Meier on crafting the 'epic journey,' full keynote video inside

GDC 2010: The creator of Civilization, Colonization, and Alpha Centauri talks about his three decades in game development in the presentation "The Psychology of Game Design (Everything You Know Is Wrong)."

Senua's Saga: Hellblade II Everything To Know The Rogue Prince of Persia - Official New Release Date Gameplay Trailer Genshin Impact - Cutscene Animation "Arataki & Flying Lavender Melon's Rockin' for Life Duet" MultiVersus – Official The Joker Gameplay Reveal Trailer | “Send in the Clowns!” 15 MORE Things You STILL Didn't Know In Zelda Tears Of The Kingdom Firearms Expert Reacts to Ghost Recon Breakpoint's Guns Xbox Studio Closures Are Confusing | Spot On Gray Zone Warfare | Community Briefing Trailer #1 Squirrel With A Gun - Official Announcement Gameplay Trailer Night Slashers: Remake || Official Christopher Smith Character Gameplay Trailer Senua's Saga: Hellblade II - Senua's Psychosis Feature Trailer Street Fighter 6 - 8 Minutes of Akuma Gameplay (High-Level CPU)

Please enter your date of birth to view this video

By clicking 'enter', you agree to GameSpot's

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy

SAN FRANCISCO--At the 2008 Game Developers Conference, Sid Meier was honored with a Lifetime Achievement trophy at the Game Developers Choice Awards, the same honor bestowed on id Software's John Carmack last night. That year, the Guinness World Record holder was also a featured speaker at a Q&A session about building games that "stand the test of time." The legendary game designer has done just that, having just announced Civilization V, the latest iteration of the "god game" strategy series he cocreated back in 1991.

Now, two years later, Meier is the keynote speaker at GDC 2010, delivering a presentation called "The Psychology of Game Design (Everything You Know Is Wrong)." According to the official GDC site, Firaxis' cofounder and director of creative development will be discussing how traditional game design theory is deeply flawed. The official description of the keynote address reads:

"Using actual examples from Civilization Revolution, Pirates!, and other games, we'll look at how including player psychology as a fundamental part of game design can lead us to some strangely counterintuitive places and save us millions of dollars in time and resources. Along the way, we'll learn why AIs should not be too smart, how nuclear weapons are like knocking over a chess board, and why gamers can’t be trusted.

[10:27] The Moscone Center's cavernous North Hall, usually the site of the GDC show floor, has been transformed into a massive auditorium, complete with a shimmering display behind a long stage.

[10:28] GDC workers in florescent green shirts scurry around like day-glo insects, asking attendees to cram as far into the center of the long rows as possible.

[10:32] And we're off! GDC event director Meggan Scavio takes the stage to introduce Sid Meier.

[10:32] "Please welcome the 'Father of Computer Gaming,' Sid Meier!" Thunderous applause.

[10:33] Meier takes a long drink of water, pauses, and begins.

[10:33] "The title of this talk is The Psychology of Game Design: Everything You Know Is Wrong. I thought that would get the juices flowing."

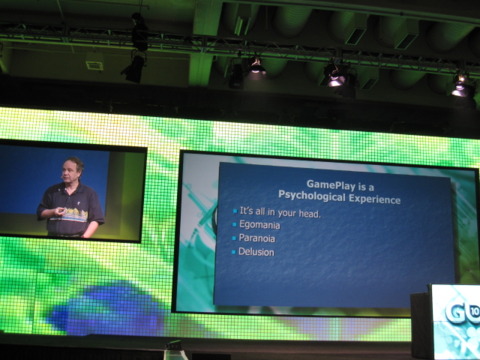

[10:33] Meier believes games are a psychological experience, and the reason he makes historical games is so he can make them as realistic as possible.

[10:34] He said his biggest issue at first was that, by trying to make a game as accurately as possible, he didn't consider what was going on in the player's head.

[10:34] A slide lists several concepts: egomania, paranoia, delusions.

[10:35] "If you play civilization, you are an egomaniac. It says it right there on the box: 'Build a civilization that can stand the test of time.' You're thinking 'Oh yeah, I can do that."

[10:35] Meier outlines another concept, "The Winner Paradox."

[10:36] In real life, not everybody wins. He uses the NFL and NBA as an example--only one team can win.

[10:36] However, in the world of games, almost everybody wins.

[10:37] "People don't complain about that. I don't get letters saying, 'Sid, I win at your games too much."

[10:37] The player is always looking for a satisfactory conclusion to a game, and Meier keeps that in mind in the design process.

[10:37] Another concept: Reward vs. Punishment.

[10:38] When you reward the player, the player gladly accepts it. He doesn't ask, "Did I deserve that? Did I earn that?"

[10:39] On the other hand, if something bad happens to players, it's very important for players to understand why that happened and for them to be able to learn how to avoid it next time.

[10:39] Allowing players to learn is key to replayability, which Meier feels is key to development.

[10:39] Another concept: The first 15 minutes of any game must be compelling. Developers need to let people know they're on the right track early on to keep them engaged.

[10:39] This doesn't negate the concept of difficulty levels.

[10:40] Meier isn't advocating giving games an elastic difficulty setting.

[10:41] In the past, he advocated four difficulty levels. Now, he believes there should be nine, as Civilization IV has.

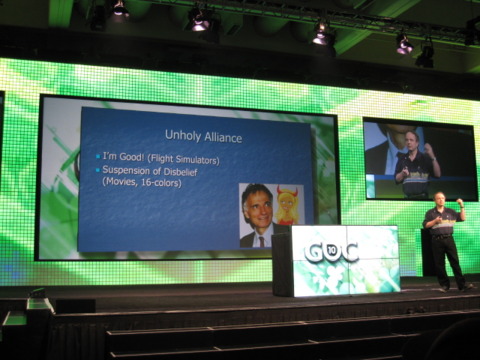

[10:41] New concept: "The Unholy Alliance," with the slide showing Ralph Nader with an attractive cartoon female devil.

[10:42] "I should trademark that term," he says, and a "TM" symbol appears next to the words.

[10:43] This concept makes players want to feel as though they're good. This was the case with flight simulation games, which started out simple but eventually became so realistic that players got confused and turned off to the genre.

[10:43] Another part is the player's role--players need to suspend their disbelief.

[10:44] They need to take on the role, whether it's king of a civilization, a railroad tycoon, or a "cool pirate."

[10:44] Meier is not using a teleprompter; he's just shooting from the hip, which is impressive.

[10:45] He says old-school game developers got really good at the suspension of disbelief because they only had 16 colors to work with.

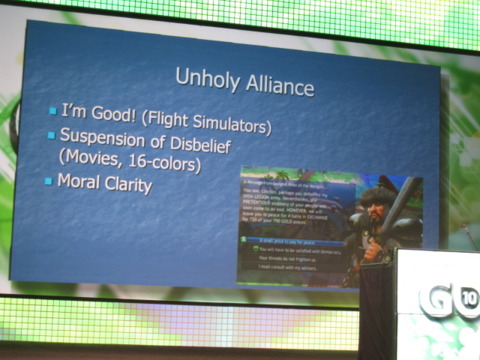

[10:45] Next concept: Moral Clarity.

[10:46] He uses the example of the leaders in Civilization Revolution, who remain defiant even though they only have one city left.

[10:46] He said play-testers thought that was unrealistic.

[10:47] However, if the leader is begging for his life, that would eliminate the moral clarity. "I want to get Genghis Khan, not have him beg."

[10:47] Now for a new concept: Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD).

[10:48] He likens the relationship between developer and player to the Cold War.

[10:48] He thinks either party can totally mess up the balance.

[10:49] He talks about a stillborn adventure game at MicroProse that had players go to a benevolent king at the end of the game…only to find out the king is evil and be sent back to the beginning.

[10:49] At design meetings, the developers thought it was very clever.

[10:50] He said, "Players aren't going to think that's cool! They're going to think they just wasted eight hours of their lives!" The project was canceled.

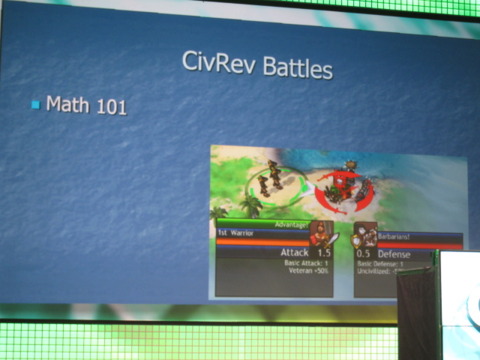

[10:51] The time when I realized that player psychology was not tied to rational thought was designing the battle system in Civilization Revolution.

[10:52] The game shows the odds of battle before the battle starts, and as a mathematician, he looks at a 3-to-1 battle rationally.

[10:53] Players don't think that way.

[10:53] Players will say, "I was in a 3-to-1 battle, and I lost!"

[10:53] "Well, statistically, you will lose every once in a while."

[10:53] "No! I had 3! That's big!"

[10:53] When the situation was reversed, he asked a player how he felt when he won a 1-to-3 odds battle.

[10:53] "Don't you feel that's wrong?" asked Meier.

[10:54] "No, not at all! I did everything right," said the player.

[10:55] He also found players were fine losing 2-to-1 battles, but would freak out when they lost 20-to-10 battles. "I had 10 more! It's not fair!"

[10:55] Players would also complain about losing two 2-to-1 battles back to back, so Civilization games now take into account past battles.

[10:57] Meier admits all these psychological concepts are counterintuitive, but they are important.

[10:57] Now Meier is going over his past mistakes in a section called "my bad."

[10:58] The first Civilization was real time, but Meier found that this made players more of a observer than a player.

[10:58] The motto was "play to be the king," and once it went turn based, players began to think more and act more kingly.

[10:59] Another mistake in the Civilization evolution was "Rise and Fall," which would have a player's fortune crumble before a triumphant comeback.

[11:00] What they found was that once players started doing badly, they would simply load a saved game. "So Civilization isn't about rise and fall, it's about rise, rise, and rise."

[11:02] Next up was the tech tree, which was originally randomized so people couldn't simply go for iron working in order to get to gun powder. They also planned for Sim City-style natural disasters that could bring a civilization down.

[11:02] "You do that, paranoia sits in. Players starts to think the computer is out to get them."

[11:03] Another past mistake was "The Dinos Game," a title that they tried to create in three different versions: a card game, an RTS game, and a civilization game.

[11:03] And now he lists Civilization Network as a mistake, even though the Facebook application isn't even out yet.

[11:04] He thinks Facebook is a fun world to bring the Civ franchise into.

[11:05] One concept that he thought would be cool was to let players exchange gold. Slight problem, though--no testers ever gave any gold to anybody else.

[11:05] "Not sure what this says about the fate of mankind," he jokes.

[11:05] Now onto a new section: "AAA Games on a shoestring."

[11:05] The first rule: Use the player's imagination.

[11:06] If you can make players imagine off-screen action, then you've saved money you would need to create those assets.

[11:07] He uses the text-alert boxes in Civ Rev as an example. In one, players get a message saying "The Sultan of Zanzibar has sent you a gift of a dozen dancing bears."

[11:08] There is no Sultan of Zanzibar in the game, nor are there any dancing bears. However, the player--already playing a monarch--is inclined to believe those things exist.

[11:08] Another tip: "Tap into what the player already knows."

[11:10] That means using character designs that players will recognize. In Pirates, that means giving the bad guy a black mustache so he'd be easily recognized.

[11:11] Now, Meier is going to discuss the "Role of AI."

[11:11] He thinks that AI needs to be part of the overall experience but should not be considered a person.

[11:12] He warns that making the AI do surprising things will have bad effects either way. If it does something bad, the player will assume it's stupid. If it does something overly clever, the player will assume it cheated.

[11:13] Meier likes to think of the AI as a metric. It will make the players better and better and will give players feedback. In the case of Civ Rev, the leaders give feedback, since they're the "only friends players have in a game."

[11:13] Next topic: "Protecting the Player."

[11:14] Meier thinks the prime duty is to protect the player from him/herself. Another job is to deal with load/save issues.

[11:14] "I've seen time and time again players who save before every battle so they always win."

[11:15] Civ Rev gets around this by saving the battle data before a battle so the outcome will remain the same. "Ha, ha, ha!" jokes Meier.

[11:17] He also warns against overcustomization in games. He feels turning too much to the player is dangerous and is essentially letting the players do the developers' jobs.

[11:17] Meier also feels cheats are questionable.

[11:19] One build of a Civilization game had cheats on the main menu, which would let players run over pikemen with tanks. Meier felt the players should play the game first, so he ordered the cheats buried.

[11:19] Meier is a big fan of mods, however.

[11:19] Next topic: "Listening to the Player."

[11:19] The first tenet is to listen to what players are really saying.

[11:19] Just offering solutions to complaints about one part of the game may break another part of the game.

[11:20] He thinks it's more prudent to drill down to the psychological reasons behind a player's complaint.

[11:20] Another concept to take into account is the player's emotional state.

[11:21] "You have to ask yourself how to take away a negative emotion and how to reinforce a positive one."

[11:21] Being aware of a player's personality is also vital.

[11:21] "So what is the point of all this, you might be asking?"

[11:22] It's what Meier calls "The Epic Journey."

[11:22] No matter the type of game, each is an epic journey.

[11:22] Meier offers several tools to make a game "feel more epic-y or journey-y."

[11:23] The first is interesting decisions--make sure to pack your game full of them.

[11:23] Choices that offer two interesting paths are the most powerful because players will be wondering about the path not taken.

[11:24] Learning and progress are also important. Players need to feel that they're always progressing, always learning.

[11:24] Meier thinks a great example is World of Warcraft's leveling system.

[11:25] Another concept is "One More Turn," the idea that the player is leaning forward and anticipating what's coming next. Foreshadowing is a great way to do this.

[11:25] All these concepts lead to the Holy Grail of game design: replayability.

[11:26] "Now you know everything," says Meier, ending his presentation. Thunderous applause.

[11:26] Now it's Q&A time.

[11:26] "I'm sure much of what I've said is wrong so I'll be more than happy to take your questions."

[11:27] First question: "How do you tell your animators and artists what your vision is?"

[11:27] Meier will often build a prototype himself to help show them how the art fits into the big picture.

[11:27] He thinks it's also important to let artists be artists.

[11:28] "Games, as a collaborative medium, need to allow everyone's talents to work."

[11:29] Next question: "Do you think that this egoistic approach to games is prefigured by the themes you give them, since you're telling them you're going to be a king or a railroad tycoon?"

[11:30] Meier thinks that the whole point of games is to let people go places they can't in real life. "What you're looking for in a gameplay experience is something that will take you out of the real world and into a cooler world…and at the end of the day, that world seems cooler if it's been around for 3,000 years."

[11:31] Next question: "With the limited amount of time people have to play games, wouldn't it be easier to make a shorter game instead of an epic journey?"

[11:31] He thinks that people choose the games they want to play with the time they want to play.

[11:32] A Midnight Club developer says his game was "slammed by critics" for being too hard. How do you get players used to the concept that they won't always win?

[11:32] "You're walking uphill there," says Meier, who thinks players get frustrated when they lose too much.

[11:33] Another questioner asks about the increasing trend to make moral choices in games.

[11:34] Meier says that he isn't a fan of those type of choices unless the game is very up front about the fact it is offering moral choices. He thinks that if you're not clear about that, players can become worried they made a poor moral choice, which will take them off the beaten path.

[11:34] Next question: Where will the next great game concept come from?

[11:35] "Where do I see gaming going? I think this is the year of Civilization, frankly!"

[11:36] He says some interesting things are happening in social gaming but also that the "energy and dynamism" of the industry makes it hard to predict where the next big thing will come from.

[11:38] Next question comes from someone who found himself not trying to beat the computer but beat his own score. How does one develop for that type of person?

[11:39] In Civ Rev, he said that the game kept track of how many times a player saved and loaded in an effort to discourage people from trying to artificially inflate their scores.

[11:39] The next question is about social-network games being copycatted.

[11:40] He says that with the Civilization Network, they're just trying to make the best game they can.

[11:40] Next question: Did you ever do something that flew in the face of expectations?

[11:41] He says not really, and he points to the Civ Rev combat system, which he said went to great lengths to keep players in the game.

[11:42] Actually, he did do that by putting ballroom dancing in the recent Pirates! remake. "That could've been on the 'My Bad' list," he jokes.

[11:42] Next question: How are the nine difficulty levels implemented?

[11:43] That's not an easy question, says Meier. He considers the first level to effectively be a guided tour of the game and the hardest level to "kick your ass or you feel like it's not working."

[11:44] Next question: Do you like hard games like Demon's Souls?

[11:45] Not really, says Meier. If he is frustrated with a game for 20 minutes straight, he tends to put it down and never pick it up again; if he feels it's being gratuitously hard.

[11:46] Being asked about blending genres, he feels that "two games are not necessarily better than one." He felt that Pirates! may have blended two genres too much.

[11:47] Last question: "When I was young, I loved the detail of your games. Now, as an aging gamer, I find the choices overwhelming. How do you deal with that?"

[11:48] Meier says he, too, is an aging gamer, and his response to that was Civilization Revolution, which was designed for the non-hardcore audience. "Not that you wouldn't want to play the full PC experience of Civilization V!" he jokes.

[11:48] And that's it!

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation