Neverending Nightmares: How OCD Inspired a Psychological Horror Breakthrough

Developer Matt Gilgenbach's upcoming horror adventure is not about ghosts and ghouls, but about the terrors within the human heart.

The girl stares at me as blood dribbles from the sides of her mouth. I peer down to see that I have driven a blade into her abdomen.

And then I awake with a start.

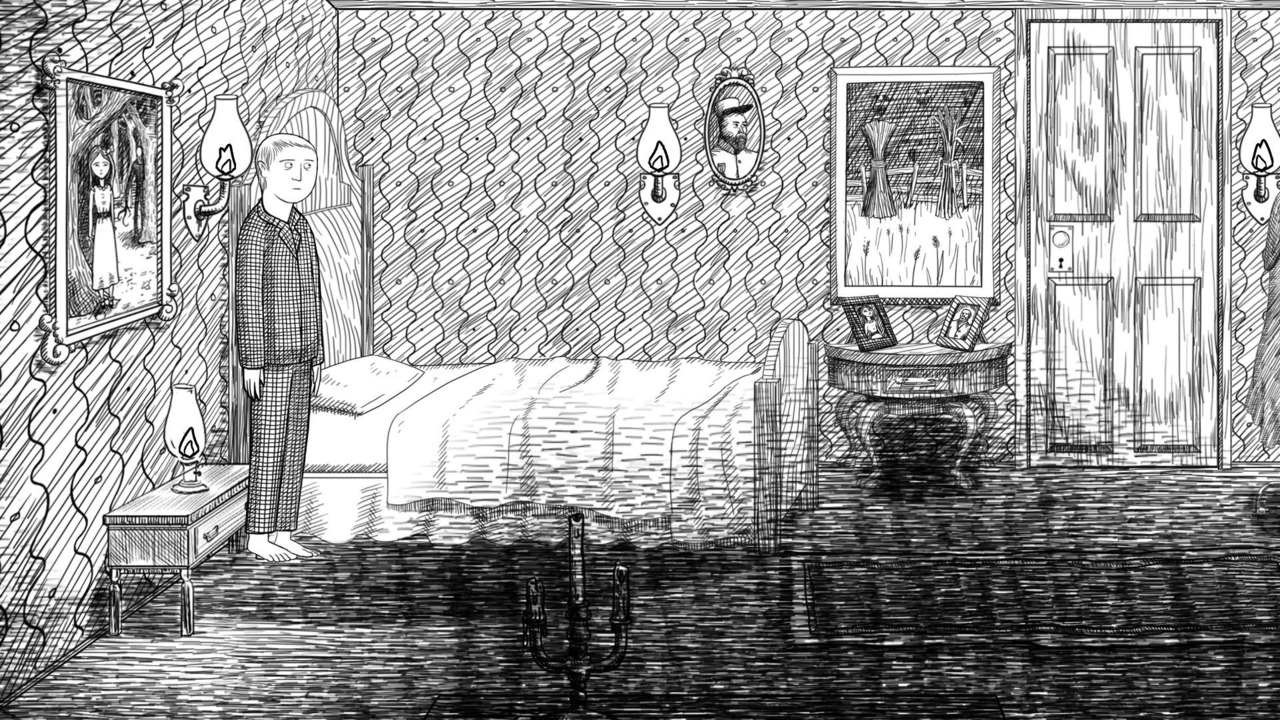

It must have been a dream. I rise from bed and slowly shuffle down the hallway, which is decorated with photographs of military men and the young girl in my vision. Clad in my pajamas, I see a dark entrance leading to the basement. As I walk further in, the darkness engulfs me and tensions rise.

And then I awake with a start.

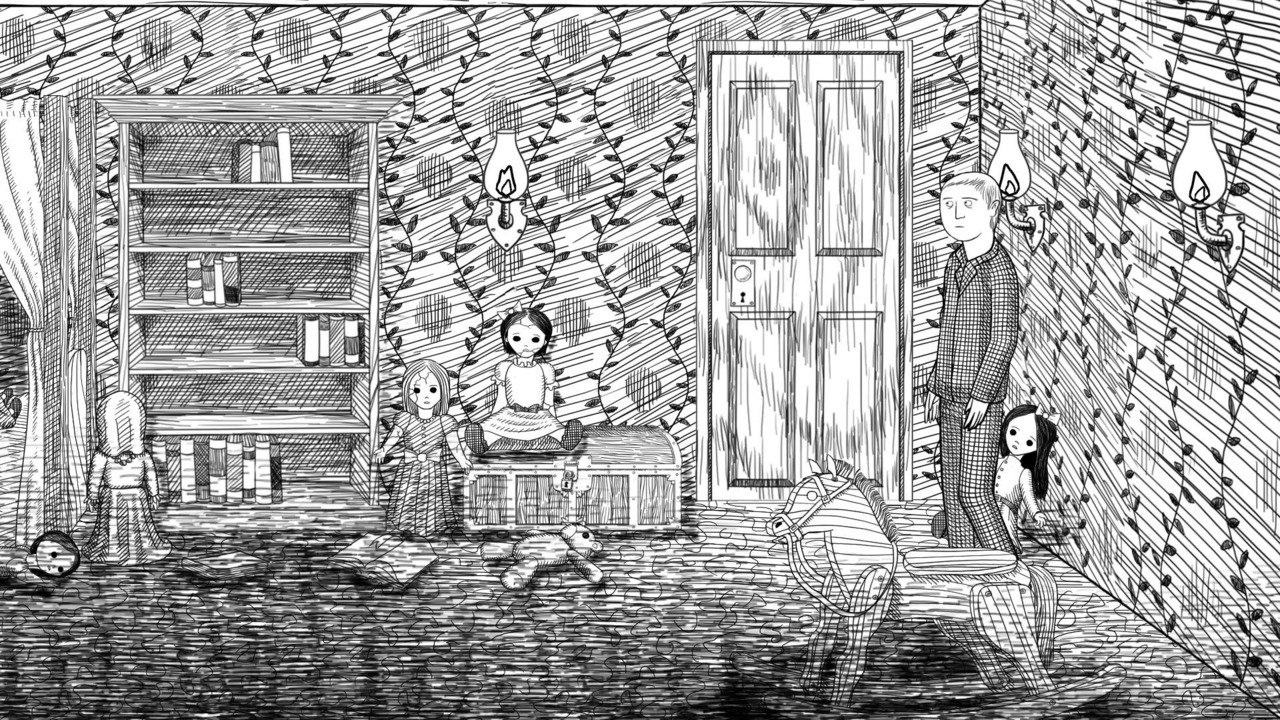

The experiences are nested within each other, cluing you in to how Neverending Nightmares earned its title. This psychological horror game comes from developer Matt Gilgenbach's considerably clever mind, though the game's future is still undetermined: the project is currently live on crowd-funding site Kickstarter with 24 days left to go and about 27 percent of its funding goal reached. How Neverending Nightmares is being funded isn't what makes it interesting, however, but rather the concepts behind it, and the dark experiences that inspired it. As Gilgenbach states on the game's Kickstarter page, "Neverending Nightmares is a psychological horror game inspired by the real horror of my battle with obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression."

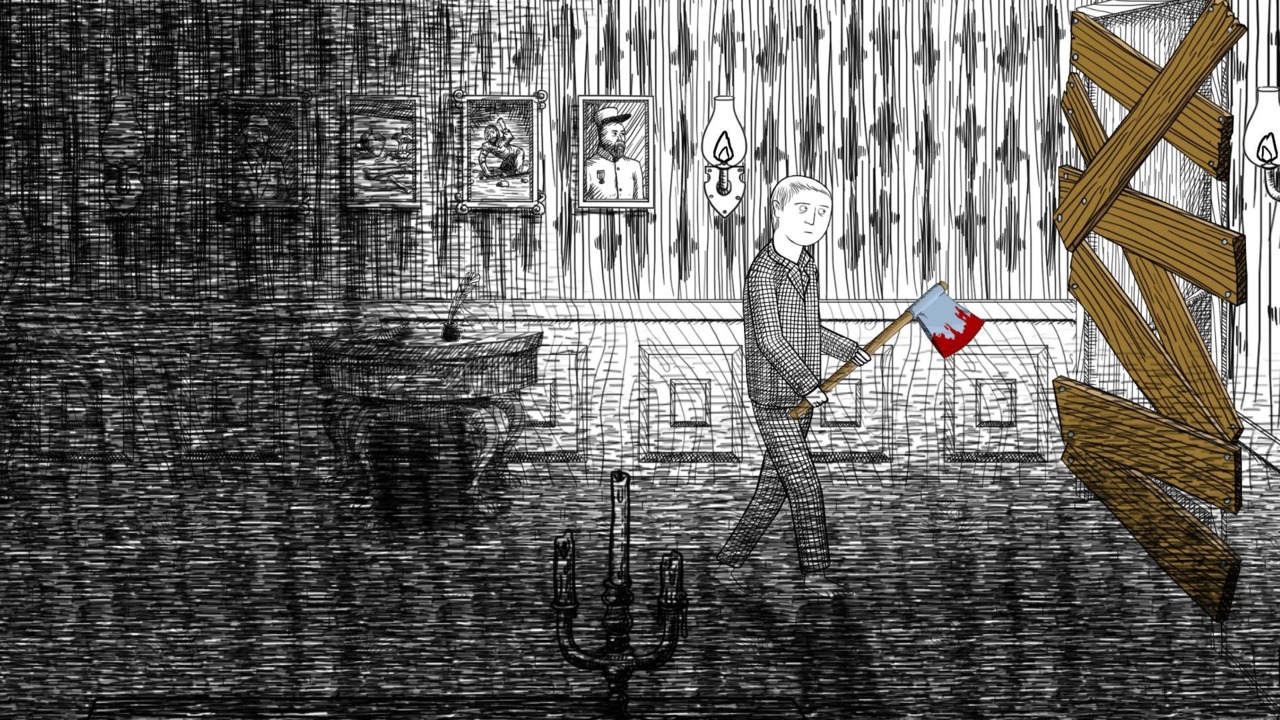

After playing a short demo of Neverending Nightmares, I noted the obsessive elements bleeding from the source material. After each awakening, the repetition of that hallway, of the photos on the walls, and the ticking of a grandfather clock all wore on me, making the visual differences stand out all the more when they appeared. After one awakening, a bloody axe appeared at my bedside. It was a frightening turn of events, but also brutally comforting in the way its reddened blade provided contrast to the shadowed room, providing something new and vibrant to look at. When I caught up with Gilgenbach, I wanted to know more about the game's inspiration, and how his experiences with mental illness would manifest within the game.

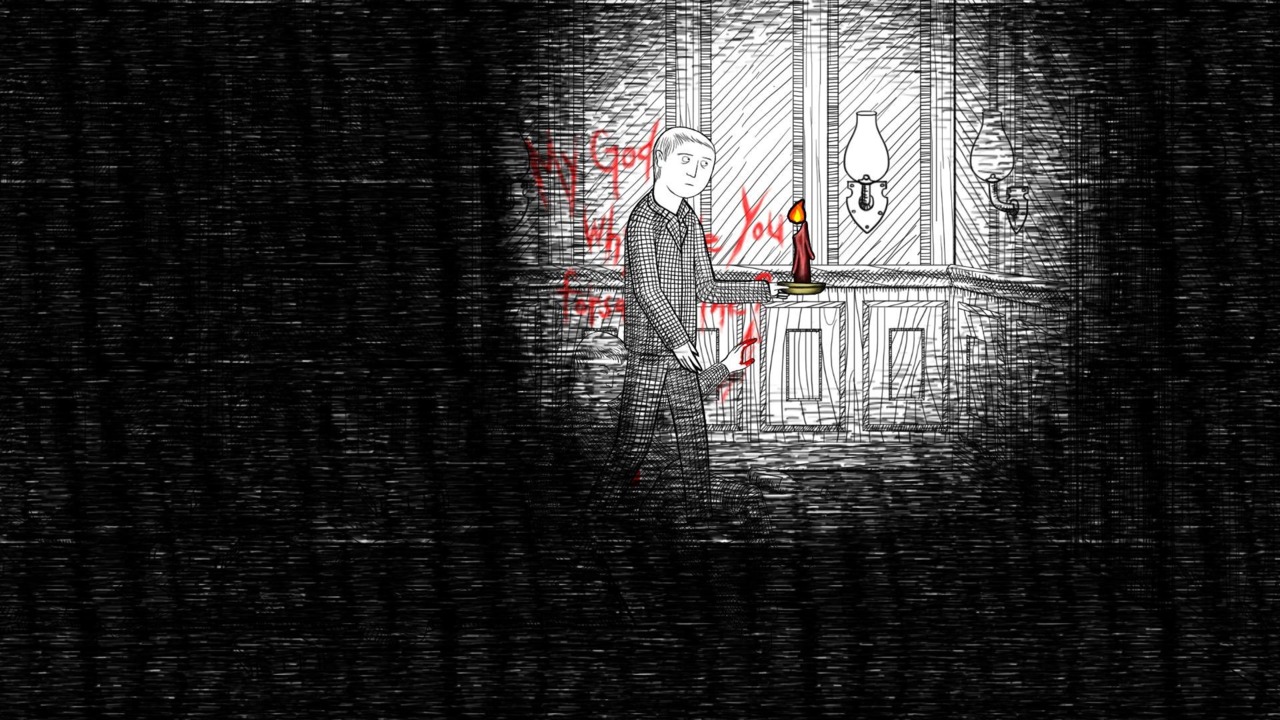

"…even though you are hiding, you are still at risk."

"I suffered very badly from 2001-2003, and everything felt completely bleak and hopeless," says Gilgenbach. "It was so hard to just walk around and do the everyday tasks like get out of bed and go to classes. I am trying to create that feeling in Neverending Nightmares. The mood of the game is so oppressive that walking around almost feels difficult. In addition, I am channeling very specific imagery from intrusive thoughts that I've suffered from because of my OCD. Intrusive thoughts are these crazy thoughts that your mind comes up with for the sole purpose of upsetting you. In my case, I've struggled with thoughts of violent self-harm. I've actually re-created some of my visions in the game like pulling the vein out of my arm or tearing out an arm bone.”

"Finally, a lot of the themes of the game's story are obsessive worries that I constantly think about. I don't want to give too much away about the story, but I am definitely trying to make it very personal."

This is dark stuff indeed. We often associate horror games with the supernatural, but for many sufferers, these themes hit close to home. I'm no stranger to depression: the early '90s were a blur for me after a suicide attempt that led to over a dozen hospitalizations for mental illness. After speaking with Gilgenbach, I returned to the Neverending Nightmares demo once more, my memories of those difficult years fresh in my mind. There comes a moment when you head back down the hallway, though the trek is much longer than before. You use the bloodied axe to smash open a barrier, hoping to escape from the darkness that's growing and filling the space behind you. You leave the shadows behind, only to find a shocking sight--and to awake once more.

Only this time, the nightmare has changed.

This endless hallway, this encroaching murk--they reminded me of all those times I could feel the terrifying thoughts creeping up on me. And just as you use an instrument of violence to find respite in the game, so too did I pick up a sharp object in hopes of relieving the pain. And like Neverending Nightmares' player character, I awoke from one nightmare and into a different one. For me, Neverending Nightmares was scarier than any ghost story or zombie infestation because it reopened old wounds. But it was also a reminder of how far I've come, making the demo a bittersweet and very worthwhile experience.

Of course, a game can't rely on a concept for its power: it has to turn that concept into a meaningful interactive experience. Aside from being a game inspired by mental illness, what exactly is Neverending Nightmares? Gilgenbach compares it to Amnesia: The Dark Descent in the way you shouldn't face your attackers head on, but rather must avoid them entirely. This led me to wonder about a rather specific design dilemma: how do you make the act of hiding a compelling game mechanic?

Says Gilgenbach, "I think the key to that is making sure waiting has a lot of tension. If you are just waiting for a goomba [in a Mario game] to follow a set path, waiting isn't going to be compelling. If you are hiding from a terrible monster that seems unpredictable, that can be really intense! For a horror game specifically, I think the trick is to make it seem like even though you are hiding, you are still at risk. To make the gameplay fair, we probably can't make it so the monsters can still get you when hiding, but I think making it seem like the monster is threatening you is important."

In Amnesia and the similar Outlast, you sprint from danger, hurrying to escape the pursuer on your heels. Neverending Nightmares' pace is a lot more deliberate. You meander cautiously, your character's arched eyebrows and wide eyes communicating trepidation and fear. The Kickstarter page addresses this subject somewhat: "We are experimenting with adding a run button. However, we want to prevent the situation where you are always running. If you were in a haunted house, would you run all the time? I definitely wouldn't. We are currently thinking of ways to have running serve a gameplay purpose but not be something the player will always do." I pressed Gilgenbach on what ideas he and his team have tinkered with regarding a potential running mechanic.

"I've been considering having some sort of endurance mechanic," he says. "While endurance mechanics are usually rather frustrating, I think if we tie it back in to the vulnerabilities of the main character, we might be able to pull it off. I suffer from asthma, and not being able to breathe is absolutely terrifying! I was thinking it might be interesting to have a mechanic where you can only run but for brief periods or your character has an asthma attack and has to stop to catch his breath."

"The other idea I've been toying with is that if you run, you create more sound, which can attract more enemies. That way, walking is safer. This seems like it could be less frustrating but may be difficult to balance from a design perspective. We don't want to have it so that every time you run, a monster smashes your face in, but we also don't want to have a monster only show up in a few occasions--otherwise, then those will be the only time the players walk."

Neverending Nightmares will not be a fully linear game, but will rather have branching paths in which your choices lead you to different nightmares. It's meant to be a short experience that you play multiple times. I was reminded of Home, the 2012 horror game that took a similar approach to its exploration. But Gilgenbach doesn't intend on having all the branches converge so that the key narrative points remain the same each time you play. Instead, Neverending Nightmare will keep its branches alive, which could potentially lead to a robust number of different paths and endings. And creating that many possibilities sounds like a nightmare in and of itself.

"By sharing our experiences, we can really help each other."

"It's hard to say exactly how many branches we will have and if they will converge because it really depends on how the prototyping goes," says Gilgenbach. "Ideally, I would like to use little to no convergence. I think convergence lessens the feeling that you have control over the narrative, so I'd like to not rely on that too much. My goal is to create a tree structure where each intersection in the story leads to two more paths, and each of those lead to two more paths, and so on. That can grow out of control very quickly, so we might not be able to have too many intersections. No matter what, I think we will present a unique take on interactive narrative just because we have a really fresh approach to storytelling."

Of course, all these decisions are grounded in Gilgenbach's desire to channel his experiences in a way that proves cathartic for him and meaningful to players. Says Gilgenbach, "I have been getting therapy for 12 years now, and it really has been life changing. I was able to receive treatment for my OCD that really turned my life around from when I was at my lowest point in 2003. However, there is no cure. It's still a struggle, but I've learned techniques from therapy that have really made my life worth living."

There is, however, a silver lining. "I think the main upside of my struggle is that by honestly talking about what I go through at GDC or with developer diaries, I can connect with people and let them know that they aren't the only one suffering. Because of the stigma against mental illness, it's not something people like to talk about. It certainly isn't something that I was comfortable talking about a few years ago. However, I think it's an important thing to talk about because there are many people who struggle with mental illness. By sharing our experiences, we can really help each other."

How wonderful that a game that made me feel so alone could potentially bring people together. In video games and real life alike, there really can be strength in numbers. And both Gilgenbach and I are fortunate enough to have found that strength.

'Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation