The Making of Barkley, Shut Up and Jam: Gaiden

If you can't slam with the best, then jam with the rest.

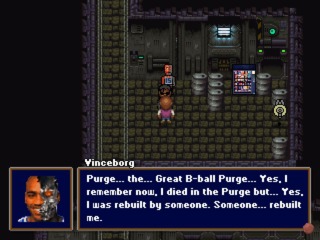

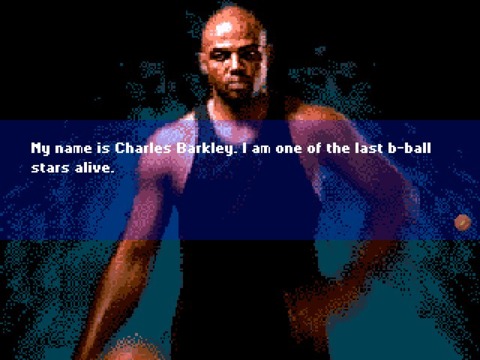

In January of 2007, amateur game designers Eric Shumaker and Brian Raum released a demo for a game they thought only their closest friends would play. But its premise proved too ridiculous to resist. Tales of Game's Presents Chef Boyardee's Barkley, Shut Up and Jam: Gaiden, Chapter 1 of the Hoopz Barkley SaGa thrusts ex-NBA player Charles Barkley into a dystopian future caused, in part, by the events of the movie Space Jam. The game's straight-faced humor and solid execution of Japanese role-playing game fundamentals drew attention from all across the Internet and beyond.

Now, with the release of a Mac-friendly version of Barkley, Shut Up and Jam: Gaiden and the announcement of the game's sequel, Shumaker and Raum are ready to revisit the genesis of this outrageous RPG series. Warning: the postmortem you are about to read is canon.

The number one thing I'm sure people want to know is how you arrived at the concept for this game. Are you both sports fans? Did you play a lot of Japanese role-playing games growing up? When did you decide to make the connection with Space Jam?

Eric Shumaker: [laughs] I like basketball, but I don't actively follow any teams or anything. I don't think you could say I'm a sports fan, although I don't dislike them or anything. There was this Super Nintendo basketball game about Charles Barkley called Barkley Shut Up and Jam; I saw the name and thought it would be really funny to add "Gaiden" at the end.

It's really weird, but we didn't have to think too hard about what we wanted to do with the game. We knew immediately that it would be serious despite having a completely ridiculous premise. I guess when you put the words "Barkley Shut Up and Jam" and "Gaiden" together, chaos dunks, vidcons, neo-shekels, and Hoopz Barkley are just the natural by-products.

We all played a lot of Western and Japanese role-playing games growing up. We were part of the RPG Maker community--a group of people using a free engine to make JRPG-style games--so pretty much everyone there was familiar with the genre. I'm not sure when Space Jam became a part of the game. I think it was just another by-product of the creative flurry that Brian and I had immediately after conceiving the idea.

Brian Raum: I like sports, more so playing than following. I'm a rotten b-ball player, too. But I like it. I was really into the Harlem Globetrotters when I was younger. So yes, Eric came up with the name and contacted me about it asking if I wanted to help, but there's also an ancient Wikipedia edit five or six years ago that kind of informed this game's personality.

I'm almost certain we found it after we had started the game, but I'm not 100 percent sure. On Michael Jordan's page it said, regarding Space Jam, "But some fans disagree whether or not this is canon." That the movie Space Jam is canon to Michael Jordan's filmography? That the events of Space Jam and his joining with the Looney Tunes are canon to Jordan's life and career? Like, Space Jam and AAA baseball are not canon, but his time with the Bulls is? It was funny and strange, and the more time you spend thinking about how something can be canon to existence, the more bewildered you become.

This mystery, and our deliberation, was instrumental in leading us to Barkley 1's ultra-heightened sense of canonicity. But most of all we live in a world where Shaq Fu, Chaos in the Windy City, and Space Jam are actually real things. Sci-fi b-ball heroics are a rich genre that predates our contribution.

With a concept so outrageous, it would be easy to make the whole game super goofy. Instead, the tone of Barkley 1 is a juxtaposition of depressing, desolate future and humorous, almost sitcom-esque scenarios. How did you arrive at this tone?

Shumaker: A big part of it was that we wanted to poke fun at a lot of the games in the RPG Maker community. Back then, the RPG Maker community was pretty amateur--a lot of these games used resources (or entire stories) from other games and did it with a completely straight face. A good deal were very cheesy derivatives of much better commercial games, but they took themselves very seriously and tried to present themselves as completely legitimate.

On Michael Jordan's page it said, regarding Space Jam, "But some fans disagree whether or not this is canon." This mystery, and our deliberation, was instrumental in leading us to Barkley 1's ultra-heightened sense of canonicity."

They weren't bad or anything; they were very cool and interesting. But this attitude of self-importance was something we wanted to make fun of. We took the completely serious tone of all these RPG Maker games and gave it a ridiculous premise. It was the contrast of the tone and the premise that I think made it funny. But it was never meant to be malicious; I think it was an affectionate parody. We love role-playing games, and we love the community we came from.

I think the RPG Maker community was one of the most creatively fertile game-making communities ever, and the big reason was that RPG Maker was a tool for idea guys and not programmers. It gave all those people who did not have the means to make a big game the tools to make their own Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest. They didn't have to focus on tiny mechanical details, but on stories and characters and worlds, and that's what made RPG Maker so attractive to so many.

At the same time, a lot of these RPG Maker dudes lacked a critical sense of self-awareness, and that's sort of what we were parodying with the game.

Raum: Another part of it was just the local culture of the message board we posted at and our group of friends. Before making Barkley 1, there were a thousand other dumb stories, forum topics, games, songs, pictures, alternate identities, practical jokes, and so on that myself and others were involved in. Much of my youth was spent sitting in front of a computer concocting increasingly ridiculous plots to entertain myself and my friends. Kind of a waste of time, but I liked it, and I think we benefited from hanging around in a place where people actively practiced comedy. I don't think for a second I am hilarious or anything, but the "tone" was muscle memory after years of wasteful forum posting. It was what was most fun to write and talk about.

It also fixes problems! People can stomach the melodrama and occasional boredom and inherent JRPG 9999-damage lunacy because of the jokes, and the seriousness grounds the game's conflict in something "real" so the player maintains interest and actually cares to finish the game instead of doing anything else.

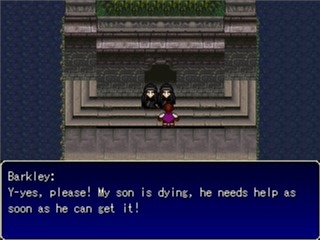

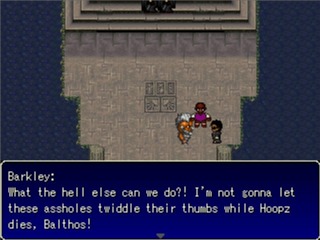

Charles Barkley is the game's hero, but he is also the most cynical toward the world. I remember a lot of funny moments, such as Cesspool X, where Barkley basically didn't give a flip about the drama around him. How did you arrive at his personality?

Shumaker: [laughs] Barkley is definitely a straight man, and I think that's something that's really important in absurd and surreal humor. He recognizes how ridiculous the things around him are, but he also accepts them as part of the natural order of his world. He's not saying "This is so weird. I can't believe this" but "This is stupid. I hate this," and I think there's a pretty significant difference.

I think the most important thing is that the world--and her characters--remains consistent throughout the whole game. There is never a point where the game winks at the player or acknowledges its own jokes. Because really, they're not jokes; they are completely consistent with the gameworld. Obviously it is ridiculous and funny to us that Space Jam was this pivotal world event, but to Barkley it is just part of life. I think that's what defines Tales of Game's style of humor: for most people, the characters are platforms for jokes. But for us, the characters are the jokes, and by remaining consistent, they maintain the joke.

It's like Hank Hill on King of the Hill: if he stopped being a tight-laced straight man and started telling jokes, he wouldn't be half as funny.

Unless I'm wildly mistaken, the game appears to use a heavily modified version of one of the RPG Maker engines. Why did you choose to use this toolset, and what was the most difficult feature to program into the game?

Shumaker: You're half right! The demo we released in 2007 was made in RPG Maker, but the final game was built with Game Maker. We actually completed the entire game with RPG Maker and never released it. Brian and I worked on the game in RPG Maker, and our friend, programmer Jesse Ceranowicz, ported it over to Game Maker, which is why the game took so long to complete.

The original RPG Maker version was largely the same, except lower quality, save for one area: Liberty Island. Our original idea for Liberty Island wasn't an adventure game segment, but kind of a Western RPG area where the goal was to somehow break into the Statue of Liberty to see Wilford Brimley. It had the same general premise--there was a diabetes cult at the base of the statue, and they worshipped Yelmirb as their diabetes god--but it worked a little differently. You could get in through one of three ways: by impersonating a diabetes cultist, by fighting your way in, or by sneaking in through a side entrance.

It was pretty cool because it offered real choice in a game that largely did not have very much choice, but it was executed very poorly, and in the end we decided to scrap it. Jesse Ceranowicz wrote the adventure game parody segment, and his work was infinitely better than mine, so it was ultimately for the best.

Originally, our intention to release both versions of the game, but as we neared completion, we realized that the RPG Maker version was not nearly as good in comparison and that there was no reason to release it.

We decided to go with GM because it gave us a lot more flexibility. We could do more with the combat system, movement was now per-pixel instead of per-tile, and we could use more visual effects.

Raum: Eric is right: RPG Maker rules. The sheer amount of available, already-formatted resources (for placeholder use or otherwise) make RPG Maker easily recommendable for anyone interested in making RPGs. Even if you don't ever use it to make a finished product, it's an excellent learning tool and great for mapping, prototyping, and scripting cutscenes.

Why make this a role-playing game and not use some other genre? If given unlimited resources and manpower, would you still make this an RPG?

Raum: Unlimited resources is giving me all kinds of virtual Barkley reality thoughts, so that's kind of a hard thing to answer. The game would be different with different capabilities, sure, and maybe would be closer to real-time instead of turn-based. I don't know. It would require rethinking the game from the ground up. I don't even know if the game would make any sense with non-ripped graphics and an origin outside of RPG Maker.

We love RPGs. There are a million things you can do with them, and a million things that have been done with them that everyone has forgotten about. It's a little bit of a letdown when I think up some revolutionary idea, and then digging around online for a while I realize I was already beaten to the punch in 1975 by Moria for the PLATO computer system. But it's depressing when I realize the idea was out there and nobody has done anything with it for 37 years!

There are lots of definitions for what an RPG is, and lots of games that are hybrids of RPG and something else. But I definitely do want to make games about or involving exploration, introspection, planning, growth, discovery, edutainment of course, identity, strategy, choice, consequence, and the absence/possession of information. Abstract role-playing game trappings, such as numbers, menus, equipment, and abilities, make exploration of these concepts direct and immediate.

What were people's reactions to this game, either from the fan community or from the athletes parodied? Did you have any expectations for how this game would be received? Did you ever receive any Barkley fan art?

Shumaker: As far as I know, there has never been a response from any of the people this game mentions, and I'd kind of like to keep it that way! We tried to portray Charles Barkley in a way that we think is pretty positive, but I can only imagine he'd say it was "turrible." Either that or he'd sue us.

We had no idea the game would be this well received. The demo was originally just intended for our group of friends; we didn't think there would be any appeal outside of that. We were floored when sites began covering it and thousands of people played the game. We were shocked even further when the full game was released and it was picked up by huge websites and magazines. It continues to blow us away that people truly enjoy our stupid RPG about a dystopian future caused by the Space Jam.

We are so grateful for the way people have responded to this game, and we really cannot thank everyone enough.

What went wrong with the development of this game, and what would you have done differently?

Shumaker: Brian and I spent a great deal of time brainstorming and planning. We would generally talk for a couple weeks at a time about what we wanted to do with an area and then complete it in the span of two or three days. In a way it was good because we had every inch of the area and writing planned before we started, but it also took a lot of time and halted production. If we could go back, we'd work much more methodically and evenly. The way we worked wasn't fair to Jesse, who was programming the game as we went along.

Raum: Eric is correct on that, plus we had a few bug issues early on. I think we actually did a great job testing the meat of the game, but it was only after the game made it to a wider audience that we realized some large errors. I think some might have crashed the game, but there was also a problem with the music that required Jesse to do some fixes. He actually fixed it really fast, but our small pool of testers didn't have the variety to pick up on those kinds of odd compatibility issues. It wasn't really a big deal since it was a free game, I guess, and we got it fixed very fast, but it was stressful knowing the game was out and something was broken, even for a short time.

When development began on this game, was it always intended to be a series, or was it ever designed as a stand-alone game?

Shumaker: Yeah, it was always intended to be a series. We've got documents going back all the way to 2006 that are specifically about Barkley 2, and the characters of Cuchulainn and Cyberdwarf were originally concepts from Barkley 2 that we decided to use in the original. It was also always our intention to make the second game mechanically and thematically different from the first, while maintaining the same tone and humor.

We decided on the name The Magical Realms of Tir na Nog--Escape from Necron 7: The Revenge of Cuchulainn--The Official Game of the Movie: Chapter 2 of the Hoopz Barkley SaGa before the original game was finished, and it's even in the credits of Barkley 1. I have no idea why we stuck with it.

On November 28, 2012 developer Tales of Game's Studios successfully launched the Kickstarter campaign for Barkley 2--roughly four years since the original's release. The game is a departure for the young developer, both in design and in the abuse of licensed properties. Until the game's release, you can check out our video preview for the game below, or play some of Shumaker's favorites from the RPG Maker community: Space Funeral, Wilfred the Hero, Sunset Over Imdahl, and Yume Nikki.

The Complete FALLOUT Timeline Explained! Warhammer 40k: Darktide - Path of Redemption | Update Trailer SAND LAND - Official Darude Sandstorm Trailer Is Fallout 76 Good in 2024? No Rest for the Wicked - Official Steam Early Access Launch Trailer Battlefield 2042 | Frontlines Mode Returns - Time-Limited Event Trailer 21 Details You May Have Missed In Helldivers 2 Stellar Blade - Official "The Journey" Behind The Scenes Trailer | PS5 Games Zenless Zone Zero - Official Koleda Character Teaser Trailer | "Bite At The Site" PUBG MOBILE | SPYxFAMILY Collaboration LIVE Now! Genshin Impact | Version 4.6 "Two Worlds Aflame, the Crimson Night Fades" Trailer The 11 Creepiest Vaults Of Fallout

Please enter your date of birth to view this video

By clicking 'enter', you agree to GameSpot's

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation