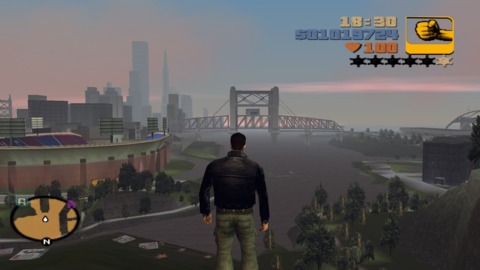

Dan Houser Opens Up About Grand Theft Auto III

Longtime series writer discusses GTA III's ongoing legacy, why he's not concerned with public outcries, and how "no one gave a crap" about the game at E3 2001.

The name Dan Houser might not ring a bell for every Grand Theft Auto fan, but the English-born game developer has been a critical part of the franchise's success over the years. Among his notable contributions to the franchise is co-writing Grand Theft Auto III, the title that pushed the series into the mainstream spotlight and left a substantial mark on the next decade of game development. As we approach GTA III's 10-year anniversary, GameSpot recently sat down with Houser to get his opinion on the landmark action game's legacy, how the series has changed in the past decade, and some of the struggles the development team faced early on.

GS: Was there a particular point in time when you realized this was a game that people would still be talking about a decade down the road?

DH: During development, we obviously had no idea that it would go for 10 years or that it would be as successful as it was because you could never really hope for that level of success. Even the developer sort of fractured through the making of it. People didn't stay with us early on, because we were moving DMA down to Edinburgh and turning them into what would become Rockstar North. Some of those guys were like, "This could never work for reasons X, Y, and Z."

"…you could never really hope for that level of success."About a year out--maybe 10 months or so--we first had the city, the cars, some of the weapons, and an enormous reservoir of problems that we hadn't figured out yet. We were like, "If this could get to where we think it should get to, this is going to be amazing. Now how the hell do we solve those other problems?" And then, the early part of showing people the game--including E3 2001--was disconcerting because it was incredibly underwhelming. Because we thought it could be magical. Not the Holy Grail, but this thing that was 3D but open and expansive, combining elements of hardcore action, driving, adventuring--all these genres. Very cinematic and story-driven gameplay, this experience that's really unlike anything you've seen before. And people were scratching their heads around it! We were all, "Are we wrong?"

There was enormous excitement around a few other games coming that fall. We went to E3 and everyone was obsessed by State of Emergency, and no one gave a crap really about GTA III. State of Emergency we thought was interesting, but not without its flaws--some of which never got resolved. But GTA III was already running, and we thought, "This is amazing!" But E3, I think, isn't the best place to show a game anyway, and that's definitely become solidified in our thinking since then.

The second half of 2001 changed people's perspective with some success. But still, it didn't really happen until consumers got their hands on it. I definitely think we were convinced the game was going to be pretty successful and we would make another one. Assuming Take Two didn't go bust because it was under enormous pressure. We'd begun to realize there was something really interesting in this kind of game. All of 2001 we sort of realized, hey, there's something really interesting here--are people going to see it? But we were very passionate about it from that point on.

GS: Can you describe your writing process for GTA III? How has it evolved since then, with recent games like Red Dead Redemption?

DH: I'm trying to think. Is there such a thing as a process? Are we that organized? I don't know if we are.

GS: Would you call it a lack of process back then?

DH: No, it's sort of similar in some ways. We don't necessarily separate the story and the design--they're kind of the same thing. We use the story to expose the mechanics, and we use the mechanics to tell the story. So it should feel very integrated. The way we organize the games is by missions, and the way we organize missions is by story. So there isn't really a big difference.

"We went to E3 and everyone was obsessed by State of Emergency, and no one gave a crap really about GTA III."To begin with we were like, this is going to be easy! We'll just take GTA--which was probably a stronger game than GTA 2 vibe-wise--fix the bits we didn't like, make it in 3D, and we're done. Which was probably the most naive idea we've ever had. Something we've learned over the years is that the ideas aren't the difficult bit; the difficult bit is the implementation.

One of the things that GTA 2 had become bogged down with was this idea of nonlinearity. There was no story. With GTA III, we came to terms with the idea that what nonlinearity meant was choice. The skill was combining the strengths of freedom of choice with the strengths of narrative. On some levels they're diametrically opposed, so the skill was trying to figure out a structure to everything that would allow you to reconcile as best you could some element of narrative while still giving the players constant choice.

A good story is one that moves you through the experience well. Yes, you want clever plots and clever twists and clever this, that, and the other. For a game like this, we needed something that moved you around the map well and kept you engaged and is a constant series of mini-stories. Each mission is like its own short story, and then you need this overarching story that the player doesn't lose track of. You don't leave too many things unclosed, you don't leave too many characters hanging there, you don't slaughter absolutely everyone, but you do get revenge on some people. As much of that stuff as possible.

In doing all these open-world games, we've been learning each time to refine [our storytelling process], change it slightly, and modify it. We've overhauled those processes, but they're not radically changed. They're still in some ways fundamentally the same--the mission structure's kind of fundamentally changed a bunch--but it's evolved on from what it was.

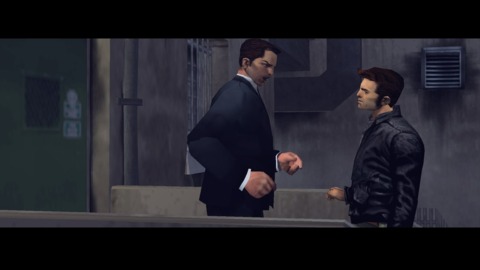

GS: It seems like one of the biggest changes in storytelling is that you guys have moved on from the silent protagonist. Was that change brought about by more technical resources for added characterization, or was it simply a narrative decision?

DH: It was a combination of the two. We were solving so many problems the first time. How would you bring a 3D world to life? How would you make a game that combines these seamless modes? How would you make a story that's both linear and nonlinear at the same time? And I guess we, quite consciously, came to the realization that…how would you make a player speak in an open world? We can't bother. We can't figure that out right now. We didn't even know if the narrative was going to be interesting enough to warrant it. We spent a lot of time on Vice City solving that riddle.

"…GTA 2 had become bogged down with was this idea of nonlinearity."Once we realized that the stories could be and were as interesting as we hoped, we realized the next step was that the protagonist was going to have to speak. Even by the end of III, he wasn't just an everyman, and he had a personality. He just didn't speak! So that was a little bit disingenuous. It ended up feeling like it worked, but it could have been better if he'd spoken. It was a natural progression.

GS: Why has the series shied away from using celebrity voice actors?

DH: Two reasons, one practical. It used to be that we could get a famous actor in for a day or two, or even for a big part four or five days, and do all of the voice work needed. On PS2-era graphics, that gave us decent results. Now we don't really have a difference between our animation process and our voice-overs. When people use the words "voice acting" now, it doesn't really make sense to me. There's no voice acting. There's acting, now. Their movement and their voice are the same thing done at the same time. There is no difference between the two.

By the end of San Andreas, we were getting better results with non-famous actors. One of the actors playing a part stormed out. Not famous, but a minor C- or D-list actor. He stormed out because he didn't like the fact that the character was gay, or in his mind was gay. I liked the guy who'd done the mo-cap [for the character], so we just used him. And we got a brilliant result. He feels a lot more like the movement and the voice. They feel a lot more integrated. Once we moved to high-definition, that became a lot more important.

Another reason is that for the PS2-era games, we were aspiring to something that felt like you were in your own movie or your own TV show. Now we're able to get things that feel a bit beyond that, and having the famous people really distracts you. Now if we have famous people, they tend to be playing themselves.

We're still using top-level actors; they're just not famous ones. We audition them and take a long time figuring out if we've got the right ones, but we feel like we're getting better results for what we're doing. To me, it feels like a lot more alive now than it did then.

GS: So much fuss has been made out of GTA III's morality, but a lot of that was really a result of the player's own doing. Was that brought about because of a conscious decision to reflect the player's actions, or more of an evolution from the content in GTA 2?

DH: It was more of the former. The key idea of the game was that it wasn't about violence; it was about freedom. We thought that was something that games did very well, the idea that you're turning a viewer into an active participant. So give them the freedom of choice over what they do. Like what we were talking about with the story, give them the choice over what they do next. And when you're not in the story and you're in the open-world stuff, you can really choose what you do. Good, bad, and indifferent. Drive around listening to music. They were limited, but there were some minigames. Or you could be as big a sociopath as you see fit, and the game will punish you accordingly. The thing about the game is that, in some ways, it's the exact opposite: you get punished as much as you can punish someone in a game for your actions. And you don't get away with anything!

"By the end of San Andreas, we were getting better results with non-famous actors."Subsequently, as we've developed the games and expanded them, we've tried to improve all of those things. We've certainly tried to improve the story, but we've also tried to improve how the non-story content works and make the space between the two smaller. A variety of content that's not likely to get you arrested, and a variety of content that is. We've tried to develop all areas of that. But we've definitely tried to give players freedom in how they played the game. That was key to what the game was about and is about.

GS: Why do you think it's still a struggle for games to be taken seriously as a vehicle for those mature themes?

DH: I don't know. We kind of do what we do, take the heat for it, and move on. If what we do is wildly pathetic and immature, we'll take the heat for that just the same as if it's fantastic. I suppose partly it's because they're animation. They're mechanical. They're still better at doing physical things than emotional things. Though I think L.A. Noire showed there's a pathway toward doing more diverse content and mechanics in that way.

It's still a young, young medium. I don't think in 1925 or 1930 or whenever movies were the equivalent age to where games are now people were taking movies anywhere near as seriously to where people are taking games right now. You can't expect games to have the same cultural cachet as an established medium because that's not how things work. But that's clearly changed in the past 15 years, and it will continue to change.

There was a real danger when things were being taken to the Supreme Court. That was the thing to take seriously. Everything else is about vanity. It doesn't matter whether we excite some abstract panel of cultural arbiters. What matters to us is do we excite, educate, entertain, amuse, stimulate--or fail to do any of the above--this individual playing our game? That's the person we want to have a relationship with.

GS: Despite the mature themes and the crime movie aesthetic that the game embraced, one of the things that really stands out about GTA III is the sense of humor. Do you think GTA gets enough credit for its satire?

DH: I hope so. I mean, it does with fans of the game. But that's the stuff that comes out slowly. You can have an opinion of it from watching someone play it for five minutes--this is mindless filth or it's brilliant, or any point between the two depending on your sensibilities. But you'd never get [the satire] until you've actually sat and played it for several hours, because that's designed to be a slow release. It's lots of little subtle touches. You're hearing it on the radio, you're hearing the way a pedestrian speaks, you're looking at a billboard--it's quite subtle stuff.

I think amongst fans of the game, some obviously don't like it, but large tracks of them love it. For us, the gangster-ness and the cynicism are intertwined. They're the same thing. The whole thing is meant to be America as if it's the way it's presented in the media. And it's still the case now. It might be done in a slightly more nuanced and different way now, but that's still what the gameworld is supposed to be like--this prism of America as if viewed only through movies and advertising.

"You can't expect games to have the same cultural cachet as an established medium because that's not how things work."Taking out the humor is no more valid than taking out the carjacking. They've both changed over the years, and will continue to change, but they are what the game is. It's this kind of look at America's media culture and criminality as being somehow intertwined. Does it get credit for it? Well, the games are popular, so I think it gets some credit for it.

GS: How do you think the sense of humor and satirical elements of the game were influenced by the studio being in Scotland and your own background as an Englishman? Can you imagine how the game would be different if you were an American writing about American excess?

DH: Well, I have Lazlow who's definitely American and does a lot of [the humor] with me. And he's more cynical about it than I am. Certainly there is an element of, as you say, an outsider's look at America. But a lot of the most cynical stuff is his [laughs], so it's not exclusively that.

Going back to what I was saying before about what the game was trying to be, it wasn't trying to be reality. It was trying to be the reality of a movie world. And Britain's relationship with America is so odd because you consume so much American entertainment. To someone who grew up here it would seem incredibly banal, but it's stuff that seems exotic when you don't live here. It's set in Hollywood, which is amazing and exotic! Or it's set in New York, which is this boiling cauldron of insanity! But of course, when you actually move there you realize it's not that different from Britain and is less insane in many ways. So the whole concept of the game and the conjecture of the game was definitely based in an outsider's view of America, yes.

GS: Why do you think it is that music has become such a huge part of the GTA series since GTA III?

DH: On the most basic level, because we took it very seriously and put a lot of music into the game. We took a lot of care with the songs. We were obsessed with the music. Sam [Houser] and Craig [Conner], who did the music then and still do the music with us, they'll still bicker about every single song on every single station on every single game. It's an enormous labor of love, so I think that's probably one reason.

On a more structural level, because we found a way of doing music that was unique to the game in that the music was entirely environmental. Not only were you given a choice of what you'd listen to, but you were playing these games for so long you were slowly learning the music and falling in love with it. So the great pleasure for us was introducing songs that people hadn't heard of.

"The whole thing is meant to be America as if it's the way it's presented in the media."People might begin by going, "I don't even want to listen to that station! I just want to listen to rock!" The rock station and the contemporary hip-hop station always get hit the most [early on], and over the course of playing the game players begin to discover all these weird bits of music we put in there and fall in love, hopefully, with some of the songs. You can look at some of the songs we've used in the games--you look at them on YouTube and realize people are going, "I first heard this music in GTA!"

GS: Looking back on GTA III now, it essentially created a new genre of games--what you might call the modern sandbox action game.

DH: We prefer the phrase "open-world" game.

GS: Why is that?

DH: We're British. We call it a "sandpit." [Laughs] What do you think the word sandbox means?

GS: Obviously, there's that association with children playing, but to me they're interchangeable. Open-world and sandbox.

DH: To us, it's more sandbox has this idea of throwing things in without any sense of choice over what's going in there, while we were carefully picking features and controlling the experience in a particular way. It wasn't this total freeform experience. We gave the player more freedom, but it was just controlled in another way. That's why we prefer "open-world." It's just more descriptive of what we felt we were doing.

GS: So how would you describe GTA III's legacy in terms of the open-world action game?

"…they'll still bicker about every single song on every single station on every single game."DH: When it turned up on PS2, it created something that felt very radically new. It was this combination of an environment that was full of content that you accessed through geography as much as timeline. And now what seems incredibly obvious but at the time was incredibly progressive, but seamlessness between mechanics or modes. You were driving because you got into a car, not because you entered the driving mode. You were shooting because you pulled out a gun, not because you entered the shooting bit. You can do anything, anywhere, within reason--reason based on logic rather than mechanical limitations, if that makes sense. That's been its biggest legacy.

Games, as a medium, show off space very well. Better than a film can, better than a book can. So we used that as a strength rather than a weakness. That's definitely been a legacy of GTA III. And as you said, it made a genre--whether it's called this or called that doesn't really matter--that's one of the most vibrant genres today. It's a large section of action games. We're doing something totally different with Max Payne 3, so it's not the only kind we think is any good, but it's certainly a kind that we think is very good.

GS: It seems like one of the genres that has embraced this style most wholeheartedly is role-playing games.

DH: Yeah, I think they've become the same thing in some ways. There's a large amount converging. If you look at some of the American RPGs and what we're doing, the differences are a lot smaller now than the similarities. The difference is, we're putting role-playing elements into an action game so we came out of very tight mechanics, and they've maybe come out of more of a role-playing and stat-based system and are trying to impose [action] mechanics on top of that. Whether one approach is better than another, who's to say? But clearly from a consumer standpoint, or a philosophical standpoint, there aren't really radical differences anymore. I don't know if that's a good thing or a problem. I think it probably shows that the direction both have gone in is clearly an interesting one, because they've kind of ended up in a very similar place.

GS: When you were working on the game, did you consider GTA III an RPG?

DH: You know, we took what the genre was and tried to take it down to the most base level. We considered it an open-world action adventure game. We looked at what "open-world" meant and did that. We looked at what "action" meant and did that. And we looked at what "adventure" means--not an adventure game, but what adventure means. We wanted the game to feel like an adventure, and I guess in some ways that's what an RPG is trying to be.

In the core [essence] of a role-playing game, we want you to play the role of being a gangster in this world. We definitely wanted that. By San Andreas we put some very limited role-playing bits in there, and we still kind of include some of those under the hood now, so obviously we find that stuff very interesting.

"If you look at some of the American RPGs and what we're doing, the differences are a lot smaller now than the similarities."We try not to get bogged down in the genre stuff, because then you'll get really obsessed by what you don't do in these genres. But what's the interesting experience? We definitely take from everywhere and try to make an overall experience that's fun and coherent.

GS: Finally, if you could pick one film director to do a Grand Theft Auto III movie, who would it be and why?

DH: We didn't make a GTA movie for a reason, and the choice was ours. We probably could have got most people to do it, but we had no interest in doing it. One of the points about GTA was, it was the first time where if you thought about moving it into cinema, you were condensing it, not expanding it. It wasn't like how do you find all the things you put into the film? It was how do you streamline this into a cinematic experience? That's something where we never figured out the answer to the question. It was something that didn't exist in 50 different media. It was a game property, and that was something to cherish and not be embarrassed by.

So if the question is simply who do we think makes great films or has made great films and would be one that we would be most influenced by? Then, I would probably say--without putting words in other people's mouths--for me it would be Hitchcock, for Sam it would be Sam Peckinpah, and I guess a lot of people at Rockstar would go those two or Scorsese. Those are sort of all our favorite directors.

But no, we never remotely actively pursued a movie. Because we thought in games we could do something that was maybe limited in lots of ways, but in scope and ambition was beyond movies. Games are trying to, hopefully, aspire to do something that movies can't do. That's what's exciting about them. We're not trying to be like the film industry; we're trying to get past the film industry.

GS: Thanks for your time.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation