Five ways games can make you cry

GDC 2010: Ubisoft Montreal's Richard Rouse III explains how reminiscence, amplification through abstraction, transformation, loss, and nostalgia can make games emotionally poignant.

(SPOILER WARNING: This article contains spoilers about the endings of Fallout 3, BioShock, Portal, and several films and television shows. Proceed at your own risk.)

Who Was There: Richard Rouse III, narrative director of Assassin's Creed II developer Ubisoft Montreal.

What They Talked About: Rouse began his 2010 Game Developers Conference presentation by saying that the debate on whether or not games can make you cry isn't new. In fact, Steve Meretzky, creator of the 1984 text game based on the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy books, told him "That topic is so 1993." However, with games becoming more and more accepted as an art form, Rouse laid out some approaches used in other media that he thinks can make games more emotionally resonant.

First off, Rouse pointed out that many other kinds of media make people cry. (He himself opened up the waterworks at the end of the movie Titanic and during a Rush concert "because they are so damn awesome.") One of the ways this is done is through reminiscence, or the process of making the viewers or listeners look back at their life. As an example, he played the video for Johnny Cash's cover of Nine Inch Nails' "Hurt," which showed the aged singer--not long before his death--intercut with footage of him as a young man in the 1950s and 1960s. "That was your life," is how Rouse summarized it.

This common technique is used in films like Titanic and in games such as the Sims, which scrapbooks key moments in a sim's life and saves them for the player to watch later. The prime example he showed was the ending cinematic of Fallout 3, in which the "Lone Wanderer" protagonist is shown his accomplishments in the game via a sepia-toned photo montage.

In this particular instance, Rouse ran a clip of the ending associated with very high Karma, in which the player is shown the faces of the people he has saved and is reminded of the values handed down to him by his in-game father. "It shows you what you've accomplished over 40 hours, and adds to the fact that the end of a game is a sad time, since you don't get to play anymore," said Rouse. (He did not mention the five Fallout 3 expansion packs that would follow in the coming months.)

The second method of narrative tearjerking is "amplification through abstraction." To illustrate this point, he showed a clip from the anime drama Grave of the Fireflies, which chronicles the struggles of a young boy and his younger sister in Japan at the end of World War II.

Orphaned and shunned by extended family members, the starving pair take refuge in a mine shaft before the boy goes out to seek food. When he returns, he finds his delusional sister dying, having eaten dirt clumps and marbles thinking they were rice balls and candies.

Rouse said that if the scene had featured real actors, it might have been unbearable or cheesy. However, since it was an anime, the young girl is abstracted. She is a template for viewers to project images of young girls in their lives onto the experience, making the emotional punch more powerful.

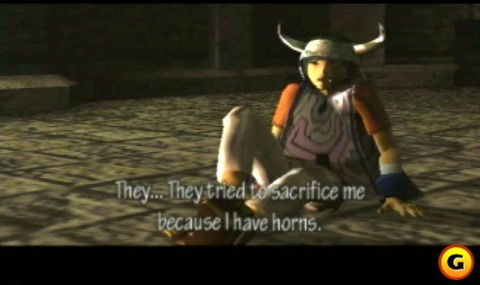

For Rouse, games that have done this include the text-only Planetfall, in which the character Floyd sacrifices himself to save the player, and the very anime-like ICO. He showed a clip from the "art game" Passage, in which two tiny characters walk down a passageway, not knowing what lies ahead.

Method three for evoking eye-sopping emotion in games is transformation. "The weak shall inherit [the Earth]," says Rouse, before showing the film paradigm of this concept, It's a Wonderful Life. The Frank Capra classic centers on George Bailey, who stays at an unprofitable small-town savings and loan because he feels the need to help others buy homes. Discouraged, he ponders suicide and is then shown that his life touched others. Showing the film's finale, Rouse said this is the classic example of people crying at a narrative's happiest part, not its saddest.

In games, the example Rouse offered was the finale of BioShock--if you chose to rescue rather than harvest the Little Sisters. He showed a clip that has the game's penultimate scene, when an ADAM-mutated Frank Fontaine is bum-rushed by all the Little Sisters the player has saved. As the freakish hulk collapses while being pierced by dozens of viciously long hypodermic needles, Rouse deadpans it wasn't quite It's a Wonderful Life.

Rouse's fourth method for evoking tears in games is the concept of loss, or "you don't know what you've got until it's gone." His filmic example of that was a scene from director F.W. Murnau's silent film Sunrise, in which an alluring woman from the city convinces a small-town local to kill his wife. When it comes time to do the deed on his rowboat, he finds he can't go through with it. Later, though, his wife is knocked overboard and presumed lost. Furious, he goes to kill the city woman--only to learn his wife is still alive, making for a happy, but tear-filled, ending.

In games, Rouse held up Portal as an example of the "you don't know what you've got until it's gone" technique. He said even though the GLaDOS computer spends much of the game trying to kill the player, the deranged AI is the player's only companion throughout the game. So when it comes time to destroy its computer core, players are left somewhat saddened since they effectively lost a friend. That feeling diminishes, though, when the player discovers that GLaDOS is still alive. He joked, "Oh, that's great! She's back and can try and kill you some more!"

That said, Rouse said the only time he personally cried was because of a game one might not expect. He then showed pictures of himself and his young daughter playing Nintendogs on a DS. Due to his daughter's tender age, Rouse had spent hours showing her how to care for their Nintendog. Confident she could handle caring for the virtual pet on her own, he left for a weeklong business trip--only to be told via phone by his wife that the dog had disappeared.

Distraught, he came home and discovered the dog was indeed gone. Despondent, he said he actually went through the five phases of grief--until, one day, the dog reappeared with a gift in its mouth. Rouse explained that Nintendo had put a mechanic into the game that made a dog vanish if it wasn't cared for properly but that made the dog eventually return to give the player a second chance. He said that was a perfect--and powerful--example of a game maker using the loss technique.

Rouse's fifth and final method to make gamers cry is nostalgia. To illustrate this point, he showed a scene from the season finale of the first episode of the television series Mad Men. In the scene, the philandering advertising executive Don Draper makes a powerful pitch for a campaign for Kodak's then-new slide projector. While showing photos of his own family during happier times, he talks about how "in Greek, nostalgia literally means the pain from an old wound." He names the slide projector the Carousel, since it "lets us see the world as a child sees it."

In Rouse's opinion, games do the same thing as the Carousel. Whereas kids like to play dress-up, games let teens and adults don a different guise and enter a similar fantasy world. This can have a powerful effect in single-player, he explained, again holding up ICO as an example of emotionally poignant game-making.

Rouse concluded by saying that massively multiplayer online games can also bring about a sense of nostalgia the same way real life does. That's because increasingly, people are making friends while playing MMOGs. Online play also helps sustain friendships between friends separated by distance when one friend moves away.

Quote: "What do you mean, 'Fu-Fu's gone'!?" --A distraught Rouse, upon being informed by his wife that his favorite Nintendog had disappeared.

Takeaway: "Games let people live lives we never had and lets us think about our lives in a new way," said Rouse.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation