L.A. Noire: Final Thoughts

The game is finally out, and we take a peek behind the development curtain in our two-part look at this long-anticipated game.

The only thing the cynics in the peanut gallery love more than an underdog is the guy who might not ever finish the race. When L.A. Noire was announced in 2005 as an upcoming "detective thriller," nary a detail was in sight, save for PlayStation platform exclusivity. A year later, a CG trailer surfaced and provided a first look at what the game might look like, before the elusive studio went dark. It was late 2010 before we heard anything about the project again, with some gamers justifiably assuming that the four-year silence relegated the game to Duke Nukem Forever vapourware status--a moniker bestowed upon titles doomed to never see the light of day.

More than six years after development on the game began, Detective Cole Phelps has finally had his day in court, with the game now on sale and critics singing its praise. But a few questions remain: What took so long? Why did the Australian studio go to ground? And where are its sights set from here? To answer these questions, and more, we sat down with Team Bondi's creative and technical leads for candid discussions about making L.A. Noire, what went wrong, how they could have done it differently, and some of the lessons learned in the process. In this first part, we delve behind the scenes into the nitty-gritty of the game's technical wizardry, including building a motion-capture system on theory, mating traditional animation with cinematography, and the arduous task of actually fitting the results on a disc.

Mortal Kombat 1 – Official Invasions Season 5 Gameplay Trailer The Outlast Trials | Toxic Shock Limited-Time Event and Update Trailer Life Eater - Official Launch Trailer Devil May Cry: Peak Of Combat | Vergil: Count Thunder Returns Gameplay Trailer Honkai: Star Rail - Official Aventurine Trailer | "The Golden Touch" The Complete FALLOUT Timeline Explained! Warhammer 40k: Darktide - Path of Redemption | Update Trailer SAND LAND - Official Darude Sandstorm Trailer No Rest for the Wicked - Official Steam Early Access Launch Trailer Battlefield 2042 | Frontlines Mode Returns - Time-Limited Event Trailer Is Fallout 76 Good in 2024? 21 Details You May Have Missed In Helldivers 2

Please enter your date of birth to view this video

By clicking 'enter', you agree to GameSpot's

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy

Team Bondi as a development team is clearly a bigger fan of "show" than "tell," and for this reason, we were eager to see the office space where they have toiled away for so many years. The company takes up the entirety of a large floor in an unassuming Sydney office complex. As the lift doors open, we're greeted not by flashy oversized game props, pinball machines, and beanbags, but rather a humble, huge, unoccupied space. A low-slung coffee table is covered in the latest gaming magazines. Fixed to the wall beside a reception desk are framed discs and cover art for previous titles such as The Getaway--a game brother from a different mother that helped shape L.A. Noire's development. Team Bondi's first-shipped title doesn't have a space on the wall yet, but after surging global sales since launch, we're sure it won't be long before it takes its place alongside its predecessors.

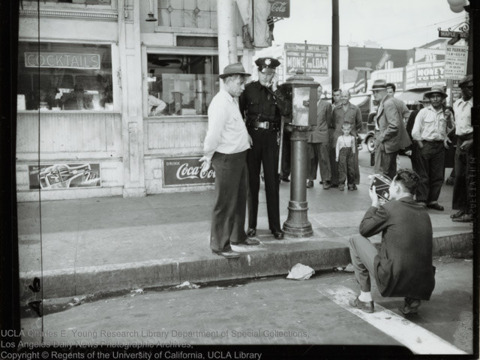

As we pass through the office on our way to a meeting room, we notice that the walls are adorned with character concept art, reference photos of 1940s-style America, cars, and fashion. It's more like a time capsule than an office, and it's this devotion to detail of the era that permeates every aspect of L.A. Noire and drives the people who worked on it for so long.

The final results of this labour of love, particularly the game's unique facial scanning, speak for themselves--but where do you start with a concept as elaborate as this? Technical director Franta Fulin and producer Naresh Hirani took us right back to where it all began: building the tool skeleton to support the game's creative skin.

"People think we were an established team because we've done other projects before. There wasn't a single line of code, there wasn't a single texture, there were no tools, there was nothing to click. No desks, no nothing. A blank office with a few guys from Europe and a few guys from here. From there, it took years to finally get it to the point where it was something to call a team," says Hirani.

Fulin continues the thought; "Someone had to sit down and write the code to read the stuff off the disc before anything could be put onscreen. Every little layer had to be built one on top of the other. I think the first two years of the project was just about building tools."

In 2006, the team began to expand, evolving beyond simply developing technology and starting to put together the first semblances of actual gameplay experiences. But it wasn't all smooth sailing once they had the chance to begin layering content over the subsystems they had built, explains Fulin.

"Another tricky thing was the PS3 wasn't really something that existed. We were working on this game before we had PS3s to work on. Once it did start coming out, we were going through different revisions of the hardware, and Sony would tune a fundamental aspect of the PS3, and we had to rework everything for that. Then they'd change it back again a few months later. So that was part of the challenge, too."

Fulin goes on to discuss some of the bigger technical hurdles that the team was forced to tackle. "Naturally, the [Motion Scan] being the new technology, but other than that, the massive environment. That's a technical challenge for any team; you're working on a massive open world and can go anywhere you want, streaming things in. The level of detail we wanted for this game, as you're driving around looking at shop displays that have accurately modelled things in them. Pulling all that stuff in, there's never enough memory to hold everything you want, so you're constantly pulling things off the disc. Trying to do that in a way that the player doesn't notice, that was one of the big challenges. Making the technology disappear under the gameplay."

While Australia has managed to carve out its own niche in mobile gaming with the success of games like Halfbrick's Fruit Ninja and Firemint's Real Racing and Flight Control, the Aussie industry has seldom been known for its home-grown AAA game development. As a result, both while building the tools and moving on to the game's artistic design elements, Team Bondi faced a fresh wave of tests: finding locals to do the work.

"We found a lot of skill sets. The big related industry is animation, so we found a lot of people with that skill set we had to re-skill. It wasn't the usual situation where you have a big development community you can pull experienced resources out of and build the team quickly. In a lot of ways, we had to become kind of a university and train people up on what it was to make games," says Hirani.

While the development team continued to bubble away in the background, far from the prying eyes of curious fans and media, the game's first real introduction to the public was with a look at the game's Motion Scan face capture technology. We asked if there was ever a risk that presenting it publically that way ran the risk of selling L.A. Noire more as a demonstration of the technology under the hood than the game it was created to serve.

"Maybe with other studios, but not with us. Brendan [McNamara--studio head, and the game's writer and director] always believed it was a tool to sell a story, and, at its very core, it's a gameplay mechanic. We never used it as a sales pitch. For us, it was all about how we can make an immersive world," says Hirani.

"I think what's unique about this is that the core tech drove the gameplay. It is the gameplay; you read the face and you make choices around that. From the early point, proving that this was going to be fun was critical. [The scanning] had to be captured in one massive bulk because people's faces change, etc. One of the hardest things was keeping the team focused and telling them 'Hey, it's OK. This is all going to come together in the end!'" he laughs.

Where many developers record voice-over audio and then animate character mouths to match the words being spoken, Team Bondi's approach merged two dissimilar types of technology: old and new. Since capturing full-body scanning of each actor's performance was ruled out early in the game's development due to technical limitations, a mixture of the two techniques was used. Human-looking heads needed to be merged with traditional body animations.

"It didn't pose itself as a problem so much. We knew we had two sets of data, and we have really smart programmers who knew they would have to work together with the tech side of the game. Those two teams came up with a process where we could preview the performance of the head, and we could also preview the performance of the motion capture and the actors knew what to do. Obviously, there were other issues with frame rates and animation and the usual, but the guys managed to pull off, in most cases, a wonderful pairing between the heads and the faces. I think what the issue may be for some people is that the heads are so lifelike that people may overanalyse it and say, 'Well, why is his hand there?' and so on. I think people are just so drawn in by the expression on the faces," says Hirani.

With almost two dozen hours of in-game human facial capture making the final cut, getting this beast into players' hands was a challenge in and of itself. Though the PlayStation version ships on a single Blu-ray, the Xbox 360 edition of L.A. Noire came in at a larger three DVDs, scaled down from almost six. While no content was cut to make it fit, Fulin and Hirani explain that each platform has its own idiosyncrasies, each playing its part in optimising and compressing the game to fit.

"The scale of the game--that it's open world and hitting that rock-solid 30 frames per second--is what every developer wants to do, but certainly there are areas where it can look unbalanced. I think we did pretty well considering the level of detail we've got." "[Compression] was everything. We liaised with Microsoft and Sony to get ideas. It was about chipping away at what seemed like an insurmountable problem. You come up with an idea and think it will be really awesome, and then you finally get it working and it saves 1 percent off the data size, and then later on you get another idea, and there goes 5 percent," explains Fulin.

"It was very, very late. Surprisingly late in development," says Hirani. "We were pushing on it for probably two and a half years. It was a few megabytes here and there, compressing it down and down, trying old-school techniques people don't do anymore, hoping it might work, saying, 'Let's try, it might work on this particular texture type,' or using a different channel--all manner of things. It took a long time and was scary how late we were doing that."

Fulin sounds like a man who fought the game's battle of the bulge as he continues, "I don't want to get too technical, but it's all about compression mostly. We would swizzle the data around before compressing it. We tried all sorts of compression techniques. We had different compression systems on 360 versus PS3 because some things we can do on the SPU [synergistic processing unit] on PS3, but we can't do them on 360. The 360 had some native formats that the PS3 doesn't support for textures and vice versa. It was all about mixing those up. While we have feature parity between the two platforms, a lot of things under the hood are quite different."

With the technological foundation built, it was time for the design and gameplay teams to begin working on bringing the look and actions behind the game to life, creating a realistic, lived-in world that was fun to play and explore. Check back next week for the second part of our final thoughts on L.A. Noire, where we speak with the game's art and gameplay lead designers and producers.

In the first part of our Final Thoughts on Team Bondi's L.A. Noire epic development, we sat down with the people who built the things you'll never see--the lead technical crew responsible for architecting the framework that the gameplay and artistic elements piggyback onto in order to create the game experience. As technical director Franta Fulin so eloquently put it during our chat, "If people don't notice, then we did something right."

The second and final portion of our feature focuses on the things that you did see and play: the art and gameplay that made L.A. Noire the fresh and well-received experience that it is. Eager to find out the iterative process that the teams went through to get to that final result, we chatted with art director Chee Kin Chan, production designer Simon Wood, lead designer Alex Carlyle, and Team Bondi's founder, studio head, and the game's writer and director, Brendan McNamara. Read on for their thoughts on getting the game across the line.

As the tech team discovered while attempting to build out the internal workings of the game, the limited number of local developers with large-budget game experience forced Team Bondi to seek out fresh blood.

Mortal Kombat 1 – Official Invasions Season 5 Gameplay Trailer The Outlast Trials | Toxic Shock Limited-Time Event and Update Trailer Life Eater - Official Launch Trailer Devil May Cry: Peak Of Combat | Vergil: Count Thunder Returns Gameplay Trailer Honkai: Star Rail - Official Aventurine Trailer | "The Golden Touch" The Complete FALLOUT Timeline Explained! Warhammer 40k: Darktide - Path of Redemption | Update Trailer SAND LAND - Official Darude Sandstorm Trailer No Rest for the Wicked - Official Steam Early Access Launch Trailer Battlefield 2042 | Frontlines Mode Returns - Time-Limited Event Trailer Is Fallout 76 Good in 2024? 21 Details You May Have Missed In Helldivers 2

Please enter your date of birth to view this video

By clicking 'enter', you agree to GameSpot's

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy

"We have a good relationship with the [local] colleges and TAFEs, and we would go along and handpick who we thought were the top graduates. So we really tried to get in at the foundations. It's rare that a AAA game gets made in Australia, but the majority of people [on the team] are Australian," explains Chan.

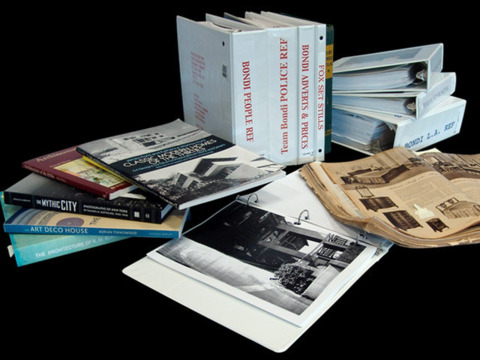

Once the studio had filled the seats required to take on the job, it was time to get cracking on building an authentic re-creation of the time period. Of course, while developers working with fantastical timelines and locations have the creative freedom of being untethered by reality, research became an all-consuming element of L.A. Noire's faithful reproduction of the era. But with clothing, cars, architecture, dialog, values, and language to get to grips with, where does a studio begin with such a massive undertaking?

"The short version is: Brendan had contact with various universities in America: UCLA etc, and they had very large photo collections, so we were able to access the photographs used on the front pages and second pages of every single newspaper from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s," says Wood. "We literally wore Mickey Mouse gloves, and we literally thumbed through each individual single photograph and scanned them in high-res. We then did the same in the geography departments of these universities and did the same to the stamp collections. We then had photo teams in America formed up of photography graduates, and we had them walk up and down the full length of L.A. photographing every single landmark building that still stands today. On top of that, we had similar things going on for costumes, props, clues, and everything else."

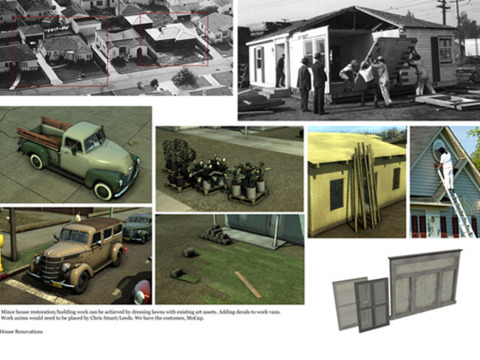

Modern Los Angeles is a city known for its smog-filled air and miles of highways, and while the city has changed over the past 70 years, it has always juggled the glitz and glamour image of the showbiz city alongside a sombre colour palette. The pair explained that the game's postwar time period necessitated that they bring some much-needed colour into the world, using shop windows and the wares being sold within to help break up the bleak environments to stop them from becoming flat and one-dimensional.

"I was going through this Sears catalogue and I found a list of the top 10 paints ever used, you know, for houses, and I found all the stains for all the decking and fence posts, and we used them. We found a really good balance between lighting the environment (with all those L.A. sunsets) and the locations. Sure, there wasn't much colour reference material to work with, but we did find some, and we instantly went for that chrome pastel colour in L.A., and we built on that. We had a lot of [reference] material on vegetation and sidewalks, and it was all layers. And it all goes back to enthusiasm with the team. Once they saw the world starting to come together and we got past the individual buildings, people really took it in their stride and went for it. They started putting in little details in gardens like upside-down bicycles and that sort of thing for no reason, but we allowed them to run with it," says Wood.

The game transitions effortlessly between indoor and outdoor environments, driving and combat, and interrogation and forensic sleuthing. With such a living world, item authenticity became crucial, with red herrings and legitimate clues appearing in the frame at the same time.

"We wanted to make the world believable, so we didn't put anything in there that was out of place," says Wood. "So the reason why we wanted the guys in the team to run with the ball dressing the locations was because it's really obvious to see the murder weapon if the place is empty and there's just the shiny knife in the corner. We allowed the guys to create the world as they saw it from our reference. There was a lot of internal testing, and sometimes people would walk past something in the game and go, 'Oh, I can't believe I missed it. It's right there!' What we tried to do from the art side of things was create such an immersive experience that you're too busy looking around at the trees and the birds and whatever and then eventually you look past the layers and layers and then there's the thing you need in the corner."

As a result, attention to detail was no longer optional. Every beer bottle, cigarette pack, and handwritten letter was forced to bear the marks of their real-world counterparts. But with that meticulousness to accuracy came a huge time cost.

"We looked at thousands and thousands of props and household items. We had to find the items and then find the colour version of these, and it took a long time, but we paid the same amount of attention to normal props that players might not use as we did to those props they would use," says Wood.

"When we explained it to the team--the need to go down this route--there was no question that [each item] had to be built equally as well as something else, because the team had seen the tech demos, and they knew what we were trying to create. Part of what we wanted to do was trick the player--what is a clue and what isn't? So it was a done deal that they would spend as much time and effort on those things like beer bottles, etc."

"The first 18 months of development, we created a database of about 11,000 articles from the time. The LA Times, the LA Examiner, we had every copy from January 1 to December 31 in 1947."

"One of the really useful things in the pictures were dead bodies; people cut in half on the front page," says Wood. "We literally had this massive database of how many traffic accidents there were, how many crimes there were, and we used those as inspiration for the cases. Some of the cases are based on historical events, some are side missions, and they came from this."

Though it would be easy to take note only of the game's authentic, and at times haunting, musical soundtrack, which includes artists such as Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, and Ella Fitzgerald, game audio plays a significant role in the way that players explore and interact with the world. The trill of piano keys alerts you to the presence of items that can be inspected, and the vibration of the controller (which can be disabled for those after more of a challenge) leads without ever directly guiding. There was some debate among the development team about whether or not to include the cues.

"Audio formed a big part of that. We wanted to be subtle, we didn't want to say 'well done,' and having the music end when you found the last clue and the chimes when you walked past something was an interesting way of not being too obvious but being obvious enough."

"I think it's important for players to drive forward the experience," says lead designer Alex Carlyle. "We wondered whether or not to have no music and let the players just stumble through, but I think the game is big and you don't want to hold the player's hand too much--but you have to be able to enable them to know that if they've found something, they can carry on, and we went for the most subtle approach we could. I think it was important that players felt that sense of progression, though."

Once you've wrapped your head around the lifelikeness of the character portrayals in L.A. Noire by its digital cast, the game's lasting legacy is undoubtedly its interrogation mechanic. The game builds on the basics of branching conversation, moving beyond simple cajole and force techniques, but reading faces and second-guessing motivations was a hugely complex mechanic to get right. Carlyle explains how the system evolved over the course of the game's development.

"Our initial design was a back-and-forth conversation, and obviously we have this awesome facial capture tech, and that was great, but what we wanted was more. We wanted to turn that into a gameplay element and really challenge the player. We went through quite a lot of iterations of the conversation system, and once we had our back and forth, we introduced branching so that players could go down different branches in the conversation, and that added a lot more complexity to the system and also required more dialog. We then put meters up on the screen measuring cooperation and got people internally to test this out, but then we realised that having all these things on the screen wasn't really what we were looking for, and people were finding it too complex. Finally, we boiled it down to this idea of asking questions and exploring branches, and the key part of that was coming up with what to do if someone was lying or telling the truth, and whether we just say, 'Yep, they're lying,' or whether we say, 'No, hang on. I know they're lying because I've got this piece of evidence here to prove it.' And finally that link between the conversation system and the inspection system was what tied it all together nicely, and that brought out our whole game system."

Developers often become so close to their own projects that, even after years of tweaking and external testing, it can be hard to objectively view the way that gameplay systems will work in the hands of those who haven't been involved in the process. For this reason, the design team did have some apprehension about how players would receive the inspection system.

"You ask yourself, are people going to enjoy walking around and looking at everything?" questions Carlyle. "Well, we did, but that doesn't mean that 100,000 or a million people will do the same. I think that, more than anything else, was the litmus test for us. Are people really going to get being a detective, and are they going to enjoy it? And I think there's a large portion of people out there who are saying yes, this is different, and this is slower, but it's a breath of fresh air. And I think that's important for the game industry to try something different and to not always follow the same path, and hopefully people enjoy that."

Muddying the waters of truth by fostering a sense of doubt in the player when connecting evidence, and conducting conversations with mismatched body language, is core to the L.A. Noire experience. Everybody in this city has something to hide, but while the evidence doesn't lie, it becomes a support that forces players to reevaluate what they think they know for fear of punishing an innocent victim caught up in the swirling winds of half-truths and subterfuge.

"I think part of the process when you're setting up the case is that the evidence is clear, and it's not leading the player in the wrong direction," says Carlyle. "I think, naturally, people begin to doubt as soon as you give them the option of accusing someone of lying, and you provide them with a handful of objects, some of which can make the links quite tenuous. I think it's in human nature to start doubting people. We didn't have to try very hard to get people to start doubting as soon as someone starts lying to you in the game. The performances were so good that people immediately could see that. Generally, everyone's a pretty good judge of character in real life--you look at someone and you know if they're being honest or not. So I think as soon as we introduced that to the mix along with a series of objects, people suddenly caught on. The cop medium is so well established--everyone is watching cop shows now, from The Wire to NCIS, and so on. People will naturally fall into that role. We never struggled with that."

"We read a lot of books on psychology and body language, and we learned about things like eye movement. Some of the actors we got are just fantastic, so you just tell them they have to lie and they just know what to do. In some situations, we had to highlight how important a scene was and so on, but we allowed the actors to act."

One of L.A. Noire's feet is firmly planted in the open-world category, and indeed, the city is ready to be freely explored at will. Short side mission shoot-outs and foot chases help to break up the detecting, boosting your experience, which in turn unlocks intuition points to spend during interrogations. The other foot, however, is rooted in a linear story experience. Multiple threads come together to weave one dominant narrative, but we were curious to find out if the development team ever considered shipping the title as a purely linear single-player experience without the distractions of side quests.

"No, definitely not," says Carlyle. "We wanted the side missions from the word go; we wanted to use this as a way to get experience points and really utilise the open world of the game; you know, passing by landmarks and that sort of thing. Additionally, it was a way for players to change their experience of the game from the detective to doing some chases and some shoot-outs. The overarching story is quite linear, yes, but there is deviation within a case that allows the players to change how they're doing it, like the cases which have different endings depending on where you go and what you choose. I think one of the things people don't realise so much is, because we've made the conversation system quite subtle, not throwing up dialog boxes here and there, you do actually branch things, and you do get awarded for getting things right. But when you get something wrong, it's not advertised, so the experience, while linear in terms of the story--you can have a different experience playing through it. So that gives players the whole, 'How did you do this?' and 'I did it this way.'"

The long and winding path to shipping L.A. Noire has finally come to an end, but after such an exhaustive process, is the squad ready to do it all over again? Watch our interview with Team Bondi studio founder Brendan McNamara to find out more on the company's future for DLC, its plans to move to full-body scanning, and what it will be working on next. If you haven't already finished the game, be warned; the interview does contain some major storyline spoilers.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation