Black or White: Making Moral Choices in Video Games

Why are moral choices in games so black and white?

You and your three companions step out of the elevator doors to a peaceful scene: an airport lounge milling with unsuspecting bystanders. No one has seen you, or the machine guns. In an instant it’s all over: a shower of bullets, screams, falling bodies, and blood-stained carpet. Your companions have moved on, executing those left alive. What do you do?

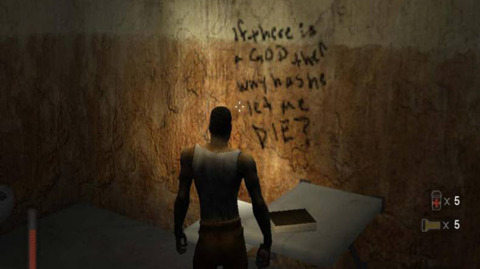

The emergence of morality in video games is arguably one of the most important innovations of the medium to date. Like in the above example from Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, giving players moral choice is a progressive development in games that adds more weight and substance to player decisions, leading to a more immersive and satisfying experience. Whether it’s abstaining from shooting civilians while infiltrating a terrorist cell, saving or harvesting Little Sisters, or holding the fate of the Capital Wasteland’s people in your hands, moral decision making in games is becoming an increasingly popular aspect of game development.

But is it all an illusion?

Morality is not a black-and-white concept. Reality is very seldom as simple as a choice between good and evil; the spectrum of moral behaviours is as complicated and consequential as our emotions. Instead of mirroring this complexity and including moral choices that lead to genuine in-game consequences, video games often do the opposite--they present a watered-down version of moral choice that ultimately results in players having to choose between good or evil: to harvest or not to harvest (BioShock), to be “paragon” or “renegade” (Mass Effect), to kill innocents or to save them (inFamous), to have a halo or devil horns (Fable II).

In this GameSpot AU feature we will look at the problems arising from morality systems in video games, and seek to answer why morality is needed in games, why moral choice is so often just black and white, and what developers can do to change this. In Part One of the feature we’ll speak to philosophers and game theorists and in Part Two we'll speak to developers to find out whether complex moral choices are needed--or wanted---in games and how morality systems can be improved.

Morality 101

In a nutshell, morality refers to the codes of conduct that form the backbone of a society. Generally, morality is concerned with how people should behave rather than how they do behave. Morality can change over time and take on new meaning as people and environments evolve--for example, slavery was once accepted as morally permissible, whereas now it is accepted that enslaving another human being is immoral. In philosophy, morality and ethics go hand in hand: morality pertains to certain rules and codes of conduct while ethics pertains to the application of these rules in society.

Morality as it applies to video games can be thought of in much the same way. Players are most often asked to decide on a morally correct or incorrect course of action. This pertains to in-game behaviour and, in most games, is intended to shift the outcome of the game in one way or another depending on what the player has chosen to do. However, as we will see later, it is most often the case that these in-game choices have little or no bearing whatsoever on the end outcome, resulting in an insincere portrayal of morality. But why should we care? Why do we need morality in games at all, when it’s perfectly obvious that some games function perfectly without it?

Emil Pagliarulo, lead designer for Fallout 3, knows that morality does not play a role in every game. He does, however, believe that if the scope for a moral system is there, it’s up to the developers to make it work.

“If it makes sense to include moral choices, if that’s something central to a game’s themes or gameplay, and it makes the game a more enjoyable experience overall, then morality certainly has a role,” Pagliarulo said. “In Fallout 3, the struggle of people in a post-apocalyptic wasteland lends itself perfectly to a morality component, so for us, it was a must," he said.

“It’s the job of the developers to define their experience for players, and determine exactly where each system fits in. Is the game fun in a hack-everyone’s-limbs-off sort of way, or is it fun in a wow-this-game-made-me-think-and-did-stuff-I-never-expected sort of way?”

For Pagliarulo, the appeal of a morality system is to break the monotony of experiencing the same thing over and over again. He says gamers have come to realise that there isn’t a lot of experimentation or thinking outside the box in the games industry at the moment--for every LittleBigPlanet there are five first-person shooters with the same mechanics, structure, and story. But morality systems shake things up; gamers have to think about their actions and choices and, more importantly, the reasons behind them.

“I think players simply get tired of experiencing the same things over and over and over in games. Frankly, it gets boring. When morality’s involved, the simple act of shooting a bad guy isn’t so simple anymore. You’ve got to ask yourself, 'Well, is he really the bad guy? Was he maybe just trying to defend himself? Should I really be doing this?' So just the act of questioning what you’ve done a thousand times before instantly makes it different, and more interesting, and therefore, in a lot of cases, more fun," he said.

BioWare writer and designer Mike Laidlaw agrees that morality adds depth to games. He says that even when morality has no long-term impact in the game world, a game with a morality system is better than one without it.

“The role of a morality system is a means by which a game can be aware of the way a player is interacting with the in-game world; in some ways it’s a way for players to measure their own progress in a certain way. It’s also a mechanic that lets us realise that these choices have some weight. It helps players understand that the things they’re doing and the choices they’re making have an impact beyond the moment," he said.

“Even if it doesn’t have a long-term effect, it still forces players to think about those moments. I’m not saying that every morality system ever made is the best thing ever. I think in general, anything that makes a game more interactive, whether it’s successful or not, is good. It plays to the strength of the developer and the medium. I can’t defend it in all cases, but when it’s done with a good intent and done as well as it can be I think it makes the player engage with the game on a deeper level.”

Most games portray a dualistic morality system: regardless of context, players end up playing as either ‘good’ or ‘evil’ characters. Some games employ a ‘morality meter’ that promises to keep track of players’ in-game actions and change their experience accordingly. Sadly, this very rarely happens--most games that promise a tailor-made experience according to player choices end up disappointingly consistent and devoid of any real consequences for a player's actions. This results in an experience that feels like it has more depth but very often just has the illusion of depth. So why is morality in games so black and white?

Peter Rauch, a Comparative Media Studies graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, MA, is a veteran gamer: in his own words, he’s been gaming since he was “old enough to stand on a milk crate to reach the joystick at arcades”, and he’s been studying them ever since. His last years at MIT were spent researching morality in games, looking at how moral arguments could be used in games to encourage players to pay attention and provide new ways to think about it in the real world.

“What I’ve found is that video games are a great medium for provoking discussion of moral issues among players who already think a great deal about such things,” Rauch said. “However, most games use a hodge-podge of different moral systems and when these conflict, the result can be bizarre.” Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

Rauch believes a lot of games make use of very simplistic moral ideas, which at times can take players out of the game,though it’s all about how well the morality works in the context of the gameplay.

“Seeing certain options open up and others close off was one of my favourite things about the single-player mode in Star Wars Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II, and the difficulty of maintaining a consistent ethic in The Suffering made my whole experience more intense,” Rauch said. “Fable’s morality system is a train wreck, but even that made it a more memorable experience. Laughing at the fact that eating tofu helped me prepare for cold-blooded murder was probably the one saving grace of that game.”

According to Rauch, people like a little villainy with their heroism, which is why morality in games is becoming so popular. Besides adding an extra layer to the gameplay, morality systems are supposed to allow players to better identify with their characters and to some extent, begin to better understand their choices and actions in the game. But does this actually happen when players are presented with black-and-white moral choices? The problem, according to Rauch, is the limitations of the medium itself.

“In a game, actions only have moral meaning when they're attached to a symbol that plays a role in the storyline. What actions can be performed from that is largely determined by the genre’s conventions. There are certain moral ideas that just aren't going to make sense in certain genres without substantive changes to the game rules, and you're going to have some limitations in any game in which there's one win condition and one loss condition, especially if that loss condition is usually the player's death. Martyrdom is a tough thing to reward in most genres," he said.

"There are creative challenges for game developers to overcome, but this is always risky because video game production is a capital-intensive business. Games are expensive and slow to produce, and the big name titles are expected to subsidise the losses. Investors would much prefer another Halo clone over something new that might fail.”

But that’s not all. According to Rauch, while moral conflicts appear interesting in dramatic situations, the simple fact is that day-to-day moral choices are usually very simple and intuitive in normal circumstances. The trouble is, video games don’t involve normal circumstances, which is partly what makes them so fun and what makes the idea of a moral system so intriguing. So perhaps one of the reasons why in-game morality tends to be so simple is that most people, including game developers and players, think about it in simple terms when presented with the abnormal circumstances of most games.

The question of whether developers should try and mirror real-life moral choices in games is a complex one to answer. This would certainly break the illusion and give players agency, but would it be a successful game? While Rauch is not entirely convinced it would, he still believes developers should experiment with the possibility.

“I think any new gameplay concept, or any new game genre, is a good thing in itself,” Rauch said. “I like games, and I like seeing them change over time. I think developers should make games that mirror real-life moral choices, and games that mirror highly unlikely, super-heroic choices, and games that imagine entirely hypothetical, otherworldly choices. These games might be boring, but I think that games like The Sims and Diner Dash have pretty conclusively shown us that any activity can be fun with the right design.”

The way to do this, according to Rauch, is to start a conversation.

“Designers, players, and especially critics would benefit from having a few long conversations about how people act in certain situations, and whether they ought to act differently. Players need to be allowed to fail once in a while; it would be nice to have some unambiguously bad choices available. Games right now seem to be stuck in a place where the consequences of player actions are entirely predictable, and take effect either immediately or at the very end of the game. Some kind of partial randomisation, or delayed effect, might help to deepen the kind of experiences we could have with games.”

Variety is the Spice of Life

Games like BioShock and inFamous have attracted criticism from gamers who have discussed the morality element of the gameplay for a number of reasons. The most important flaw cited in these discussions is that the morality systems used in these games give the illusion of meaning to a player's actions. For example, killing or saving the Little Sisters in BioShock is promoted as a very weighty and important player decision, when in reality it has little bearing on your character: both paths give you roughly the same amount of ADAM. Similarly, the "morality moments" in inFamous present a very crude and simplistic idea of morality: participating in either the ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ choice doesn’t advance or impact gameplay in any way, other than adding points to a meter and producing differently-coloured lighting attacks. In order for morality to function properly within a game environment, developers need to pay attention to the consequences of in-game actions, making them lead somewhere instead of nowhere and using them to shape and affect narrative and gameplay.

Assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Central Oklahoma Mark Silcox and associate professor of philosophy at Louisiana State University Jon Cogburn have partnered up to write Philosophy Through Video Games (Routledge, 1999), a text that discusses the relationship between philosophy and video games, and looks at how morality systems work within the game environment. The first thing Silcox and Cogburn do in the text is strongly encourage game developers and designers to study different philosophical systems of morals instead of using inchoate intuitions like ‘good’ and ‘bad’.

“If we could do one thing here, we would first require all video game designers to read one of the excellent short introductions to the western philosophical tradition in ethics,” Silcox said. “There are so many fundamental issues on which smart, informed people disagree that it would not be difficult to design games around the kinds of conundrums and tragic choices that lead thoughtful people away from thinking in such black-and-white terms. One thing we can’t stress strongly enough is that great art can’t just always show ‘bad’ acts, which leads to ‘bad’ consequences. Real life isn’t always that way, nor is great art.”

According to the two philosophers, the function of a morality system in a video game is, like all art, to allow people to imaginatively play with compelling possibilities in a safe manner, experiencing what it is like to be a very different person in a very different situation. This works by the portrayal of certain kinds of actions in games that have typical consequences, which players must react to in various ways. However, how to translate this successfully to video games is still being worked out; according to Silcox and Cogburn, players are beginning to demand something above higher scores and more loot for good behaviour.

“Some of Peter Molyneux’s more recent games were going to be something like this, where the behaviour of the character affects the interface in interesting ways, but neither of us has been very moved by the games themselves. Mechanisms like the one in Fable where you can reverse the polarity of a character’s morality just by mooching off to a temple and making a sacrifice to some deity have a horribly trite and arbitrary feel to them," Silcox said.

“We think this might be done better in games like Empire: Total War and the Civilization series. We’re also encouraged by the fascinatingly complicated systems of etiquette that have sprung up around highly social MMORPGs like Second Life and EVE Online. The more that people’s lives as gamers start to blend together with their social interactions in games like these, the more closely what happens in them can be expected to reflect the ethics of our everyday interactions.”

Something that video game developers should steer away from in trying to achieve a more realistic and textured morality system is the temptation to include real-life moral choices. Silcox and Cogburn agree with Rauch that games based on real moral dilemmas just wouldn’t work.

“It is admittedly very difficult to imagine a genuinely fun video game that mirrored the sort of everyday moral choices that most people end up being preoccupied with, e.g. whether to tell off one’s boss, how much to spend on grandma’s birthday gift, or whether to be faithful to your spouse, as opposed to whether or not to nuke eastern Europe or to spray machine gun fire into a crowd of zombies.”

One solution would be to create unpleasant consequences stem from committing morally questionable acts in games, which would heighten the experience of playing and make game narratives seem more vivid and realistic. Silcox and Cogburn believe that the representation of morality in games is more than just a passing trend, and, as games take on a more and more central position in our culture, designers will find a way to fix the existing problems.

“Game designers would be well served by immersing themselves in the debates between adherents of different moral theories in the Western traditions," Silcox said. "Might we dare to imagine a future in which video game designers actually had a place on the very short list of people whom we routinely expect to provide us with real moral wisdom?” Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

In Part One of Black or White: Making Moral Choices in Video Games we looked at why morality is needed in games, and why moral choices are so often limited to either "good" or "evil". In Part Two, we speak to the people who set the rules by which we play, and ask them to weigh in on the debate.

If game developers begin to think seriously about morality in games and start including deeper and more complex systems in the games they create, what impact would this have on players? The 2007 Polish-developed title The Witcher, a PC RPG based on a book series by Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski, is cited by many gamers as a prime example of a game that successfully implements a multi-layered morality system.

The game uses a system of time-delayed consequences, meaning repercussions of moral decisions made in the game do not become immediately apparent. This forces players to think carefully about the choices they make, knowing the consequences won't come into affect until much later in the game. The in-game choices are also carefully constructed to feel realistic rather than fleeting: nothing is marked as either right or wrong, so players may sometimes make an important moral decision without even being aware they've done it. This approach to morality goes beyond the simple black-and-white model, coming much closer to real life decision-making than other games. The game was reviewed favourably for this aspect, with many critics citing the strength of its replay value due to the ability to have a new gameplay experience simply from making different moral decisions.

But could this heightened element of realism in games be used to teach?

Gene Koo, a former fellow at the Berkman Centre for Internet and Society at Harvard University Law School, has studied video games and pro-social learning for a long time. He believes that video games should move past the one-way communication system that simply transmits values to players.

“We want game developers to think more deeply about what it might mean to include moral considerations in a game, and to the extent to which they actually have a pro-social agenda,” Koo said. “We want them to think about how to embody such values in the very system of the game itself and not just its surface trappings.”

Koo believes we’re still in the early phases of exploring how morality can work in the confines of a game environment. This is still a matter of finding the right balance between computational power (i.e. how do you account for the full range of choices that a player might make?) and artistic representation (i.e. how do you make moral choices and consequences feel artistic in a game?).

“It’s not like the bulk of other media have such deep and reflective moral worlds either,” Koo said. “The bulk of our films, TV shows and books feature schlocky, black-and-white moral worlds too. It’s just that because video games are a newer medium, they’re subject to more scrutiny. However, I don’t accept that we are stuck making morally-shallow games because the very nature of video games compels us to.”

While studying how games can teach, Koo recognises that they don’t need to. Just like Portal helps us look at the laws of physics differently without actually teaching us anything about real-world physics, so too can in-game morality help us look at real-world values and behaviours in a new light. Koo feels there’s more weight in video games that offer moral options without the game directly addressing it.

“Choices without in-game consequences are meaningless. This was part of the debate around BioShock. What difference to the game does it make if you rescue the Little Sisters or not? Arguably, you get more goodies for rescuing them--so are you doing the ‘right’ thing for the ‘right’ reasons?”

For Koo, gamess like the Civilization series are more subtle in their deliberations with morality. He says there are consequences to actions in a game, but if you’re playing the game to maximise your score, there’s no particular meaning to making one in-game choice over the other, except on the strategic level.

“For example, Civilization allows you to choose a democratic or a fascist government. Personally, I don’t find it satisfying to treat the entire game as a flat, mechanical system. I’d like to imagine (as the game fiction encourages us to do) that as a player I’m choosing a way of life for millions of my citizens. That, to me, gives the game more weight than a comparable strategy game that ignores those aspects of civilisation.”

Koo has been increasingly looking at multiplayer games as one of the most promising areas for deepening the moral aspects of games. He believes moral and ethical questions are constantly brought up in MMO guilds, using the player’s individual moral intuitions to create gameplay, rather than forcing gamers to encounter the developers’ own notions of what morality is.

“To move forward we need morality to be better integrated into the very system of the game itself. It can’t just be tacked on as an afterthought. The game needs to be built around some set of moral choices. We also need more genres of games. If a game, at its heart, is a shooter, then the deepest moral questions will centre on the action of shooting. You might come up with a range of ways in which shooting or not shooting something becomes a deeply moral decision, but frankly it will feel pretty limiting. Finally, we need a social physics engine for games that allow single-player experiences to have richer, deeper moral dimensions.”

What The Developers Say

While everyone from gamers to academics can weigh in on the debate, only one group of people can change the direction of morality in games. The decision behind what shape a morality system will take in a game is in the hands of game developers, who have the final word on what choices players will make, what consequences these choices will lead to, and what the final outcome of the game will be. As we’ve heard, in some cases a complex and in-depth morality system just won’t work, sometimes because it is unnecessary and sometimes because the game genre doesn’t allow for a deep exploration of morality. However, in the cases where morality systems have tried, and failed, the developers have a lot to answer for.

When Bethesda first looked to acquire the Fallout licence, one of the things that stood out for the publishers was the way the series handled morality. While the game's Karma system tracked players’ good, evil and neutral deeds, there was also a strong sense of moral ambiguity, meaning choices and actions went beyond the simple 'good' or 'evil'. Bethesda found this complexity convincing, and sought to implement a similar morality system in Fallout 3 that, while mechanically different, had the same spirit.

Emil Pagliarulo, lead designer for Fallout 3, says this has less to do with a well-designed morality system, and more to do with the players becoming invested in the game world.

“I’ve always felt that Bethesda’s style of games --typically first-person, with high-detail environments-- lends itself very well to this, simply because the environments are so believable so it’s much easier to get immersed and feel like you’re closer to the world and its characters,” Pagliarulo said.

In Fallout 3, Pagliarulo and his team tried to ensure the morality meter was neither fleeting nor predictable. For example, while players know that stealing from someone’s house when they’re not around will be registered as a morally bad action by the game’s Karma system, there are a lot of situations that are left morally grey on purpose. Pagliarulo says the reason for this is because he didn’t want players to feel like the developers were the ones deciding what was right and what was wrong.

“We wanted players to make their own determinations. It was a real challenge for us to try and balance all this stuff out and to provide players with gameplay that was completely morally grey in some instances while having a Karma system that tracked specific good and bad actions in other instances.” Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

Pagliarulo believes the moral choices in the Fallout games tend to be a bit grander than other games due to the nature of the science-fiction world that, while containing believable characters, has larger-than-life themes and situations. For Pagliarulo, the real question is just how far should a morality system go?

“In Fallout 3 it’s pretty damn clear that by the end of the game, your decisions have had some serious repercussions on the world. This all sort of culminates in the game’s climax, where you hold the fate of the Capital Wasteland’s people in your hands. Do you poison the water, or leave it clean? Do you sacrifice yourself, or talk someone else into doing it? All of those things--which are all tied to the game’s morality--are pretty central to Fallout 3’s themes and gameplay.

“But would a [morality] system that goes beyond what’s been offered in Fallout 3 make a game more enjoyable? I have serious reservations about saying it would. Unless your game is specifically all about morality, I think that would probably be overkill.”

Another series that delved into morality is Fable. The first game in the RPG series was released in 2004 for the Xbox and PC, developed by Lionhead Studios and designed by Peter Molyneux, now the creative director of Microsoft Game Studios in Europe. The game was a commercial success, and was praised for its innovative concept of free will and choose-your-own-adventure-style gameplay. The point of the game was to problem solve and overcome obstacles by being either good or evil, and watching the effects of these decisions take their toll on your hero’s appearance and his interactions with those around him.

While there was no illusion of anything deeper than that, Fable was also criticised for presenting a very limited view of morality. Players did not suffer long from the consequences of their in-game actions, which could easily be reversed, and had little bearing on the outcome.

Molyneux says the decision to base the game around a good versus evil axis came from the idea of wanting to allow players to be who they want to be and give them the freedom to try different things.

“For a player to think “What will happen if I do this?” is something that is unique to video games,” Molyneux said. “I think having the power to influence events in a game is very exciting. As we have experimented with this it has become less about good and evil and more about who you are as a person and what your decisions tell you about yourself.

“We are still experimenting with how to represent these choices to people. For me it is a mixture of giving people straightforward choices but also allowing them to do the unexpected, so that a seemingly straightforward choice such as saving a man’s child can become less straightforward if you opt to kill the person who has asked for your help.”

But despite Molyneux's response, Fable II presented the same arbitrary morality system as its predecessor. This system had worked well with Lionhead’s first project, Black & White--a 2001 PC RTS, which won credit for its sophisticated mechanics and innovative gameplay. However, the Fable games were aiming for something completely different: while Black & White was centred on the conflict between good and evil, placing players in the position of a god and recording their interactions with the world through good or bad actions, the Fable games introduced many more gameplay and story elements, which required a more complex morality system.

“I definitely agree that our first attempts at creating moral systems in games like Fable and Black & White were pretty crude and simplistic with just a good versus evil axis,” Molyneux said. “But in Fable II we added in other axis such as cruelty versus kindness which made it slightly more complex and compelling.

“We are trying to take this still further in Fable III with poverty versus prosperity and greed versus generosity, which means that the game’s morality system, as in real life, is the sum of these parts rather than solely good versus evil. In Christian beliefs there are only Ten Commandments, and we have continued to reinterpret what we believe is good and evil.”

A developer that is no stranger to morality is Canada-based BioWare, well known for its high quality of storytelling and gameplay. Like other developers, BioWare began with a relatively simple morality system. A game like Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic lent itself easily to a black-and-white morality system, tracking player actions and speech in order to determine an affinity for the light or dark side of the Force. Without the Star Wars universe as its backup, BioWare tried to implement a morality system of the same nature in its 2007 console RPG Mass Effect, where the emphasis shied away from pure good versus pure evil and instead focused on dialogue to determine a character’s nature. Despite this, moral choices were still fairly black and white: players would either end up as “Paragon” (if they were good) or “Renegade” (if they were bad), although the two were not judged on the same scale as in previous BioWare titles that incorporated morality.

According to BioWare writer and designer Mike Laidlaw, morality is now seen as an integral part of games with strong stories, which is what BioWare is best known for. For Laidlaw, morality is all about giving developers access to gauge how players are engaging with the game, taking it a step further from the grind of earning experience points.

“When you’re developing a story, and giving it the level of impact that BioWare always strives for, morality is needed,” Laidlaw said. “In Mass Effect, we decided to focus less on hardcore morality and more on an indicator of the way characters behaved. I think that allowed players to feel like they were evolving and growing and making a character that is consistent rather than one that is neutral, good, or bad. We’ve done one better with Dragon Age: Origins, where we’ve stepped completely away from hard morality and focused on the characters and the people around them.”

BioWare changed its approach to morality with Dragon Age: Origins, dropping the arbitrary morality meter and paying more attention to interactions and reactions. According to Laidlaw, each character in the game has his or her own morality that the game takes into account, meaning reactions are more subtle but have deeper consequences.

“For us as developers we can watch and learn how gamers are interacting with morality in the game. I think what we’re seeing is a hunger for more; gamers want to dive into this. It’s something that we developers are slowly refining --how do we do it, how do we pull you into the moment and make you feel like you are more than a spectator?”

Laidlaw believes the answer to bettering morality in games is to pay closer attention to the idea that characters can, and do, exist in their own right.

“It’s got to be about more than just getting to a climactic moment and then pressing A. Evoking emotions and making characters you can empathise with and that feel very real and have real motivations is the key. We’re seeing more and more role-playing mechanics creeping into other genres, which I think is very exciting. As an industry, we need to get more experience in this, get more evocative, and also understand that we don’t have to be hampered by morality when it is not needed.” What are your thoughts on morality in video games? Leave us your comments below!

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation