and Rank 2 non-human troops, the player will need to cement alliances with their associated non-human races. However, the player can only make an alliance with just one of them.

Making an alliance is not a straightforward matter either – usually because non-humans do not have a kind view of humans. The player must fulfill certain requirements, the most common of which is that the player must have a Hero with a high enough Diplomacy skill, or else the dialogue option for an alliance will not even come up. For certain races, the player must also have a certain level of moral alignment.

Then, the player usually has to run an errand, which tends to involve clearing out a specific type of location. For example, the elves would want the player to clear out mage towers to look for an elven damsel-in-distress. Unfortunately, clearing them out does not guarantee success, because this is a luck-based occurrence.

(In the case of the elves’ quest, the player is treated to a reference to Nintendo’s Mario series if a mage tower does not have the damsel.)

In any battle for a shard, an alliance with any race is permanent; neither the player nor the race can break the alliance (though the race’s regard for the player can change over time such that certain benefits of the alliance can be lost).

Once an alliance has been sealed, the player can take over any province which is inhabited by that race when a Hero chances upon it. The player can also dismiss the native defenders, though this is only desirable if their home is close to the player’s stronghold.

The main benefit of an alliance is that the player can construct their buildings in the stronghold’s foreign quarter. These grant economic bonuses, but more importantly, allow the player to recruit members of their race.

Some races are more desirable than the rest due to their combat capabilities, but they are often more expensive to recruit. For example, Elves, despite being Rank 1 units, are more expensive than most level 2 units and cost just as much to maintain. However, they are the best ranged units among Rank 1 and Rank 2 units, and certainly more than outclass the human Archer.

Some races also allow the hiring of guards which are associated with them. For example, an alliance with dwarfs allows the player to hire clans of dwarfs to defend hill provinces. They even provide bonus income if there are special resources in these provinces (which is just as well, because dwarf clans are not cheap to maintain).

MERCENARIES:

From time to time, the player may be able to recruit mercenary units. These are variants of existing units in the game; usually, these mercenaries start off with already a few levels of experience, and maybe even special abilities.

This makes them quite desirable, but they tend to be prohibitively expensive to recruit. They also already have a medal, which marks them out as mercenaries and doubles their upkeep costs.

On the other hand, mercenaries are the only means of obtaining certain Rank 3 and Rank 4 non-human troops which cannot be fielded through other means. For example, Ogres, Cyclopi and Giants are only ever recruited as mercenaries.

Unfortunately, the type of mercenary unit which is made available is randomly determined. The player can upgrade the tavern in the stronghold for higher ranking units, but that is about the only control which the player has.

EGGS, SUMMONING RITUALS & NECROMANCY:

There are more esoteric means of obtaining non-human units. There are eggs, which require the player to have the necessary facilities in the stronghold before they can be traded for actual units. There are other items which work in similar ways to eggs, such as Golem Ingots and Treant Acorns. These means are desirable because there is generally no recruitment cost.

However, the problem with these means is that they do not inform the player of how much the upkeep costs for these units would be. For example, it is not pleasant to learn for the first time that the Phoenix costs 400 gold and 50 gems to upkeep each turn after hatching one from an egg.

Rituals, which will be described later together with spells, are another way to obtain non-human units for inclusion in parties. Rituals can be used to summon Rank 1 and Rank 2 demons, which are no slouches in combat.

Next, there is necromancy. This is perhaps one of the most overpowered means of recruiting units, because it is easier to perform than others. However, it is also the most expensive in terms of gems; in fact, all undead units require gems to raise and maintain. Undead are generally melee-only units too, but their immunity to stamina, wound and morale effects more than compensate.

(ECONOMIC) CORRUPTION:

One of the ways with which Eador: Genesis differentiates itself from peers in the genre of turn-based fantasy strategy is including corruption - of the greed-caused sort – in the gameplay.

As a player’s holdings burgeon from conquests of territory and explosive population growth, the bureaucracy governing the player’s realm becomes more corrupt. The consequence of this is represented as a penalty on the player’s turn-by-turn income of gold and gems. This penalty increases as the player expands further, but, curiously, recedes if the player loses territory.

Such a penalty is intended to prevent players who are on an all-conquering rampage from getting too much power from their provinces. However, this penalty only seems to be applied on the human player; A.I.-controlled players do not appear to suffer from this penalty. This may seem unfair, but this is perhaps for the better, as will be elaborated later.

However, there are buildings which can reduce corruption by percentages. This can give the player a considerable edge, since it will free up plenty of revenue; incidentally, these buildings also increase income, among other benefits such as reducing unrest. On the other hand, they are very expensive buildings.

There are also random events which can increase the player’s corruption rating or reduce it. These are not very reliable ways to alter the rating of course.

There is a problem with the corruption system unfortunately. The player’s corruption rating is not shown at all, and can only be guessed at from the drain it is causing on the player’s income.

SPELLS:

Being a fantasy game, Eador: Genesis typically has magic in it, and this magic is typically expressed through spells.

Spells are generally the purview of Heroes; even the Warrior can cast spells. Certain units can cast spells too, but there are few of them and they have very limited spell-books with spells which cannot be customized, unlike Heroes’. However, where Heroes consume both stamina and gems to cast spells, units which are capable of casting spells only consume stamina.

To balance Heroes’ spell-casting abilities further, a Hero cannot cast the same spell again, unless he has multiple copies of it in his spell-book. Units do not suffer this limitation, which is a difference that can be confusing at first.

Most spells are quite useful, but only when used where they are most efficient. For example, the astute player is likely to realize that defence-increasing spells are best expended on already well-armored Warrior heroes to increase their survivability even further.

Perhaps the most overpowered spell is Mass Suicide. As its awful name suggests already, it forces all enemy units to hit themselves; in the case of units with resistance ratings lower than 4, they suffer twice the damage from the hit. This makes this spell a must-have against terrifyingly powerful and durable guards, such as the Armada (which is composed of War Elephants, high-level Thugs and Executioners).

Incidentally, some spells are the only way to get certain non-human Rank 4 units on the player’s side, at least temporarily. For example, there are demon-summoning spells which require the player to sacrifice a unit to summon Rank 3 and Rank 4 demons, and a high-level spell to turn a unit into a dragon for a short while.

High-tier spells are not immediately learnable by heroes, who have to increase their magic rating and thus open up slots in their spell-books before they can do so. This is an understandable limitation.

LIBRARIES & SCROLLS:

For Heroes to learn spells, the player must stock the stronghold’s library with spell archives. The initial range of minor spells is only useful for fledgling Heroes, but they quickly become uncompetitive later. To gain more spells, the player must build mage schools, but the player has to make wise choices; the player can only pick four out of six schools, and the choices dwindle for every subsequent tier of spells.

Building mage schools is not a cheap matter either. Most level 1 schools, except the school of sorcery (which packs mostly offensive and buff spells – hence the increased cost), are cheap, but the costs escalate quickly for each subsequent level.

Furthermore, Heroes can only restock their spells at the stronghold and provinces with libraries. Libraries are generally worthless to the province until they are upgraded (which is costly), so they come with significant opportunity costs.

Scrolls are a way to go around this limitation. Scrolls, once consumed, allow the player to stock spells which may not be offered by the schools in the player’s strongholds. Scrolls for common spells tend to be little more than vendor junk, but the powerful ones can give the player an edge, if his/her Hero can place the spell in his spell-book.

Interestingly, there is no method to convert spells in the stronghold’s archives into scrolls. This was perhaps so because it would have been abused otherwise.

RITUALS:

Next, there are rituals, which the player can perform when in the world map. Rituals are spells which affect entire provinces or parties, or both. However, unlike spells, which generally only require gems, rituals require special resources too; lacking them causes the rituals to require gold as well as additional gems.

Just like spells, rituals are also obtained by building mage towers, though each tower upgrade only grants a single ritual. Higher tier rituals are generally costlier and have longer cooldown times.

The usefulness of the rituals is all over the place though. Some, such as a ritual which grants additional movement points to a party, are useful throughout a match. Some others are outclassed quickly, such as the ritual which summons a low-level skeleton into the player’s party.

BATTLES:

Much of the player’s success – or failure – will be attributed to his/her performance in battles, so it is imperative that the player considers the mechanisms which come into play during battles.

First and foremost of these is – surprisingly enough – the terrain. The battlefield is made up of hexagonal tiles, each of which has a terrain type which may or may not impart bonuses or penalties on the unit occupying it. The majority terrain in the map strongly depends on the province in which it is fought.

For example, hilly provinces are likely to have a lot of hill and mountains, thus slowing down land-based parties and giving ranged and flying units an advantage.

As another example, forest provinces result in heavily forested battlefields, which in turn complicate ranged attack tactics.

Next, there are bodies of water. These act a lot like mountains, but also allow hovering units to stay on them (unlike mountains, which only allow flying creatures).

Indeed, if the terrain causes the player to be unable to bring powerful units to bear, these units are very much useless. Conversely, staying on compatible tiles gives units with specific terrain knowledge considerable advantages. These include the waiver of any penalties to moving through them and, in the case of very high knowledge ratings, grant bonuses to statistics.

It is worthy of note here that spells are generally unaffected by terrain, and there are no terrain types which alter units’ resistances.

There may be a lost opportunity for more sophistication in battlefield terrain though. There could have been units which can wade through water, or dwarves which could have been upgraded to be able to move through mountains.

After considering terrain, the player must consider his/her formation of units. This can be done before battle commences, when the player could arrange his/her units so as to occupy conveniently strategic locations. In the case of the player who is being attacked, he/she can perceive the formation which the attacker has chosen (though the attacker always moves first).

Units can be attacked by anyone in a tile adjacent to them, and there is no such thing as facing (e.g. rear armor, front armor). Ranged units also cannot use their ranged attacks on enemies adjacent to them (though they can fire off shots at other enemies).

Therefore, the player should make wise decisions on how enemies would flank his/her own units, and vice versa.

For example, it is a bad idea to attempt to surround a Hydra or any unit with round-attack abilities. Conversely, the player should have meat-shields prevent enemies from flanking the party’s glass cannons.

During a player’s turn, he/she can have each of his/her units performing a move action and/or any other action. This means that the player can attempt to surround a vulnerable unit or have different units chase after different targets, among other decisions. This can be utilized for some cheesy tactics, such as having an advanced Scout class kite enemies (to use a strategy game term).

Also, it is important to know that any unit can retaliate any number of times when it is attacked in close combat. This can result in the unit tiring itself out from repeated retaliations, which is a piece of knowledge of particular importance when developing a powerful advanced Warrior.

Finally, spells which are cast by Heroes during battles consume gems which could have been used for something else. The player is shown a counter of the gems remaining in his/her treasury, but it still can be easy to exhaust the player’s reserves unwittingly.

RANDOM EVENTS:

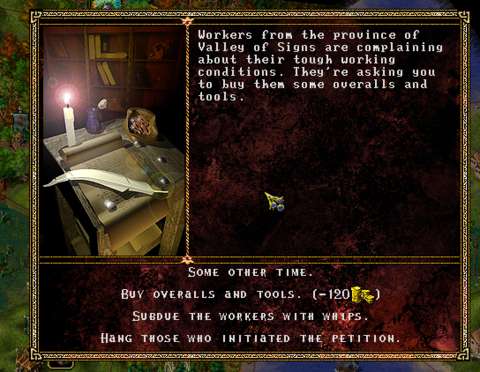

Between turns, the player does not have to contend with just the decisions which the player had made for his/her heroes, but also events which occur randomly. These events present the player with more choices, each having a consequence.

More often than not, these random events present the player with a frustrating choice: pay gold and gems to avoid suffering trouble which is not always the player’s fault, or suffer it and face a strategic setback.

For example, the player might face workers in a province who are asking for special tools for their work. One would think that refusal should not cause much trouble, but the province’s happiness plummets from that decision. Giving them tools does not increase the province’s productivity; any benefit to be had is merely a contribution to the player’s moral alignment.

Sometimes, any decision that the player makes in a random event results in a setback anyway. For example, there is the random event of a province’s population demanding a holiday. Taking any action other than granting the holiday causes the happiness rating to plummet, as well as increasing unrest (depending on the severity of the player’s decision); granting the holiday requires the player to fork out money and lose the income from that province for that turn.

Such random “blackmail” events can be very incredibly infuriating, especially if it occurs early during a match.

This fickle aspect of the game is made even more frustrating by inconsistent results from decisions. For example, brutal and cruel solutions for some random events are efficient, whereas for others, the player is penalized for taking such awful stances. In another example, the player is punished for his/her naïveté in being generous by granting an unknown cult the opportunity to build a shrine to horrible deities, whereas in other variations of the same random event, the player is rewarded.